Henry Jenkins gave the closing keynote at the International Communications Association Latin American Conference in Santiago de Chile two weeks ago. His talk was titled “From Participatory Culture to Participatory Politics by Way of Participatory Learning.” This post contains live notes by @schock w/additional links by “mariel.” If you’d like to see Jenkins speak IRL, he’ll be in town this weekend for Futures of Entertainment 6.

What is participation?

Jenkins wants to take us on a trajectory of thinking about what we mean by participation. It’s a term he’s used throughout his career, but also has been shifting in its cultural and academic resonance over time. He’ll link participatory politics, culture, and learning.

#ows

The first slide is from #OWS. Jenkins arrived at Zucotti park, and 100 zombies came off the bus; they decided to join #ows after coming to NYC for a zombie convention. Jenkins thinks Zombies became a central metaphor to #ows: undead corporations that were kept alive by the blood and sweat of the 99%. It’s not a coincidence: other cultural figures could have showed up, but zombies were key. As Jenkins walked around, he also saw fans from other media franchises: Game of Thrones, V for Vendetta masks. He saw people from occupy sesame street, complaing that 99% of cookies went to 1% of monsters. Many people were taking pictures; the figures, much like cosplayers in Tokyo, were there to be photographed. There was a sense of play, spectacle. OWS was a provocation, a desire to change discourse, as much as it was a desire to change politics in the traditional sense. If the goal was to change discourse, the strategy involved producing, remixing, circulating media of all kinds.

Linking conversations about participatory culture and politics

Someone like Stephen Duncombe might say that this was ‘ethical spectacle.’ Jenkins thinks it was a new kind of politics, participatory, linked to participatory democracy. We [media scholars] are finally having conversations with those scholars who write about participatory democracy. Jenkins notes Nico Carpentier’s work on media, participation, and politics.

Participatory Culture

Jenkins shows us his previous definition of participatory culture, from a report his team created for Macarthur: Key elements include low barriers to participation, strong support for sharing, informal mentorship, members who feel that their contributions matter, and who care about others’ participation. Participatory cultures reward participation. ‘Not everyone must participate, but everyone must believe that if they participate it will be valued.’

We can make a distinction between ‘lurkers’ who could participate but don’t, and those who don’t have access to participation.

Jenkins thinks that it’s also important to focus on technology access, and a participation gap that extends across experiences, knowledge, skills, and mentorship. All of these are structured by inequality, and all are determinative of who gets to participate. In other words, underlying the discussion of participatory politics are struggles over democracy and inequality.

Pedagogical implications of cultural participation

When Jenkins arrived at MIT, Seymour Pappert had just written a paper about Samba schools in Brazil as a model for pedagogy. Students kept coming to him with this metaphor. More recently, Jenkins finally has made it to visit these samba schools in Brazil, to see what Pappert was talking about. Jenkins shares a quote from that article, about what it’s like to drop in at a Samba School on a typical Saturday night:

“If you dropped in at a Samba School on a typical Saturday night you would take it for a dance hall. The dominant activity is dancing, with the expected accompaniment of drinking, talking and observing the scene. From time to time the dancing stops and someone sings a lyric or makes a short speech over a very loud P.A. system. You would soon begin to realize that there is more continuity, social cohesion and long term common purpose than amongst transient or even regular dancers in a typical American dance hall…”

Pappert continues, describing the function of the Samba school, which is to prepare people for participation in Carnival. “People come to dance, but are also participating in the choice and elaboration of the theme of the next carnival.”

So the schools create a context that facilitates participation. Pappert argued for the crucial importance of people present in a face to face location, with an openness to all skill levels, from young kids to experienced dancers. All are part of the gathering. In other words, the schools provide a structured context for informal learning. Sometimes the mode of interaction is more didactic, other times more informal, but the point is that anyone can participate.

Pappert wanted to think about how to transfer the Samba School learning style to other areas: mathermatics, computer programming, grammar, etc. This in large part has been the point of Macarthur’s investment in this area.

Jenkins shows an image of NY library digital learning area that is designed to allow this kind of fluid knowledge and skill sharing. He emphasizes that digital media in this space don’t displace print media: print checkouts have increased a great deal. People come together to learn digital skills but also hang out, browse books, and so on.

Another image of a samba school, more recent: women on the sidelines, with cell phones, connecting to their networks. So the Samba school is also a ‘virtual environment.’ On the day Jenkins visited, it was valentines day, so people are dressed in various costumes, messaging friends and loved ones.

A third image: ‘participation police’ who march through the crowd dressed as authorities, looking for people who are not dancing. Jenkins got nervous since he’s not a good dancer… but they gave him a colorful shirt, which allowed him to participate without needing a high skill level 🙂

Participatory Culture is Latin American

So ultimately, what draws Jenkins back to Brazil is the fusion of folk traditions and emerging digital media. Mass media in the North was (in theory) displacing folk cultures, while in Latin America, perhaps less so, since there was more hybridity.

He shows a slide with stills of YT videos created by youth from different favelas, who can connect virtually in ways they can’t physically. Melissa Brough is looking at hip hop activism in NYC, and mediated spaces that serve a similar function.

Next: a slide of Mardi Gras Indians. George Lipsitz talks about Mardi Gras in NOLA as a reflection of “resource poor, network rich” African American communities. Lipsitz: these networks were profoundly disrupted by Katrina. Social networks help people maintain community; Katrina damaged that support system.

Jenkins shows a slide with the ‘4 cs’ of participatory culture: connect, circulate, create, collaborate. Of course, these flow into each other and can’t be isolated.

Guy Fawkes Masks and #OWS

Jenkins shows a line drawing of the Guy Fawkes movement, which tried to blow up Parliament. The state tried to make it a bogeyman. By the 18th-19th century, popular movements reappropriated GF for protest. Then, Alan Moore wrote V for Vendetta, the comic series that critiqued Thatcher regime. The film version is produced in the early years of Bush Admin, and widely read in the US as a critique of post 911, patriot act america. On YouTube, there are endless mashups and remixes incorporating Bush, Blair, and other actors in the war on terror. The subtext becomes prominent in these.

The next step is the move to 4chan. Henry provides a bit of an overview of the history of 4chan. Whitney Philips of U Oregon just wrote a diss about 4chan as digestive process: consume everything, and produce poop for the rest of the internet. 4chan experimented with Joker imagery from Dark Knight Returns. Joker Obama “Why so Socialist?” got picked up by the Tea Party and widely circulated.

Simultaneously, Anonymous comes out of 4chan, and anons use the Guy Fawkes mask to protest the Church of Scientology. When #ows comes along, the GF mask has become a current symbol of protest; occupiers appropriate the mask. There’s then pushback: since WB has rights to the guy fawkes mask, every purchase of the mask supports one of America’s largest media congolmerates. This is a rich instance of the process by which Cultural symbols get appropriated and transformed through processes of participatory politics.

[sc note: for more on this topic, take a look at Molly Sauter’s article on Guy Fawkes Mask-ology]Circulation vs. Distribution

Henry’s next book includes a differentiation between circulation and distribution. Distribution is what Warner Brothers does. Circulation is what networks do, as they take and share media content, and move it from one place to another. Of course, circulation is partly determined by distribution, but it also includes unauthorized distribution. Jenkins uses ‘unauthorized’ rather than ‘pirate’ in order to avoid debates about morality and legality. Although, he argues that rights holders also benefit enormously if they lower the cost of transmission by taking advantage of grassroots circulation.

Pepper Spray Cop

Next example is Pepper Spray Cop meme. He describes the background of the pepper spray event on Saturday; by Monday there were hundreds of mash ups; Pepper Spray Cop became an icon of #ows. Remix and circulation.

Binders of Women

This week, there’s been an even faster turnaround. On CNN, after the debate, commentators didn’t even mention this line. On twitter, within 20 seconds, it had begun. bindersofwomen.org was registered, @romneysbinder existed, and thousands of mashups were produced overnight. Yesterday, Obama used the phrase “Romnesia,” and within 24 hours there were many mashups being circulated.

Henry described these processes in Convergence Culture as the equivalent of political cartoons. This is a wider use of that approach by grassroots communities.

The Cure for Viral Media

The news media would describe this as “viral media.” Jenkins loathes this phrase: we’ve fought for 30 years over the agency/structure debate; ‘viral’ throws agency out the window.

Neal Stephenson produced the ‘viral media’ meme in Snow Crash: irrational, self replicating information; we’re hosts of information we don’t control. Henry thinks this completely strips away the social and political agency of those who participate in political remix. People choose to make, pass on, circulate these kind of texts; if we stay with a ‘viral’ metaphor we don’t ask important questions about agency, motive, and so on.

Kony2012

Just as Spreadable Media went to press, #Kony2012 happened. Henry asks the audience who knows about it; half raise their hands. He notes that internet culture travels through certain circuits, may not be known beyond subcommunities, although they are massive.

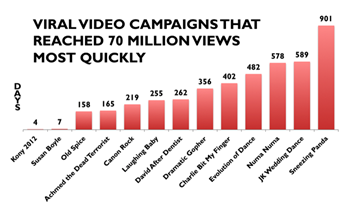

Jenkins now summarizes the goals of Kony2012. Invisible Children thought they’d reach .5 million viewers, eventually. Instead, it blew up rapidly. He shows the bar chart “Viral Video Campaigns that reached 70 million views most quickly:”

Kony2012 took 4 days to reach 70 million viewers. You could add together the top box office from Hollywood and the most popular TV series at the time, and you don’t get to 70 million.

IC was unprepared for the level of coverage they got. HJ isn’t saying he supports their message – there are many valid criticisms. But the rapid sucess overwhelmed IC, and produced the nervous breakdown of one of the organizational leaders.

Next he shows SocialFlow (gilad lotan) visualization of Tweets about #kony2012

This graphic is from this post: http://blog.socialflow.com/post/7120244932/data-viz-kony2012-see-how-invisible-networks-helped-a-campaign-capture-the-worlds-attention.

What it shows us is that the drivers of circulation of the video were from much smaller towns – Dayton, Ohio, Birmingham, Alabama. Circulation may empower communities that were off the cultural radar before. Jenkins shows a picture from Lucerne, Switzerland, of a hanging banner that reads Kony2012. He notes that the Ugandan president responded.

Of course, there was the Slacktivism critique: “Watch 30 minute vieo on internet –> become social activist” image macro:

].

].

The second video IC released, was watched by 2 million viewers. This seems small compared to 70 million; but it’s much greater than IC’s original goal of reaching .5 million. Any PR firm would say this is a massive success.

Macarthur Youth and Participatory Politics network

Henry is working with a team of grad students who have been doing ethnographies of innovative groups. They were already familiar w/IC. He wants to highlight some additional examples. For example, the Harry Potter Alliance uses the storyworld of HP to mobilize fans around the concept “What Would Dumbledore Do.” They try to apply ethics from the HP world to real world activism. Currently, fan activists are fighting to get Warner Brothers to use fair trade chocolate.

These groups bridge between participatory culture, participatory politcs, and institutional politics. There’s a network effect: interest driven networks and friendship driven networks are linked through overarching metaphors and structures, identify causes and issues, model forms of activism, and broker relationships to other, existing organizations. HPA links to NGOs, foundations, labor groups, etc.

None of this looks like Gladwell’s ‘twitter revolution.’ Gladwell compares the civil rights movement in the 1960s with a technology, twitter. To do that, we’d have to compare the use of telephones by the civil rights movement to the use of twitter today. We’d never say ‘the telephone was the essence of the civil rights movement.” The same would be true today. Twitter, YT, mashups, are all tools, used in a broader context.

We see this in Arely Zimmerman’s work on the DREAM activists. He shows a still from Coming Out as Undocumented on YouTube: a risky strategy, in the context of an Obama administration that has deported more people than the Bush administration.

[sc note: here’s a link to my presentation on this topic at the same conference in Santiago: http://prezi.com/user/schock – http://prezi.com/m7fwn46a6s1n/dreaming-out-loud-transmedia-activism-by-undocumented-youth/ ]DREAMers are linking civil rights tactics with new media tools, livestreams, YT, etc.

Closing

Heny ends with a few final thoughts, then opens it up for Q&A.

How do we move from information to meaningful action, and avoid the critique “Kony2012: proving that 99% of youtubers believe exactly what a video tells them?”

How do we move from anecdotes to more systematic knowledge? Macarthur has done a national study of youth, available for download here: Youth and Participatory Politics: a National Survey.

New forms of media literacy are vital: we have to help people gain skills of critical reception. DREAMers know very well that they’ll be attacked online. IC wasn’t prepared for the attacks. So these are important skills that have to be fostered.

Q&A

Carolina Avila de Ecuador: My line of interest is in politics. In Ecuador movements and parties are both strong. But to talk about spontaneous organizations, they have to be organized. There’s a situation of student movements: how can movements of this type deal with the population that says “you are no longer what you were before, you have to deal with t

Henry: I’ve discussed the adhocracy of fan communities. Informal networks, that create fan fic, fan vids, very speedy process. HPA begins to organize that process, and link it to more established organizations. You have to demo credibility at that moment of transition. There’s a long history of outside agitators coming in to fan cultures. Andrew Slack has to prove he’s a HP fan. So far, our case studies haven’t really seen a full on movement. You might say DREAMers are close to being a movement. We’re skeptical of big organizations. Our case studies don’t take us to the point you’re describing. It’s one thing for women to quickly rally and put up a bindersofwomen tumblr, or mansplaining Paul Ryan. It’d not clear how these translate to Get Out the Vote, but it does create a counterdiscourse.

sc: what if we start from social movement media practices? Where do we start looking for participatory politics?

Henry: there are many teams who are doing this work through different lenses. [He name checks a series that I couldn’t capture quickly enough].

Henry’s team is ethnographic. They are looking at DREAM activists, libertarians, etc. They found that DREAMers have appropriated Superman, for example, because superman renounced his citizenship. Right wing got mad. DREAMers said ‘when was Superman a citizen? he arrives undocumented, is adopted by an Anglo familiy, etc.’ DREAmers aren’t all comic book fans, but some were. My sense is: yes. If you look at any movement today, it will follow some of these tactics. We did a special issue of transformative works and cultures on fan activism. [ http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/issue/view/12 ]

There’s something about defining your id as a fan activist, appropriation of pop culture, that’s different than volunteerism that college students do for a line on their resume. There’s something powerful about affective identification with a fan community.

Q: Kiara Sáez universidad de chile. Would like to ask, in regard with the dimension of education, communication, and participatory politics in samba schools in Brazil: Do you, in your theoretical framework, look at latin american authors who have approached this in the 1970s? Paolo Freire, Beltran, other authors who maybe intersect w/popular culture while focusing more on development. They understood the fundamental role of popular communication in the social.

HJ: I forgot my last slide! [it’s a giant picture of Paolo Freire ] [audience laughs]. Freire’s work is fundamental for understanding participation in education. It’s been less visible in the DML network than it should be, partly because Freire’s language is overtly Marxist, and teachers and librarians struggle with how to apply it. But I’ve been reading his work closely. Quote: “Education … as an instrument .. to facilitate integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about confirmity, or it becomes the practices of Freedom…”

Q: Patricia Peña from uC: what is the challnege when we talk about a culture of play? Learning that goes further than the formal? How do you manage the ludic, and integrate it into eudcation?

HJ: The Macarthur whitepaper describes the implications of participatory culture for education. We described 11 core competencies that schools should support. The ludic is key to that. We know call our whole project PLAY, and it’s designed to create a ludic climate in the classroom at all levels. We have whitepapers coming out on my blog. The 4 cs will also come out shortly. I’m very focused on this.

I also want to distinguish, following Nico Carpentier, between participation through the media and participatry media. YT is not a democratic institution. But, a group like the DREAMers or OWS can effectively communicate through YT. Our team has monitored Twitter and YT; there are more than 10,000 Ows related videos. This commercially owned side was used as a distribution channel for their content. This is different than, say, Fox News. Both are corporate controlled, but Occupiers can’t ciruclate things through Fox.

We need to distinguish between a participatory movement, like occupy, a channel, like YT, and a broadcast network that makes it difficult for anyone to participate. On the other side: fandom, that poaches text from broadcast to make it participatory. I’m trying to hold on to my deep believe in agency.

Q: Silvia Pellegrini, PUChile. We’re talking lately here about mobilizations. You’ve described a new form of politics. Still, the participation we’ve seen can be good, or have problems. We need a new literacy to enter, in a competent form, to this culture. My question: is a new type of literacy necessary, that goes further than our current system? Second question: what can we do in that direction.

HJ: Participatory culture isn’t necessarily more civil. We encounter racism, misgyny, homophobia, overtly. Existing political institutions have checks on these, which grassroots groups don’t necessarily have. We’re seeing hostile, destructive, reactionary uses of these tools, for example around immigration. this is not the end battle. We need to build the capacity for everyone to participate, and also move towards better, shared ends. Participatory doesn’t necessarily mean democratic, or progressive. Ethan Zuckerman has the Cute Cat Theory: any tech that lets us exchange cute cats can help us bring down a governemnt. I would add: any platform that lets us post immigrant rights videos also will be used to post anti-immigrant videos. Fiske says; technologies are platforms for battles. Sites of struggle.

In our framework, negotation is a core skill. It’s the ability to move between communities. It’s a central theme of our work around literature, in a book called reading and participatory culture: remixing moby dick. It will have a digital book developed by annenberg innovation lab. How do we use fiction to talk about norms, civility across communities, etc. It’s a step in the right direction, but only a step towards diversity as we foster more participatory culture.

{APPLAUSE & END}