You don’t have to hang around MIT long to find out that the concept of learn-by-doing is alive and well.

One tangible example is the UROP program (Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program), started in 1969 by the late Prof. Margaret MacVicar, MIT’s first dean of undergraduate education, who acted on a suggestion by Dr. Edwin H. Land, inventor of instant photography (Polaroid), who believed every student should have a faculty mentor, doing research projects at the knee of the master, as he once described it.

Dr. Seymour Papert of the Media Lab furthered the philosophy, taking the theory of constructivism he learned when he studied under Jean Piaget and extending it to the theory of constructionism, by which the learner creates tangible forms (language, tools, toys) to explore and better understand ideas, then shares what is learned with others.

Civic or community journalism is a manifestation of constructionism where practitioners learn by doing and share their explorations.

This is not to say that teachers take a back seat in the education process. Clearly their direction and passion everywhere, not just at MIT, have a lasting impact on learners. Historian David McCullough spoke at a February forum at the Kennedy Library in Boston and singled out teachers as being the most vital influence in a democracy. Pausing to drive home his point, he said, “Attitude is caught, not taught.”

And textbooks continue to be essential in the education scheme, whether on paper or online.

Indeed, community journalism is now reaching the point of maturity where practitioners’ books and handbooks will emerge based on grassroots experience.

In some cases more than ten years of online publishing has been accrued by volunteer and commercial community publishing groups (one of the earliest and still chugging along is the “Melrose Mirror” at http://melrosemirror.media.mit.edu, which will be starting its 15th year in June).

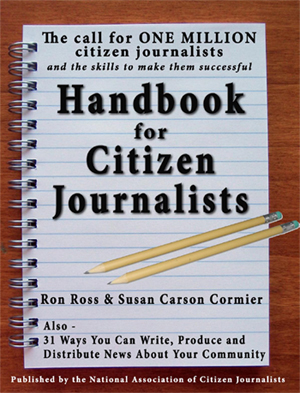

Worthy of note is the new “Handbook for Citizen Journalists”, with Part One written by Ron Ross and Part Two by Susan Carson Cormier, on behalf of the Colorado-based National Association of Citizen Journalists (NACJ).

Worthy of note is the new “Handbook for Citizen Journalists”, with Part One written by Ron Ross and Part Two by Susan Carson Cormier, on behalf of the Colorado-based National Association of Citizen Journalists (NACJ).

It’s half motivational and half tutorial. The motivational aspects were a surprise to me until I discovered that Ross is a former pastor and missionary. A bit of an unorthodox approach, it does confront what in my experience is the biggest barrier to entry for most citizens: Having the confidence to cross the threshold. Once inside the door there’s no turning back. Citizen journalism is fun and energizing.

Cormier has a lot of media experience which is quickly clear in Part Two of the handbook. She also must have learned some teaching pointers from her father, Donald W. Carson, a nationally noted journalism educator at the University of Arizona. She effectively uses the tried-and-true approach: tell the learners what you are going to tell them; tell them; then tell them what you told them.

Handbooks are generally cut and dried, but this one isn’t afraid to stick out its chin, even when addressing its own audience. On the one hand praising the “energetic, self-taught and entrepreneurial types” among citizen journalists, the authors add: “…their work-product is often sub-par, and attracts substantial and often legitimate criticism from professional editors, reporters and consumers.”

They also stick out their chins in describing “accidental journalists” and “advocacy journalism”.

“Accidental journalists,” the handbook says, “are people who are caught unexpectedly in the middle of an event and take photos or videos and upload them to either social networking websites such as Facebook, MySpace or Twitter or news websites such as CNN’s iReport or Fox News’ uReport.”

They then assert: “Accidental journalists are not citizen journalists.”

My view? We could argue that point endlessly and get nowhere. Keep those cameras handy.

Then there is the topic of advocacy journalism. The authors say the following:

Advocacy journalism is a genre of journalism that adopts a viewpoint for the sake of advocating on behalf of a social, political, business or religious purpose. It is journalism with an intentional and transparent bias.

Which do you want to do? Either way, itís okay, but you must decide whether to be an advocate or a dispassionate reporter of news. One is a citizen advocacy journalist; the other is a citizen journalist.

I happen to agree with that but probably would be hard-pressed to find anyone on my side in an academic debate.

Then there is the emphasis on press cards, which NACJ will provide to those who complete its training program:

“The National Association of Citizen Journalists offers its members a way to earn a press ID badge that declares them qualified to ask questions, seek information, observe events, photograph incidents, and interview officials and witnesses.”

For me this has the ring of licensing, a dangerous precedent. Without going down that road (at least not in his article), press badges, except for such situations as covering the President or having access to limited space in a sports press box, have little practical use. How about just a plain old business card that names your organization and provides its URL?

I am part of a community publishing group that decided to make up laminated cards with photos on them for its members about four years ago. Everyone liked the idea; I stuck mine in a drawer. No one ever used theirs.

Nevertheless, the thrust of the NACJ handbook is more pedagogical than preachy, even referring readers to a YouTube site for pointers (youtube.com/reporterscenter), despite having their own YouTube instructional clips (youtube.com/thecitizenjournalist).

Citizen journalists need more exposure to know-how, not so much from professionals as from those who have had grassroots experience. The enthusiasm for learning is there.

My favorite example was a woman who had been part of community website for several months. One night, as she tells the story, she was pounding away at the keyboard when her husband called out from the bedroom:

“Hey, honey. It’s 1:30 a.m., time for bed.”

She was indignant: “He doesn’t understand,” she stammered. “I was writing.”

(More information on the National Association of Citizen Journalists and its book is available at http://www.nacj.us/ Jack Driscoll is an advisor for the Center for the Future of Civic Media at MIT and author of “Couch Potatoes Sprout: The Rise of Online Community Journalism”)