What is social change? In simplest terms, in signals an alteration to some pre-existing social order, not necessarily for a progressive cause. Last week, the students of Introduction to Civic Media were instructed to break into groups and develop their own model that would outline some theory of social change. This exercise was largely informed by our assigned readings that covered ideas of political economy and marxist interpretations of media industries. In short, our readings underscored how media systems serve a central role in maintaining the status quo in societies.

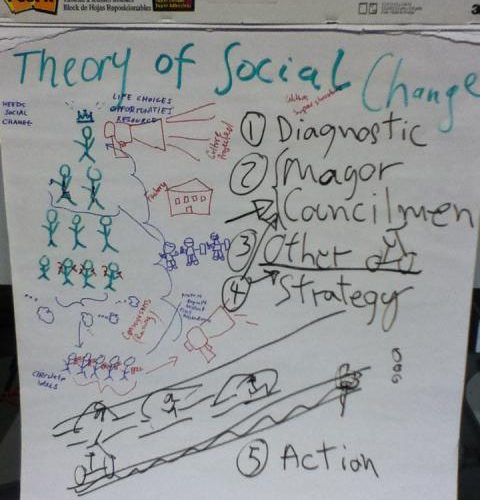

If overwhelming power rests in the hands of small groups, then how can social change take place? In groups of 3-4 people, the students of our course were able to develop models for understanding how social change takes place, especially considering the role of media. In my own group, our theory of social change had two basic models: a formal and informal path towards social change.

Our formal path towards social change was represented by a bicycle path, where individuals are cycling along trying to carry out their lives as smoothly and without interruption as they can. The catalyst towards social change comes when one of these cyclists notices many factors that are interrupting the smoothness of the trek, which in turns leads to meditation and the development of consciousness around the obstacles faced. Feeling the need to sidetrack due to protruding obstacles, such as uneven paved roads that can represent the inability to access childcare, the cyclist veers of the path and initiates the formal process of contacting local government officials and petitioning for the bicycle path to be fixed. This model is formal because it uses pre-existing institutions and structures to generate change from within the confines of that system. In the real world, this may entail setting up meetings with local officials, submitting paperwork, proposing policy or legal initiatives, etc. We were unable to develop the role of media into the formal model of social change due to time.

The other part of our model consisted of an informal approach to social change. This model assumes that the formal bicycle path has already been attempted and failed, perhaps due to bureaucratic red-tape or because those seeking social change are disenfranchised from the formal process altogether. We were also able to identify several key structures and elements that are central to understanding social change, social as hierarchies, distribution of power, and relationships. To demonstrate the distribution of power, we developed a multi-tiered pyramid that represented how power is concentrated into the hands of few at the top, while there is strength in numbers at the bottom. We added small details to give each level some character, such as a crown on the individual at the top (elites), suits and ties in the higher levels (bureaucrats and managers), and hammer and sickles in the hands of working people at the bottom. Near the top of the pyramid also lies the power to determine opportunities, resources, and life choices for large segments of society. To the right of the pyramid, we included a giant megaphone which can be easily used by those with power and influence to disseminate their ideas and culture. Our diagram would have not been complete without including a factory and riot police, with are all behind a fence that signal that they are privately owned.

How is social change generated within this informal model? Similar to the bicyclist model, we believe that social change truly begins with the awareness of problems in society. This awareness was represented by “thought bubbles” that emerged from the working class, which in turn generated consciousness of issues. This consciousness then generated dialogue among groups experiencing similar conditions, which creates solidarity and group cohesion. Each individual in the working class has the capacity to exercise his or her own voice, which is signaled by the tiny megaphone that each person is holding. However, when combined, all of these tiny megaphones create a giant megaphone equal in size held by the king at the top of the pyramid.

Through this giant megaphone that is comprised of many tiny voices, the working classes are able to send messages to all levels of the pyramid, especially those at the very top that are so far removed from the daily experiences of the working classes. If these combined megaphones fail to get the attention of those in power and generate change, then there will be a call to action. We chose to represent the call to action with protests, boycotts, sit-ins, etc; many examples of civil disobedience. The last element that we included before we ended the exercise was the faceoff between the workers and the riot police, who are entrusted to protect the property of those in power.

Outside of the course, I was able to further develop concepts and ideas about my own theory of social change. My model for social change does not look to drastically different from the one that we developed in class with the exception that I had the opportunity to add more dimension and depth. For one, I highlighted the role that media has in generating social change. For example, I do not call for a dismantling of the corporate media structure but instead focus on the reciprocal relationship that industry and citizen media should have, especially as a means to keep industry transparent and accountable. I also added the importance of the freedom of information, represented by a locked box where those in power often hold the keys to. In my model, access to information can also be a catalyst for action to generate to social change.

There were two main ideas in my own model that differed from the ones that we created in class as a group. The first is the idea that social change only comes through contestation between power structures and groups of individuals. In my model, I highlighted the importance of communication between diverse groups, which may be isolate by information bubbles. In this sense, the drive for social change steps beyond the pyramid model because I believe that communities should not only focus on institutions and power structures when determining how to improve their lives, but they should also focus at the local level. De facto segregation continues to isolate communities from each other, and I believe that a progressive model for social change should include not only the strengthening of community bonds within communities but also across communities. Embracing diversity, especially the diversity of ideas, should be central to a model of social change, so the protection of dissent is critical. Again, it becomes difficult to talk about this idea as separate from power structures, especially since industry functions around partisan dimensions, with labels such as “liberal media” and “conservative media” are normative.

The second major point that I added to my own model of social change was in regards to the intersection and interrelationship of social issues. For example, can we talk about de facto segregation in media ecosystems without talking about de facto segregation in society at large? Can we responsibly address issues of media literacy without acknowledging sub-standard education in low income communities and the defunding of public education?

Media plays an important role in generating social change, especially by bringing people together through shared experiences. However, in my model of social change I highlight the fact that the fate of media ecosystems are tied to the fate of societal ecosystems at large. Media ownership can simultaneously become a conversation about the distribution of wealth in society, just as the discussion about the access to media tools can become a conversation about structural economic inequality.

I am a firm believer that important steps towards social change , especially among low income communities and communities or color, lie in media creation. Self-representation through media is important, especially when your community is constantly being reduced to stereotypes and negative portrayals in the media industry. Also, if journalists are systematically misrepresented a community by only highlighting the negative, then I believe it is the duty of the members of those communities to seek alternative media representation, whether citizen journalism or otherwise. Furthermore, social movements have historically embraced different forms of media in order to provide counternarratives about their struggles, to build community, and to communicate collectively with those who would not listen prior to organized efforts. In short, media matters, and it is central to social change. However, it is important to remember that the role of media in social change is but one dimension in a complex web of interrelated social realities.

How does this model for social change relate to my intended final project for the Intro to Civic Media Course? Well, for one, it allows be to be aware that this model is a helpful guide, but it may not be representative of society or reality. In my own model, I debated adding the “media scholar” into mix, who is tasked with applying blanketing models about how media operates in society. Is it possible to avoid this? I am not sure. With my research on the daily media practices of immigrant communities in Boston, I hope to get an understanding of how people at large are thinking about where media fits into all of this. My hypothesis is that I will that consciousness and dialogue around social issues happen quite frequently, some of it through some form of media.