This week I am working on a model to map out civic actions in China. I borrowed models on social movements in the field of political science and added one dimension, the level of centralization of the media involved in the civic actions, to understand various types of civic actions in China. I do not intend to include all forms of participations but to provide an analytical method when categorizing them.

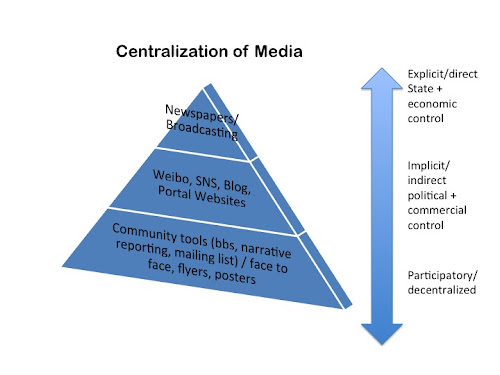

1. Hierarchy of Media

Newspapers/Broadcasting: State-owned national newspapers (People’s Daily), State-owned TV (CCTV), provincial party owned newspapers/TV, Southern Newspapers (South Weekend Newspaper, which is ideologically liberal in contrast with pro-party media).

Weibo,SNS, Portal Websites,Blogs: Sina Weibo, RenRen SNS, Kaixin SNS, Sina News, Sohu News, Netease News, Sina Blogging, Sohu Blogging. They are owned by large private corporations such as Sina and Sohu which adopts sensitive words filtering. It is a compromise between the urge of the development of information technology sector and traditionally rigorous censorship. On theone hand, the commercial interests drive the growth of micro-blogging, social networking, and blogging services provided by these companies, which boost the general economy. One the other hand, in comparison with various competing small companies (eg. the shutdown of Fanfou), the contents from the centralized service providers are easier to control by the state, specifically, the Party Ministry of Propaganda, Press and Publication Administration, Radio Film Television Administration.

Can your voices be heard from Weibo(it fails to address daily issues)?:–commercial interest comes first;elites domination;retweeting ( less original contents);topic disappears quickly;

The other category is described as community tools in this chart. It addresses common concern regarding both geographically aggregated communities and dispersedmembers but with shared aspects of identity with communities. Traditional communication forms such as face to face communication, flyers, and posters can still effectively generate information flow between these actors. At the same time, community members using emailing lists, local BBS, online forums and texting through mobile phones form the online networks that enable discussions on issues ofcommon concern, and have the potentiality to generate collective actions.

2. Civic Actions in China

Figure 2 Dimensions of Civic Actions in China

In the above table, I do not intend to exhaust all types of civic actions in China (more comprehensive categories of political participation can be found in Shi’s work, and Yang also demonstrated many forms of activism), but rather I would like to list some dimensions that are useful to describe the differences of these types. The indicators, to what extend the actions are organized, how institutionalized the actions are, and how strong the advocacy of the actions are, are traditionally used in political science theories when categorizing varied social movements (Dingxin Zhao, 2005). The numbers in this table ranging from 1 to 5 are only meaningful in ordinal scale, not in interval and ratio scales (numbers can only be compared within columns, but no plus or minus within numbers in a same column). In the column of centralization of media used in actions, routine politics such as voting and party meetings, can only attract attention from local newspapers, and if it is voting for district congress representative among college students, university newspapers might cover the story, while national newspapers will neglect these political actions. Routine politics are highly institutionalized in Chinese political system in contrast with radical social movements that happen spontaneously, which explains the numbers 5 and 1 in the two categories. The ability of generating discourse is another factor that defines the types of civic actions, the economic reform led by Central Communist Party, for example, the entry to WTO, comes with a discourse of neoliberal economy generated through wide coverage from national media, while in contrast, daily practices of online activism are hard to find voices in a larger scale. The last indicator, the class reflects the social reality of current China that the social inequity and stratification has impacted almost all aspects of people’s life. Regarding civic actions, the class classification is still significant as those participating in pro-democratic activism are more likely to be elites. I have to admit here that most of the conclusions come from my subjective observations, and I hope in the future or in my master thesis I might adopt cases studies, and survey reports to support my speculations.

It is also worth noting that the actions are not in their static forms, but rather they changes with time. Routine politics used to barely receive attention from individuals or the coverage from local newspapers is not of ordinary people’s concern in the early 1990s, and in 1998 since the election law that permits direct election at lowest administrative level was passed by the national congress, some routine politics such as voting for local villages have captured the public’s attention. In the past decade the fact that more independent candidates have stood out also changes the voting behaviors. A recent news (need to confirm) from Tianya BBS saying college students from Fudan University filled out names of movie actors or left blank on the vote paper. In short, the types summarized in the tables are not comprehensive and in reality there are far more nuances than researchers can imagine. If we examine the civic actions diachronically even more complexities will bring about into our scope.