What would we learn by comparing the texts and teachings of an entire religion across culture and language?

A few weeks ago, I posed the idea of global prayer metrics. I compared the function of prayer notices to journalism and reflected on the theology of quantifying prayer. Today’s post is a thought experiment and dataviz on measuring religious activity across cultures.

During a brainstorm with Andy Moore and James Doc at the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students a few months ago, we imagined an online artifact that would collect information about Christians’ religious experiences across culture and language. We could post an online, multilingual edition of the Bible and invite people to annotate it with interpretations and experiences. Would those interpretations converge, or would we see significant differences across different sects and geographies of Christianity? At the moment, Westerners have the loudest voices; could we channel insights from this dataset to cultivate a better appreciation of each others’ values?

After our chat, I realized that existing sermon datasets can be combined into a comparative dataset of religious focus. Churches with websites often publish their Sunday sermons online, often with links to audio recordings. Both my church in the UK and my new church in Boston have online interfaces for filtering and selecting those recordings based on scripture text. To develop a comparative sermon map, it wouldn’t even be necessary to track down every church website. Sermon podcast aggregator SermonAudio hosts and archives over half a million sermons by textual reference, date, speaker, and location (although that’s still only a small sample of American churches).

What They Preach

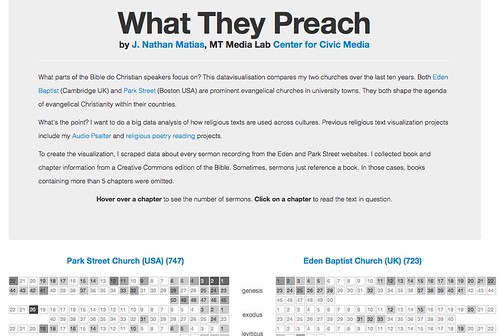

I’m stuck inside this Sunday with a cold, so I decided to build a heatmap which compares my UK church with my new American one. Using datasets from the last ten years of sermons at each church, I created a visualisation of what parts of the Bible my churches’ sermons focus on (Click to view “What They Preach”). Here’s what I found:

It’s a well known fact within Christianity that you can’t learn the Bible by going to church on Sunday. It’s just too big for twice-a-week, hour-long lectures. Regular personal and group study are absolutely essential for anyone who’s trying to maintain an active, enquiring faith. Nevertheless, the overall pattern at these churches does include a mix of life advice and major doctrines. I admit that the prevalence of Galatians over Romans is surprising. A great deal of basic Christian theology comes from Romans, but it’s passed over in favour of St Paul’s other writings.

The most popular passages are different across churches. Park Street loves the beautiful Psalm 19, which has received 10 sermons. The Ten Commandments receive 10 Park Street sermons but not a single dedicated sermon at Eden (though I have heard them frequently referenced). Park Street has covered Jesus’s “Sermon on the Mount” 13 times, to Eden’s 3. St Paul’s beautiful encouragement to practical love within churches was the subject of 17 Eden sermons but only 2 of Park Street’s. Likewise, the epic narrative history of the idea of faith in Hebrews 11 received 9 Eden sermons and only one at Park Street.

Overall, Eden’s sermons appear to feature a greater diversity, while Park Street tends to focus repeatedly on a core set of topics and texts. As someone who is part of both communities, this makes sense to me. While Park Street throws itself into serving Boston’s high-turnover populations, Eden focuses on connecting the region’s students into a community of faith with a longer trajectory.

It’s also possible that the data shows a more embattled American church. Numerous sermons on the book of Genesis at Park Street participate in the current creationism debates in the United States. Park Street has also dedicated substantial time to the book of Daniel. American Christians in universities often compare themselves to Daniel, imagining themselves as covert believers within enemy institutions.

Sermons at both churches prefer theology to stories. Two years ago, my friend Dirk Jonkind gave a brilliant talk on the importance of stories in Christianity. Comparing intellectual and relational knowledge, he urged us to go beyond opinion and rules to explore God’s character through the Bible’s narratives (mp3). This heatmap has convinced me to focus more of my personal reading on narrative texts.

Today’s experiment has convinved me that we can learn a great deal from comparing the aggregate focus of churches around the world. Do you know of a good dataset or have another idea for the data analysis of religion? Email me or add a comment below.