In an age of smartphone cameras and ubiquitous surveillance, what place is there for artists in politics? What does journalistic, political art look like?

This summer, I’ve been exploring the role of comics in nonfiction, blogging about Nick Sousanis’s academic comics and interviewing Brooke Gladstone and Josh Neufeld with The Atlantic. I was excited to hear Molly Crabapple at the Berkman Center today.

Molly Crabapple is an artist and writer living in New York. She recently reported and sketched the Chelsea Manning trial. Her gorgeous, compelling 2013 show, Shell Game, earned her the title Occupy’s Greatest Artist in a Rolling Stone review. More recently, she has been making art about Guantanamo Bay.

Molly starts out by telling us about the only two people who got angry when she drew their pictures. The first was a religious fundamentalist in Fez’s old city in Morocco. She went there at the age of 18, hoping to develop as a journalist artist. Frustrated by the tourists and wanting to show that she wasn’t like them, she sat on the street and drew. Molly made a lot of friends, except for one man that tore her sketchbook out of her hands and threw it away. When you draw, Molly tells us, you’re committing a subversive act; you’re interpreting a context.

The second person who didn’t like her painting was a New York police officer who she drew in a New York court. “You are looking at me,” the officer said. “Anyone who looks at me is asking for trouble.” The defendants broke out in laughter.

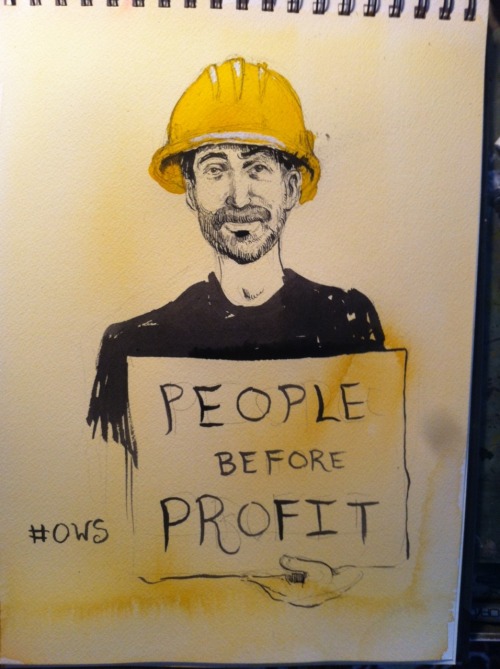

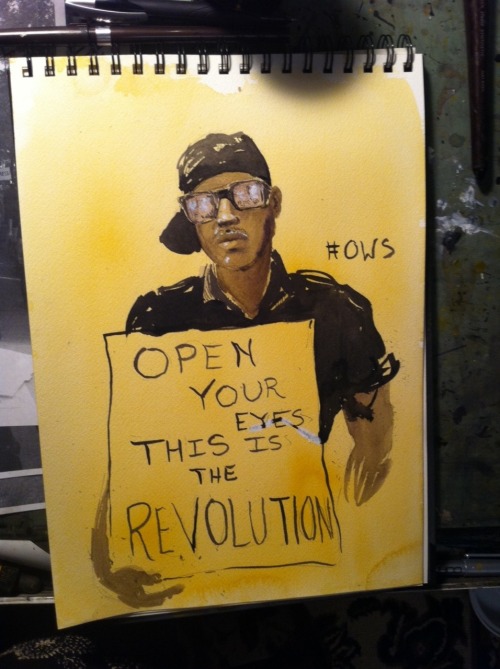

I’m an artist, Molly says. I smear pigment onto giant pieces of wood until I think it looks cool. I also do illustrated journalism, using my sketchpad like a camera. Molly shows us pictures she drew from Zucotti park in Occupy. The news narratives said that occupy protesters were dirty and grubby; Molly’s art presented the reality.

I used to be obsessed with photographers, says Molly. But before cameras, every image was drawn by artists. Whenever there was anything that needed reproduction, artists would draw it. Molly shows us a plate from Goya’s Disasters Of War. Unlike photography, Molly says, paintings can editorialise. During the Paris commune, Daniel Vierge drew the women of the commune. Next, she shows us Otto Dix‘s Skin Graft, an example of his anti-war illustrations of veterans.

Molly shares her enthusiasm for Ott’s other work, including this stunning painting of dancer Anita Berber.

Truth, Drawing, and Photography

We tend to assume that photography is true. Goya’s painting of rebels being executing by Napoleon’s soldiers was imagined. Photography on the other hand, can show us things that actually happened.

In our time, every single thing that can be photographed is being captured. Everyone has camera phones and everyone is also being surveilled. Where does that leave art now?

The outstretched camera phone is one of two global symbols of rebellion, Molly tells us. The other is the Guy Fawkes mask. The cameraphone is accountability for people in protests. The network appropriates these images (Osman Orsal’s image of the “woman in the red dress” during Occupy Gezi), sharing and remixing them. Officer Pike (pepper Spray Cop) would have been anonymous under other circumstances. The Internet made him a Meme.

Cameras make government accountable, but citizens also live under constant surveillance. The line between citizen media and government media is merging. As we view things with our phones, that data is also being shared with governments, she tells us.

We’re trusting photos less and less. Earlier this year, John Kerry used a photo by Marco di Laruo to justify the military intervention in Syria, but it was actually from Iraq. Syrian rebels have published photos of them holding toy guns. Even when photographs have documented something conclusively, consequences aren’t guaranteed. The officer who killed Oscar Grant wasn’t charged with murder.

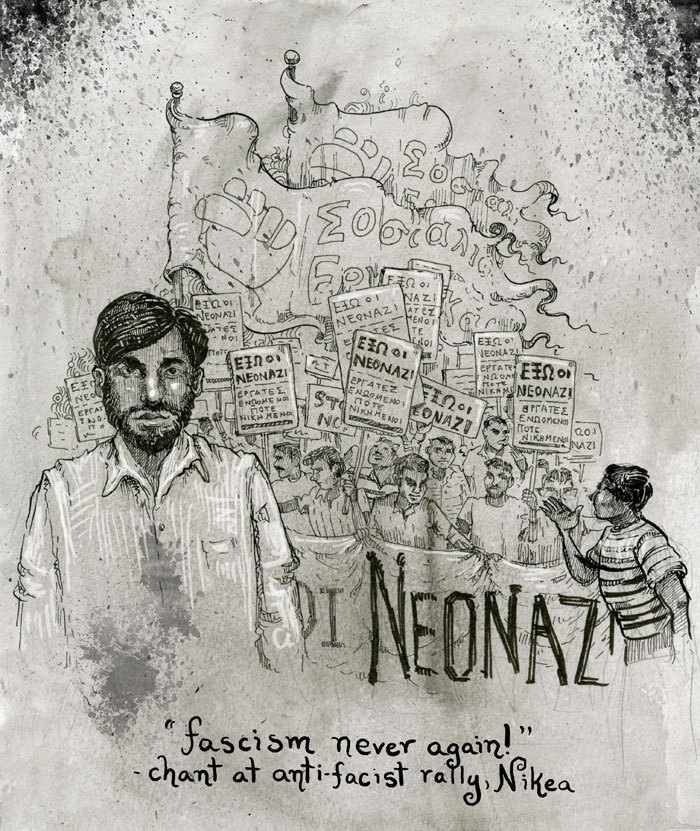

Why draw in the age of photography? Molly has cultivated a journalistic vision of drawing current events in physical protests and online. For Discordia, her book on Greek protests with Laurie Penny, she combined material from original photographs and images online into drawings that represented what had happened.

For Shell Game, Molly tried to create surreal, decadent, allegorical art, votives and altarpieces to the global protests of 2011. To create them, she interviewed people from Occupy, Anonymous, Nawaat to make sure that the pieces were accurate and representative.

There are some places where cameras can’t go. Crabapple recently spent two weeks in Guantanamo in two trips, trying to draw the island. What she settled on was the censorship. In one image, she draws an officer as he demonstrates force feeding. Similarly, when she drew prisoners through bulletproof glass and one way mirrors, she wasn’t allowed to draw prisoners’ faces. She also drew the “cultural sensitivity officer” at Guantanamo. Journalists were also banned from drawing camp layout. She wasn’t able to draw more than two buildings, locations of cameras, and locations of doors. The censorship at Guantanamo is so complete that they give you a powerpoint showing you the only three angles that you’re able to photograph. Many of these things could only be presented with drawings.

There are other reasons while people might not want to be drawn. Sometimes, activists don’t feel comfortable having their identity reviewed. In Greece, the police wouldn’t allow you to draw them and it was probably dangerous to look at them closely. In some places, there are no cameras. When Crabapple was arrested during Occupy Wall Street, she was put in jail. She scratched drawings into the styrofoam cup they gave her and reproduced it from memory.

Artists can take memories and make them real again. Molly shows us a panel from Joe Sacco’s drawings of Palestinians being interrogated. Cameras can be confiscated, Internet can be cut off, but people will continue to draw. She shows us some of David Choe’s drawings from solitary confinement using soy sauce and his own urine.

The act of drawing also sets people apart as more than just the subjects of bureaucratic processes. Molly shows us a drawing she made of Hisham Sliti, based on a photo taken by the Red Cross.

Large collections of citizen photos expose us to the chaos of multiplicity; we also need artists to extract the singular, who can go where cameras cannot, who can distill the essential. Picasso’s Guernica doesn’t show what a body looks like after a carpet bombing, but they do show us the horror of war. Images get under the skin of power and they get to the edges of our heart.

Questions

Matthew Battles asks about rights management and protest images. Crabapple tells us the story of her Occupy vampire squid, which was quickly turned into T-shirts. Madonna tweeted her Free Pussy Riot image, and before long, the press was reporting it as Madonna’s creation. The Network Eats All, she says, talking about the tattoos and all the young people who are imitating her style.

How do you fact check art, an attendee asks. When Crabapple does writing, her work is fact checked like any journalist. It’s harder for her art because photographs are often not allowed. When you draw something, or even when you take a photo, there is always an editorial slant.

Who’s your audience, someone asks. “I want to make political art for people who don’t ordinarily think that politics is for them.” Political art often draws from 1920s graphics design, and while those images are compelling, many people ignore it because they assume it’s not for them.

I asked Molly about Susan Sontag’s critiques about the role of photography to foster peace. Sometimes, they can unintentially do the opposite. Molly responds that images can sometimes desensitize people to violence. Drawing our attention to Otto Dix’s drawings, she shares a hope that drawings can still shock people and get past their defenses.