“If I have to leave my apartment and go to a shelter, will my kids be able to go to the same school?”

“If I am undocumented, can I report my wife for verbal and physical abuse? She told me if I call the police they will arrest me because I am living in the country Illegally.”

“Why are there not enough resources to help people in trouble?”

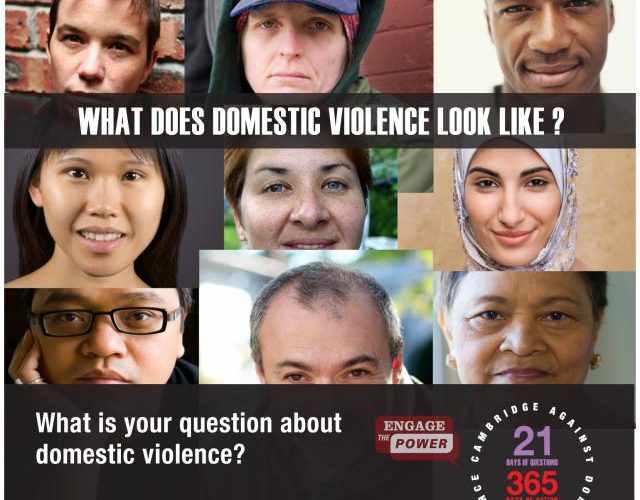

The above questions were all submitted as part of the 21 Days of Questions, 365 Days of Action domestic violence campaign.

On October 17th, 2012, the City of Cambridge launched an innovative public awareness campaign against domestic violence. Through resident organizing, cultural events, discussion groups, public service announcements, social media, drop boxes, tabling, flyers, and billboards, the campaign encouraged Cambridge residents and community members to ask questions they had about the issue of domestic violence. Aside from submitting hand-written questions to ambassadors of the campaign, people could also text, e-mail, or phone in their questions using vojo.co, a micro-blogging platform. The hope in using this type of technology was to capture more questions and give people the opportunity to submit in a way that was comfortable to them. Members of the core planning team manually inputted the questions on to the vojo site, which were submitted on hand-written cards.

There are two especially novel components to the 21 Days of Questions, 365 Days of Action campaign: 1) It uses technology to actually engage constituents in domestic violence problem-solving and 2) Its aim is to involve those who do not normally think about domestic violence in the movement. This research presents a case study of the 21 Days of Questions, 365 Days of Action. Because this effort has been sixteen years in the making and is a continuing process, the study focuses specifically on the time between the campaign launch on October 17th and the question review event on November 29th. Through participant observation and key-informant interviews with campaign managers, I was able to track the outcomes of critical events, gain insights about the process thus far and document hopes for moving forward.

“Even if people don’t engage with [domestic violence] normally, they still have questions – that was what was so fascinating about the campaign,” explained Emily Shield (2012), the Program Coordinator at the Cambridge Commission on the Status of Women. The format of this social movement campaign was especially interesting because it spurred reflection before it pointed to a solution. “The special thing about this campaign is that it does not critique, judge, or ever suggest short-term action. It takes a deeper look at violence. What is it and what are the underlying issues. How do we really interrupt the sources of violence,” said Jacqui Lindsey of Engage the Power, the organization that created and facilitated question campaigns.

Successes of the campaign are listed below:

– It effectively created a lot of buzz in the community about a topic that is usually embarrassing or difficult for people to discuss or acknowledge;

– For the first time, very different types of people were talking about the domestic violence movement in Cambridge;

– The quality of questions was amazing. They were emotional, deep, and strategic. The questions pointed to a lot of different places and paths that need to be further explored to begin solving the domestic violence problem;

– The design and visual branding of the campaign was excellent and provocative; “When people saw a poster or sign, it seemed they were already familiar with the campaign, which means our public relations efforts were effective (Serra Interview, 2012).”

– At events, campaign ambassadors gave people whiteboards to write their question, and then photographed each person holding the whiteboard with their hand-written question. The photo displays of this through vojo.co really helped show how domestic violence is an issue that affects a very diverse group of people. It put a face to a question, which makes the question even more powerful.

However, challenges exsisted as well:

“What happens when you ask people to submit questions about domestic violence? People start telling you their stories. And all these people are told about services available to them, but there are actually not enough services for everyone. When I was collecting questions with people in the street, I was having 30-minute conversations with people who either experienced some form of abuse or knew someone who did. We did have a resource sheet that had information about domestic violence with a whole list of services and how to access them,” explained Ester Serra, a Domestiv Violence Advocate from Transition House (Serra Interview, 2012). Many of the questions collected during the campaign had a sense of urgency to them. They were from people who were in trouble in that moment and needed help immediately.

When ambassadors were out in the field collecting questions, it was not always easy to convince people to use technology to submit via vojo. Over 1000 questions were collected, but a little less than half were contributed through vojo directly. “The method that got the most question was the hand-written cards. “At the mall, we put people’s hand-written cards up on a bulletin display. Because we were trying to reach out to everyone at places like the mall and in Harvard Square, people wanted to write the question and see it go up on the wall. There was no computer or digital exhibit to show the vojo.co site, which may have encouraged people to submit electronically. The only place where people could see their question contribution right away was at the launch event, and this made people want to contribute digitally.” (Serra Interview, 2012). In general, if the option to write questions on the spot was present, that is what most people would do because it just seemed easier.

On January 16th, 2013, the campaign is hosting a public community event to begin formulation plans of action around questions, which have been grouped into similar themes.

It would be very valuable to follow-up on this campaign in one year and evaluate if 21 days of questions actually led to 365 days of action. I would also like to do more analysis on all the questions collected and learn more about who submitted, from where, what types of questions, and using what type of format. Collecting questions allows us to shape an agenda, but finding trends and patterns in who, what, where, where, and why would allow us to understand the problems on the agenda better.

Also, I am interested in better understanding why people submitted questions. “If you see the price of the MBTA going up and a poster or someone asks you to text your questions or comments about it, you will do it immediately. You do not need to trust who is asking you because the issue affects you directly and you see how. With something like domestic violence, people think it does not affect them and so they are not necessarily ready to submit a question. And for others they actually know someone who experienced it or were abused themselves and so it is too personal. You need to built trust with the ambassador to get that question,” explained Ester Lerra when I asked how the issue of domestic violence affected participation rates in the campaign. In a macro sense, it seems the technology to get the question only works when paired with face to face interaction.

Because of the scope and timeline of this study, I could not adequately explore what compelled people to submit a question. However, when I asked my interviewees and others at meetings this question, the sentiment was largely the same: “I wanted to be part of something bigger.”

You can read the full case-study here.