Panelists: R. Stevens (Diesel Sweeties), Sam Brown (Explodingdog)

Growing from the backwaters of nerdy scribblers uploading their doings onto the web, webcomics have grown into vast, mighty engines of culture online in the past decade plus. Whether it’s the firm geekery of xkcd or the more obscure dabblings of Achewood – webcomics have, more often than not, come to be the shared cultural anchor-points in the broader internet.

This panel brings together Rich Stevens and Sam Brown, who have been deep at the dark, beating heart of webcomics-land from the very beginning for a casual Q&A about the big picture of where things have been, where things are, and where they’re going.

“Thank god for the Internet. Don’t ever go to old media when you can make it big on the Internet,” says webcomic artist Rich Stevens to the audience. This panel is in a smaller auditorium than the first few talks, nestled in a side hallway off MIT’s Infinite Corridor. The audience, however, is filled with loyal fans, some of which appear to be artists aspiring to create webcomics of their own.

“This is just going to be a casual Q&A session,” says Rich. The creator of Diesel Sweeties has published webcomics for over a decade. Sitting next to him is fellow webcomic veteran Sam Brown of explodingdog, who has decorated the blackboard with cartoons. The audience wastes no time breaking out into questions. One fan brings up gamer webcomic Penny Arcade. “It’s gotten so big that it has its own expo, while other comics fail. What’s the difference between success and failure when it comes to webcomics?”

“As you heard in the keynote, when people try to force a meme for commercial gain, it seems to fail.” The same thing holds true for webcomics, says Rich. He points to Jeph Jacques’ Questionable Content as an example of a webcomic that grew organically, having originally been based around small community forums.

Similarly, the two panelists also had humble beginnings—both went to art school, with Sam studying fine art and Rich in the design stream. However, they have very different approaches to their webcomics. Sam works on his comics sporadically. “I don’t update regularly. I’ll take months off and work on a different project, but I always like coming back to it, because I always get new ideas.”

Rich, on the other hand, adheres to a strict schedule. He explains, “It just became a thing, updating at midnight. I can’t not do it. That’s all there is to it, you have to make yourself ill.” For him, the daily comic acts as a sort of a journal, whereas Sam’s less regularly updated comic is more like a gallery when he looks back on his work.

Another audience member asks about fan appropriation of comics. “For memes such as Nyan Cat, the internet has its clutch of ownership upon it. But what about your comics? How comfortable are you with other people using your characters and creations?” The two respond positively to fan engagement. Sam responds, “That’s what’s so exciting about the Internet. You just send it out and it goes a million different places and you don’t know what’ll happen to it.”

Rich is similarly open to this kind of fan engagement. He says he’s fine with people remixing his characters and content, as long as they don’t simply copy his comics and claim it as their own. For commercial adaptations, on the other hand, he is more skeptical. Asked whether he’d prefer a million dollar Hollywood adaptation or a fan adaptation of his comic, he jokes, “I’d take the million dollars, and then do everything to sabotage the adaptation so that it failed. Then I’d go back to doing what the fans want.”

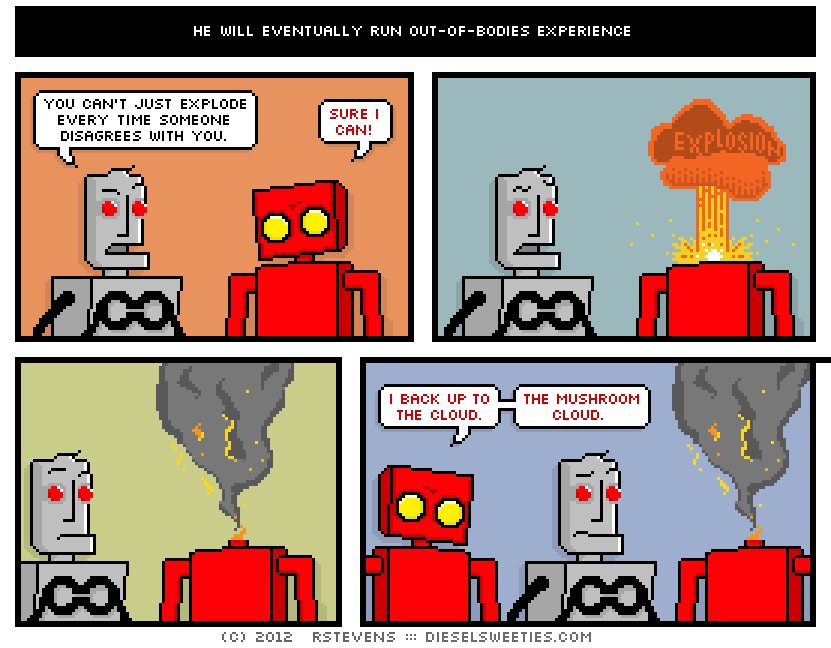

The discussion then progressed to the topic of art styles. Rich originally modeled his characters on the old-school Mac user/usergroup icons, and his unique style grew from there. “I could have never done this level of complexity if I hadn’t practiced for five years,” he explains.

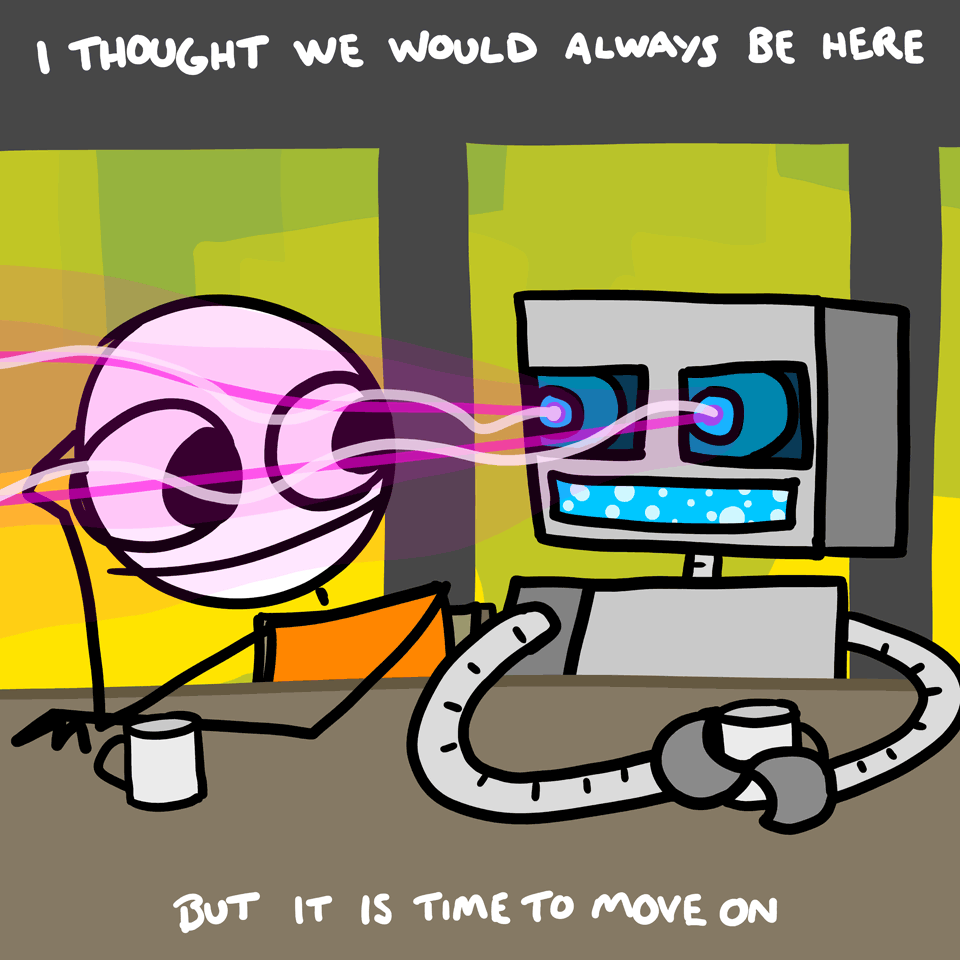

Both Diesel Sweeties and Explodingdog have been going on since 2000. Sam’s irregular schedule has actually enhanced the longevity of his webcomic. “I don’t update much at all, so I don’t see myself burning out. Whenever I do it, I enjoy it.”

Rich is just as committed to continue producing content. “I’m going to do it until I can’t stand it at all anymore. Then I’ll spend the rest of my life selling iPhone chargers on Kickstarter.” This is not foreign territory to Rich, who has produced a DRM-free collection of his strips, fully funded on Kickstarter.

Despite optimism for the future of webcomics, Rich expresses nostalgia for the earlier days of the Web. “Don’t take this the wrong way, Internet.” He says that it used to be more “tethered” and thus the types of online communities back then—such as message boards—were more intimate and more likely “to do neat stuff.” Rich recalls the early years of his career, when he would promote his content by submitting links to nerd link-sharing website Slashdot, the namesake of the Slashdot effect. “The Internet was so much smaller then. A single good link could make all the difference. Now it’s become so fractured. Things just churn up, and you can’t control it.”

Still, neither Sam nor Rich seem to worry too much about marketing their comics. They agree that the best approach was to simply produce good content and let it spread via word of mouth. There have been a couple of exceptions to this, such as Rich getting Diesel Sweeties t-shirts into CBS’s Big Bang Theory. “I’m a big fan of watching for opportunities to send the right person something,” he explains.

Letting their webcomics spread organically was a good decision, as the audience has changed a lot over time. Starting out, Internet usage was tied to physical location and they could actually observe how their comics spread in a very localized, natural way. This is no longer the case, as Rich is quick to point out. “Now they’re all grown up and just read everything on their iPad. Everything’s flattened out.”

Letting their webcomics spread organically was a good decision, as the audience has changed a lot over time. Starting out, Internet usage was tied to physical location and they could actually observe how their comics spread in a very localized, natural way. This is no longer the case, as Rich is quick to point out. “Now they’re all grown up and just read everything on their iPad. Everything’s flattened out.”

But webcomic audiences have also changed for the better thanks to this untethering of the Internet. Sam explains that, while webcomics started out as “the typical nerdy guy type of thing”, it’s so diverse today, drawing in significant female readership. Rich compared this phenomenon to Japanese manga: “Everybody reads it, but nobody knows each other. So there’s no stigma.”

Catering to these broad audiences can be difficult, of course. Asked whether they’ve ever contemplated writing longer serial stories, both Sam and Rich admit it’s too difficult. Rich envisions Diesel Sweeties as being “Peanuts with sex.” He considers himself a bad planner. “It’s one of those things that doesn’t come naturally. We wish we could.” Sam further explains, “We have to really commit to doing it. It’s really hard to do something that’s too long.”

After a few more back-and-forth questions from the fans, the discussion eventually leads to the topic of ebooks, and how that industry has affected webcomics. Rich, having himself produced an iPad edition of his collected comics, is positive about the medium. “Apple has trained us to spend small amounts of money,” he says. As an example, Rich points to Bill Amend’s FoxTrot, which makes more money via these small collections on the iTunes store in a month than it does by traditional sales in a year. “He’s making them available—easily, and people are responding positively to that.”

The Q&A session continues, and at one point Sam reveals that, while he’s not bothered by it, he doesn’t think that the webcomic label is necessarily accurate. “I don’t consider myself a comic. I’m just friends with cartoons,” he explains. “The word comic insinuates that they must be something funny. I don’t think about how to be funny.” Rich sympathizes with this sentiment, and cites how comic books are sometimes referred to as funny books. “And then nobody takes it seriously.” Sam says that there are also narrative drawbacks to the “comic” label. He adds, “I also feel like you get more out of humor when you’re not expecting it.”

Take for example the Red Robot character in explodingdog—Sam created the character back in 2000, and since then it’s become a sort of in-joke webcomic artists. The Red Robot has appeared in hundreds of other webcomics, including Diesel Sweeties. Rich elaborates, “I just ripped off Sam, and I’m lucky he’s a nice guy.”

The discussion eventually ends up on the topic of how Sam and Rich initially made the leap into making webcomics. Sam recalls how he got laid off, like many others during the dot-com bust. He took it as an opportunity to make a life change. Rich, on the other hand, had voluntarily quit his job, having saved up for six months. He told his dad, “If it doesn’t work out by next year, I’ll get another job.” Both artists have been producing webcomics ever since.

Despite his success, Rich says his family members don’t “get” what he does. His “non-internet” relatives think that he sells t-shirts. Still, he continues to find opportunities to connect with them; he tells us about how he gave his mathematician uncle—who knew nothing about his webcomic—a Diesel Sweeties t-shirt featuring the value of pi rendered in the image of a Pac-Man cherry (“cherry pi”). His uncle loved it. Rich explains, “You find what they understand, and then you give it to them.”