Sina Weibo is one of the major micro-blogging services in China. According to a recent news report, Weibo has over 300 million users, and 100 million posts are generated everyday. In contrast with its counterpart in the West, a large number of studies on Twitter has been done, but the number of studies on Weibo is rather limited. Some researchers are constrained in studying Weibo because of language issues. For those who are sufficient in Chinese language, the research that has been done is mostly qualitative case studies. Thus, the question posed here is how to conduct large scale quantitative analysis of Chinese Weibo?

In comparison with qualitative case studies, large scale quantitative analysis on Chinese Weibo are limited because of the restrictions of Sina API to retrieve the data.The article on Chinese censorship by Bamman and others used the public timeline to retrieve the stream of Weibo posts. According to the Sina public timeline document, it returns the most recent 20 public posts. However, for researchers, it is still unknown if this 20 posts are representative to the larger Weibo posts set. Another approach is to fetch posts through users’ ID. WeiboScope, a project at Hong Kong University, has archives of posts from over 300 thousands users who have at least 1000 followers. During their presentation at the 10th Chinese Internet Research Conference, they showed their approach to the issue of censorship: they retrieve these users’ statuses every day, and compare to their archive to determine which posts are deleted. Another tool to retrieve Weibo data I tried is DiscoverText, in which users can set up their words to search, and searching time intervals, and the tool will return posts containing the words. Using both tools, I did a search of posts containing the word “Wukan (乌坎)” sent from March 23 to March 27. WeiboScope returned me around 200 items while DiscoverText fetched around 1000 items. I am not quite sure about the reasons for the distinctive results, but my guess is that one only looks at popular users’ posts while the other fetches from the general public timeline.

Despite these restrictions, I still think the chances of conducting large scale quantitative research on Chinese Weibo lie in the refinement of the research questions. The limited sample set can still be representative to the limited scope of the questions. Specifically, instead of asking about the frequencies of certain key words appearing on all the Weibo posts, researchers can shift their perspective to a limited scope that only focuses on an interesting group. For example, Weibo provides lists of users in different occupations, and if the research questions only relate to posts produced by a certain type of users, such as journalists, researchers can directly make use of the list.

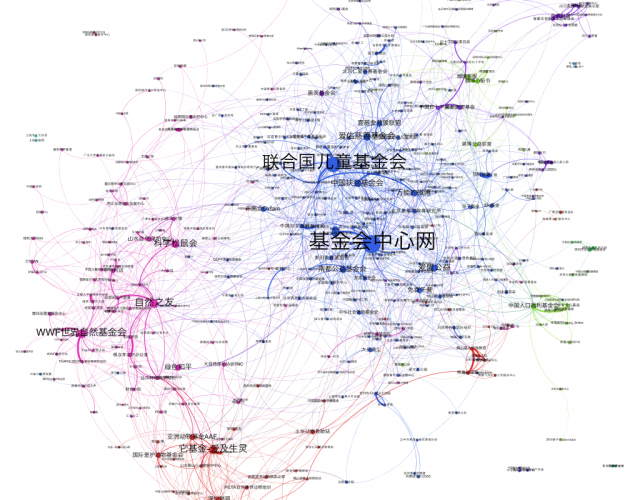

Following this idea, Wei Wei and I have been working on a project mapping out the NGO networks on Weibo. The figure above shows who mentions whom among NGOs on Weibo. The node size is the in-degree centrality and the colors show different communities. The NGOs are largely clustered by their working domains such as saving animals and evironment protection. Large NGOs, for example, WWF, UNICEF and China Foundation Center are frequently mentioned by other NGOs on Weibo. We are still in the process of collecting data and especially welcome any suggestions on data scraping on Weibo and network analysis methods. The broader topic of NGO networks we are interested in is how the social media empowers grassroots NGOs. Resources for media coverage from mainstream media on grassroots NGOs are limited because they cannot compete with government affiliated NGOs for media attention, so we contend their integrated use of social media may amplify their voices and construct a network that challenges the offline hierarchical positions. Although the figure above shows large international organizations occupy key positions in the network, we might also look into dynamic data to see the change of the structures instead of this static picture.