One reason I make things on the Internet is a strong belief in the original powerful idea behind the web itself: that links can radically transform the way we tell stories and experience the world. Today, I saw an amazing example of this, via Sarah Espiner, my former colleague at the Ministry of Stories.

“Imagine what it would be like if you weren’t able to make your own decisions.” That’s the tagline of Give Girls Power, a beautiful choose-your-own-adventure web advocacy campaign by the UK wing of Save the Children (update: the design was done by HomeMade). They hope a public petition will convince the UK Government to expand its existing foreign aid funding for contraceptives and family planning. Give Girls Power brilliantly illustrates a core insight about second person storytelling which has obsessed me for nearly a decade: some of the most powerful interactive stories involve denying readers agency.

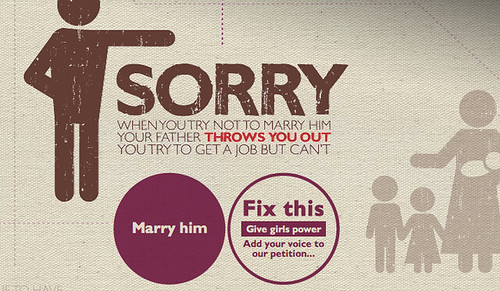

In Give Girls Power, disempowerment is a call to action. The story is an infographic prezi-style choose-your-own adventure about marriage and childbirth for women with limited choice, family planning, or access to contraceptives. The story puts readers in the place of a girl who is being pressured into an early marriage and potentially deadly reproductive practices. Readers are repeatedly given a situation with two choices. For example, you’re 16 and you want to be a nurse. Your parents want you to marry an older man and start having children. Do you marry him or not?

Many women can’t make such a unilateral decision. If you say no, you haven’t gained independence; you’re just expected to marry someone else. Eventually, your desire for personal agency reaches a genuine impasse. It’s at this moment that Give Girls Power is brilliantly clever. The girl in the story might be stuck, but you the reader aren’t. A “Fix This” button sends you to a campaign page directly related to the issue that disempowered your character.

This makes a great story and a brilliant campaign. I could geek out over this for dozens of pages, but here’s a summary:

- Some of the most powerful literary works of interactive storytelling invite us to make moral choices for a character as if they are our own

- Second person choices like this very likely tap into fundamental parts of the human mind which we use to understand the world through imagination from a very early age

- Fruitless reader choices work particularly well at leading readers to explore social issues of disempowerment, in a Kafka-esque manner

- Our instinctive responses to these choices appear to go deeper than our stated religion or politics (pdf)

- Choices in the story are basically survey answers. By customising their call to action for different moral paths, Save The Children is theoretically able to tailor their campaign to people with different empathetic tendencies. Action 1 tells the story of an older married woman. Action 2 highlights a 17 year old unmarried mother.

Choose-your-own-adventure storytelling offers campaigns a fantastic ability to reach very different audiences with tailored calls to action. Compared to advertising-driven approaches, the story is elegant and transparent. It’s also possible that Save the Children could save data about your choices so they can tailor later emails to your interests and values.

This kind of storytelling can and should be more widespread than just advocacy campaigns. Interactive stories like this are the Socratic method of empathy. They offer a bridge across the limitations of our values and felt experience. When the ignorant skeptic in us asks, “why doesn’t she just say no,” the story can respond by narrating likely consequences.

Interactive storytelling (onscreen and onstage) has been used elsewhere in this way to expose gender inequalities. Before I write further, I need to acknowledge people who have been doing amazing creative work in this area for years.

Galatea, by Emily Short, explores the ways we objectify women; its main character is literally an object. Emily’s story, which draws from the Greek myth of Pygmalion, places Galatea in a museum long after Pygmalion’s death. The reader is a visitor to the museum and may observe, address, and touch the statue. In Short’s story, Galatea speaks back. Emily, who is one of the most insightful writers and thinkers on interactive fiction, keeps an awesome blog and frequently writes excellent videogame reviews across several publications.

FailBetter Games is one of the smartest companies in storytelling right now. Their mission is “to build strong worlds with real choices.” Through years of iterations on the game Echo Bazaar (2009), they have become incredibly good at designing engaging choices for readers: nail-biting decisions you don’t want to make, temptations to flirt disaster, and subtle dilemmas between desire and tragedy. Their most famous choice could easily be a moment in Give Girls Power. You the reader have been hired by the Comtessa’s father to find his missing daughter. You discover her genuine love for a social outcast, an affair which puts her at a deadly health risk. There is no moral high ground for your next choice (read more in a brilliant post on this by Yasmeen Kahn). Failbetter is now focusing on Storynexus, a platform for storygames (sign up for the beta here).

In Fate (2007) by philosophy professor Victor Gijsbers, the player takes the role of a pregnant queen who tries to protect her future son. She expects this son to be murdered by a ruler who will be threatened by the presence of a new heir. As a female character, the player of Fate is constrained by the limited agency possessed even by a queen.

Against All Odds (2005) is probably the most iconic example of disempowerment-based civic storytelling. Published by the UNHCR and translated into 11 languages, this informative and challenging Flash game invites players to “experience what it is like to be a refugee.”

The cleverest of these stories learn about their reader and tailor content to readers’ interests and values. Preloaded‘s game The End asks players questions about their views of death as part of the game’s narrative. The sum of those choices is mirrored back to players on a map of philosophies and religions. The game suggests further resources for readers to deepen their knowledge as well as braoden their awareness of other people’s views. I want to see more of these.

While I like Give Girls Power very much, I think we can also do much, much better. Firstly, the infographic style is wonderful and flashy, but it depersonalises the issue it tries to explain. While I love the idea of infographic stories, I’m deeply concerned that the infographic style leads us to think of each other as abstract rhetorical models rather than real people. It’s to the credit of Save the Children that their call-to-action pages offer quotations and stories from actual people.

Give Girls Power doesn’t teach us as much as it could. Their generic girl-within-patriarchy narrative has no detail, no colour, no life– just thorny social dilemmas. That makes sense for an advocacy campaign. What might the story look like if it were a work of journalism or documentary? In addition to including reported detail, the story might also invite readers to choose someone like them, offering a personal connection beyond big fonts and silhouettes.

Some of the most valuable designs point in a direction and inspire people to take an idea further. Give Girls Power is one of them. I would especially love to see journalism and documentary projects which draw inspiration from this campaign: inviting empathy through choice, illustrating disempowerment through frustrated choice, and tailoring the story to the choices of the reader.