I gave an Ignite talk today at the MIT-Knight Civic Media conference (#civicmedia). Wow, that went so fast! I didn’t quite share all I wanted, but if I could sit down with you over a cup of coffee, this is what I would have said. If I may be cheesy for a moment, these were really my most heartfelt points. So, my lucky ducks—read on for the full spiel!

I’m going to tell you about an exploration that really began with an interest in public space and a pet question of mine: Where does a postcard sit between a letter and an online petition?

I love the physicality of an artifact like the postcard. When we pick postcards, we do it on an aesthetic level that communicates something. And then there’s the intimacy of handwriting, even if what you write is just a blurb. Last night, someone described it as the tweet version of a letter.

So: I love neighborhoods. I used to organize block parties and I was on the working board for a neighborhood organization. What I’ve learned is that spaces are reactive. There is no such thing as a zero-sum space. Even private properties, like houses—or in our case, a neglected apartment complex—have an impact that spills over onto the sidewalks, into the street. So dormant spaces trap the vitality of areas that surround them.

This is Vail Court. It’s off of Central Square in Cambridge. The family that owns it lives in Washington state. In the last 15 years, it’s fallen into disrepair and has eventually been declared as structurally unsafe. Nobody lives there. Neighbors around the court complain about drug deals, drunkeness and fire alarms that go off randomly. Some of these neighbors don’t feel safe walking by at night.

I went out to talk to people about the property and to collect postcards that I mailed, two at a time, to the owners. This is just off the busiest street in Cambridge, so it gets good foot traffic but by locals. My goal was to talk to neighborhood residents and daily passersby.

Here is a picture of the space. See those brown squares? Some nearby residents graffiti-ed the graffiti—they bought brown spray paint to cover up the graffiti on the building walls.

This conversation has been swirling around in the community for decades. We created a way to get that to the decision makers. It’s not just enough, though, to send off a physical artifact. There needs to be documentation for the community. And so I put up postmarked.cc where the owners could even respond directly to the community.

There were a few groups involved: I talked with the Cambridge Community Development Department, which encouraged me to try it out, because multiple inputs pushing for one outcome can be more effective than one channeled input where you’re trying to curate an outcome. I worked with the YWCA to distribute postcards at their women’s shelter, just across the street. And neighborhood residents, who have been talking about this for years, were just happy to do something and recruit their neighbors. And I should say, they did this even though none of them believed the owners would respond.

On the site, you can see over 50 postcards right now. These responses were mostly supportive.

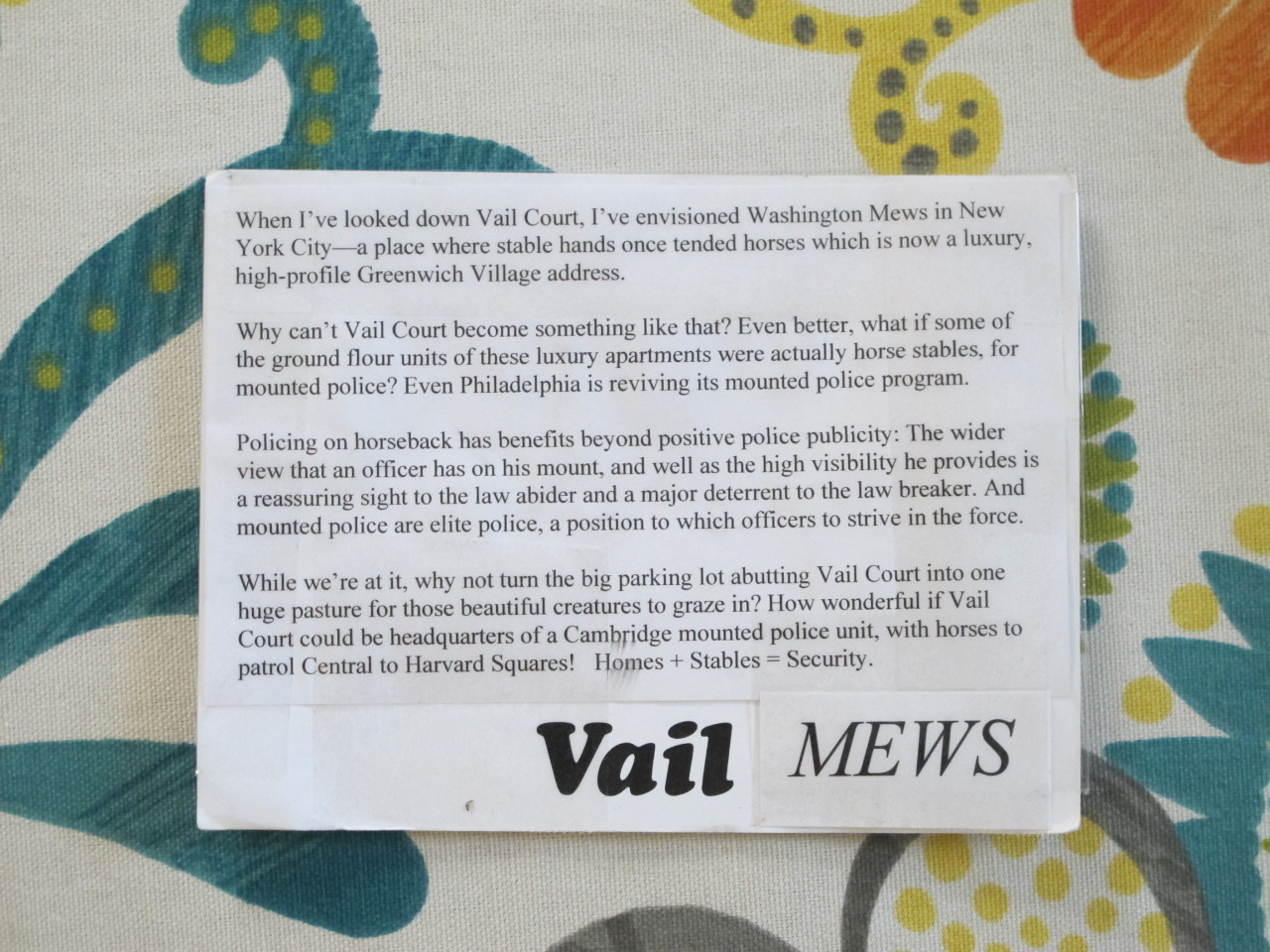

By far, this was my favorite postcard.

Now the question is why do this? On the next slide is a picture of Aiweiwei, who is a well-known artist from China. He was on his way to court to testify about the Sichuan earthquake, and how potential corruption led to shoddy school buildings in which hundreds of school children died. Before he could get there, the police cut him off and brutalized him. This is on video. He ended up at the hospital, and he would tweet a photo of his recovery everyday. Then he tried to file a complaint with the police again and again, also on video. In China, they know this will come to nothing. But it was important to make this disempowerment visible.

Then there’s PRISM. You’ve heard by now of the 34,000 investigation requests from the NSA, and the Fisa Court only denied 11 of them. Jonathan Corbett runs myNSArecords.com, where he files FOIA requests for people who want their digital records. He filed 500 FOIA requests around when we first heard about PRISM. He also helped these people file motions to quash. You’re instructed to mail this in, and as he was helping to fill out these forms, he found that there wasn’t even an address to send it. He had to call the courts, get the run-around, to learn where to send them. One of my reporter friends is fascinated by Corbett’s attempt, and he sums it up by saying, “it was never a court for you.”

Now! Corbett and his filers fully expect the motion to quash to be denied. And he points out that this would lead to more denials in one day than in the entire history of PRISM.

These two examples show us that assuming is not enough; sometimes you have to visualize disempowerment. If you know non-voters, they say that their vote doesn’t matter anyway. But it’s not just enough to assume powerlessness. Sometimes you have to show how disempowerment has been embedded into a system.

So other lessons. One of the most common questions I got was “Well shouldn’t we be going through the City of Cambridge?” People were waiting for permission to act, trusting that somebody official would set up the channel.

There’s a lot of resentment in this community that has been building up for years. But when it came down to writing, neighbors actually wrote really supportive invitations to change the space. Many calls were for affordable housing, gardens, an arcade, a farmers market, but most just expressed what it’s like to live by this space.

I was in Beijing this year, where I got to think about perceptions of public space. In the U.S., it’s really tied to physicality and separating commerce from space. When we spoke to Aiweiwei, who’s a prolific tweeter and obsessive documenter, he said the Internet is the public space; there are very few public spaces where people can gather in Beijing. Too many people, and the authorities get worried. So people reappropriate space. For example, IKEA is the place to go. You walk through their showcases, and people are napping on the beds. They’re not homeless, they just wanted to snooze. And IKEA’s cafe is actually the hottest seniors single scene in the area.

But what this means is that their “public spaces” are mediated by private enterprises. But the thing is, if that’s as good as it gets, fuck that it’s private and part ways with expectations, because it’s also a place to be together.

This is the third and final part in a series on a public art project to create a space for dialogue between a concerned community and the owners of a dilapidated Cambridge property.

- Part I: Postmarked: A public art approach to neighborhood civics.

- Part II: Postmarked: Negotiating [dis]empowerment in civic art