This is a final project update which Sayamindu Dasgupta and I have been working on.

For our Intro to Civic Media final project, we are exploring the ways in which young people are expressing their civic engagement through the interactive media they’ve created and shared in the Scratch Online Community. One of our research questions asks: “When young people use a media creation and sharing community to engage in civic discourse and expression with their community and their peers, what does that look like?”

Below we describe a few examples of civic engagement that occur on the site. We tried to organize them between two categories: issues related to the world beyond Scratch and issues within the Scratch community. For our final project, we will continue to explore such cases, but we may choose to focus on a related few cases to keep our project within a reasonable scope.

Engagement within Local and Global Communities

Scratch members have created projects to connect with issues within their communities, such as current politics. Members may also try to connect issues and events happening in the rest of the world, such as during times of crises. When a Scratch member creates and shares a project or posts a comment on the Scratch Online Community, they can connect with members from around the world. Currently over 50% of the website visits come from countries beyond the United States.

Political Activism

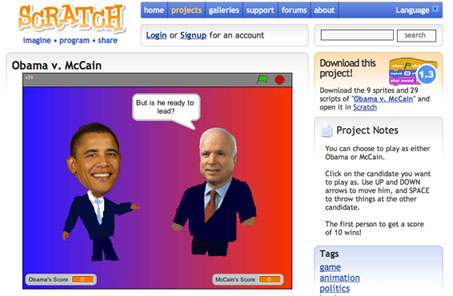

The 2008 United States presidential elections served as a topic for a number of Scratch projects during that time period. The projects differed in approach widely, ranging from interactive Obama ragdolls to arcade style fighting games with Obama and McCain as the two contestants (see above screenshot). Interestingly though, the projects also served as focal points for community discussions (through project comments) about the elections, acting as catalysts for community discourses on political topics. The Scratch forums (which is a separate part of the website) also saw a number of conversation threads about the election, where kids sought each others’ opinions about the candidates.

Connecting in a Time of Crisis

When a 9.0 scale earthquake off the coast of Japan devastated the country, the Scratch Online Community responded by sharing projects that expressed their support, from projects that expressed sadness and shock to projects that tried to spread optimism and hope. The above picture shows a gallery created by a Scratch member from Japan to collect related projects (as of today, there are over 100 projects). In addition to creating original projects in response to the earthquake, one member started a “remix chain”, asking her friends to remix her Scratch project to spread hope for the people of Japan. As her friends remixed her project, other members began to notice and remix as well. The figure below shows the resulting remix tree, with her project in the middle and the links point to other remixed projects. Soon her project reached became the top remixed project that week, sending her project to the Scratch homepage for the rest of the community to see. Overall, the project was remixed 87 times.

Engagement within the Scratch Online Community

Scratch members have also engaged and expressed their opinions regarding Scratch community policies. These suggestions and expressions have been in the form of project comments, forum posts and in some cases, emails to the Scratch team at MIT. There is also a separate website called Scratch Suggestions (http://suggest.scratch.mit.edu) where members of the community can post and vote on ideas and suggestions. Also, there has been at least one instance where dissatisfied members of the community have taken the Scratch website source code (available publicly under an Open Source license) and have tried to create a parallel community of their own.

Discourse & Debate on Community Policies – Sharing and Remixing

When members share projects on the Scratch website, projects are immediately shared under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en), meaning members are free to share and remix these projects. Anyone with a registered account can download the source project, which gives access to the Scratch code and all media assets such as images and sounds. Many members have found this a valuable feature to learn from others by looking at project code, exchange assets, and even engage in remixing activities such as chains and contests [2].

However, this policy of open sharing and remixing has also been controversial in the community, with members equating remixing to stealing. While the website supports automatic attribution when a project is remixed, studies suggest that this feature is not enough and that manual credit given by the remixer is more valued [1]. Members have started “petitions”, in forms of projects, forum threads, and comments, to change the remix policy. For example, the above image shows a suggestion posted by a member in the Suggestions space on the Scratch website, asking the Scratch team to allow project authors to decide the remixability of their own projects. Other members have also acted more aggressively against remixers, creating “vigilante groups” to identify and rally against “copiers”.

Despite such strong disapproval of policy, Scratch Team members continue to uphold remixing as a valuable practice in the Scratch community for members to learn and develop new ideas. The response from Scratch Team members have ranged from having conversations with members about the policy to banning members who verbally attack remixers through comments or projects.

Other Forms of Dissent

Community members have also expressed dissent against community policies designed by the Scratch Team through other mediums. In a series of a series of web-comics (hosted through an external service), dissenters ridicule various members of the Scratch community and the moderators. The image below shows one comic of a Scratch Team moderator calming down a crying community member.

We believe a subset of the webcomics creators (though there is no way to verify it) then went a step further to take the source code of the Scratch website and host their own instance — in some ways trying to create a “fork” of the community. The site, however, was short lived and all we have now is a series of screenshots of their home page. The image (with profanity blurred out) below shows a banner from their front page describing what members can do on the website.

Conclusion

These examples showcase just some of the expressions of civic engagement on the Scratch Online Community. The Scratch motto is “Imagine Program Share”. To support such a motto that calls on members to express themselves, the Scratch Team works to create an inclusive and welcoming environment. However, to maintain that environment, Scratch Team members must balance such open and diverse expression and creativity with community well-being. Our second research question explores how such expressions of civic engagement can affect the various actors in the community (members, moderators, parents/educators).

References

[1] Andrés Monroy-Hernández, Benjamin Mako Hill, Jazmin Gonzalez-Rivero, and danah boyd (2011) Computers can’t Give Credit: How Automatic Attribution Falls Short in an Online Remixing Community. In Proceedings of the 2011 annual conference on Human factors in computing systems. [2] Jeffrey V Nickerson, Andrés Monroy-Hernández (2011) Appropriation and Creativity: User-Initiated Contests in Scratch, 10. In Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.