Photo Gallery: Bhopal’s Toxic Legacy

SIMONE KAISER / DER SPIEGEL The Bhopal disaster in 1984 was one of the worst industrial accidents in history. But almost three decades later, toxic waste is still being stored on the site under poor conditions. Here, the remains of the Union Carbide plant.

I’m here at the MIT Symposium on Gender and Technology, where I’ll be talking about the ideological affordances of algorithms. Our keynote speaker is Kim Fortun, one of the leading, powerful, and articulate voices in anthropology, STS, and feminist studies. Fortun has also been a driving force in driving the graduate program in STS at RPI, and has done a great deal of interdisciplinary teaching. At RPI, she educates engineers about social issues of the day and pioneers what is often called digital humanities. She was editor of Cultural Anthropology, transforming it into the widest read journal and developing web based components to the journal that are widely used as a teaching tool. She also moved the journal in the direction of open access.

Her first book, Activism after Bhopal, about the global chemical industry and the Bhopal disaster, demonstrated that it’s possible to do finely grained ethnography that merges with activism. Kim participated in the creation of Right to Know laws, which enabled public transparency about the possible effects of chemical industries.

Her new book, Informating Environmentalism, examines “how developments in information technology and culture since the 80s have played out in the environmental field, shaping how environmental problems are conceived and deemed significant, or rendered marginal.”

Performance Trouble: Language, Ideology and Expertise in Late Industrialism

Although Kim has never written about women and gender, feminist theory has been under the surface of everything she’s done.

Kim starts out by talking about the complex industrial infrastructure in our time, unregulated growth in those industries as they decay. She also draws our attention to two issues: big industrial disasters like the BP oil spill, and slow-moving disasters like asthma and the decline of frogs.

As we try to understand these issues, we need to apply a “kaliedoscopic mode of insight” from a variety of perspectives and frames. Fortun reminds us that she was in the field in India in the 90s, in graduate school at a time of particularly dymanic theorization, especially among feminism. She went to the field with a photocopied version of a pre-print of Spivak’s book.

It was an era of great hope that new flows of information could be transformative. And yet, she continues to remember an information board that people used to find each other following the bhopal disaster. At the time, Greenpeace and other organizations tried to make visible the kinds of risk that people were living under. Since then, Fortun continues to chase disasters, having looked at Bhopal, the BP oil spills, Fukushima, and Fracking.

At RPI, she puts her students into K-12 classrooms, charging them to create curriculum for students to see the world through a variety of frames. It’s much easier to get her undergraduates to think and feel these things themselves if they’re involved in getting other people to think about them.

Late Industrialism

Late industrialism is characterised, Fortun tells us, by incredibly complexity that lies behind something simple like a glass of water. Another characteristic is soiled grounds. Furthermore, infrastructure across the US is deteriorating. Many of it is more than 60 years old and unsupervised. We’ve also over-extended our systems, which are expected to handle new kinds of toxicity. We also have inadequate valuation systems to make sense of this situation. During late industrialism, we have seen a proliferation of high risk industrial activity.

Risky industrial activities have been exempted from many of the laws that regulate the environment. Although we have unprecedented data density, there are also serious gaps in data. Of 85,000 chemicals registered for use with the UPA, we’ve only tested a 3,000, and only 10 have ever been taken off the market. Furthermore, as climate change expands, we can expect a land grab of areas that become available as things melt.

In the face of this, people feel overwhelmed by complexity but lack faith in collectivity.

Expertise in Late Industrialism

Kim points us to marketing information from the American Chemistry Council (formerly the Chemical Manufacturer’s Association), who make huge efforts to advertise their interests and fund research that supports their industry (see the Atrazine story). Fortun argues that the language of industry supported science is often very essentialist, shutting down the voices of critics. In these spaces, it becomes very hard to make meaning outside the frame set up by them.

Kim also tells us the story of Baytown, Texas, whose motto is “where water and oil mix,” the site of the largest refinery in the world. In this town, the oil companies provide schools with their science curriculum.

Kim also shows us oil spill response plans as part of environmental audits by BP, ConocoPhillips, Shell, and other companies. Although they’re supposed to be reports about the individual companies, they’re nearly identical.

When expertise gets codified, it is often wrong. Fortun tells us the story a fertilizer distribution facility that blew up last April in Louisiana. There was a middle school across the street from the plant which was completely destroyed. 15 emergency responders were killed. The town had produced information about worst-case-scenarios, but they were the wrong ones, oriented towards fumes and spills rather than explosions.

Expertise can sometimes become too narrow. In the case of the BP oil spill across the US, companies were fully prepared for surface slicks, but not spills underwater. In the case of Fukushima, earthquake science predicted an earthquake of that magnitude in southern Japan. Anticipation of those earthquakes blinded people from the possibility of another disaster.

It’s hard to make sense of who to listen to in cases of disaster. There are so many apparently expert voices even on a question of whether people should be allowed to return to their homes. Another “wicked study problem” is an analysis that tries to attribute burden of disease from toxic waste sites in Idnia, Indonesia, and the Philippines that has lots of holes.

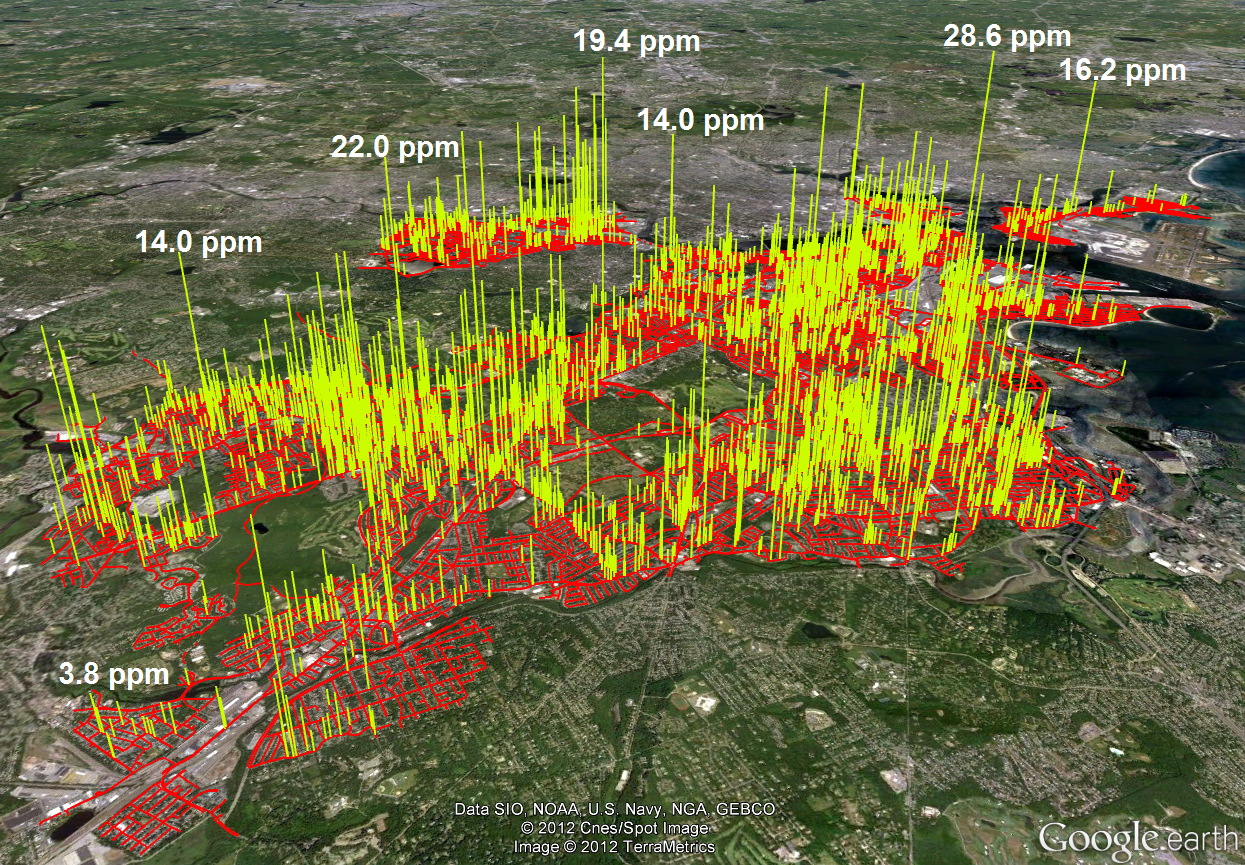

How can humanities scholars respond to these issues? Is it enough just to take down studies with holes? We want people to be doing this work, and improve on it, FOrtun says. She shows us a very cool study of methane leaks in Boston by Duke and BU academics.

Discursive Risk and the Side Effects of Calling Things Disasters

On one hand, greater surveillance gives us more awareness about risks, but calling things a disaster brings in the police and the power of the state.

We need to develop new frames of analysis carefully. Stories about unexpected, catastrophic risk can paralyze people in the face of that power. Late industrialism is a time laced with “discursive risk.” Kim tells us about John Casti’s book “X-Events: The Collapse of Everything,” a book that presents frightening failures in infrastructure.

Late industrialism is a time rife with double binds. We have emerging inventiveness and capabilities to make sense of things, at the same time that

Explanatory Pluralism and Activism

Kim tells us that to make sense of knowledge in late industrialism, we need to be mindful of the idea of the Subaltern, things which can’t be recognized within the dominant ideologies and practices of language. We need to understand the reality and advantages of “explanatory pluralism” (Evelyn Fox Keller, Making Sense of Life).

We need to find and create ways to find and invent ways to move in margins, between the lines and against the grain– to be aware of what gets left out, and move among it.

This may require us to develop new approaches to reason and rigour. One example is the project If It Were My Home, which allows you to overlay the boundaries of disasters on your own address. Fortun also points us to “An Unreasonable Woman” by Diane Wilson, an environmental activist. At a time when the importance of scholarship and intellectual work is being undercut from every angle, we need to be motivated by the very kind of scholarship that critical humanities people can put into the mix.

Our students are going to be responsible for the ethics of these systems, Fortun tells us, and we need to enable them to have the analytic capacity and the habits they need to keep asking good questions. Within our current educational system, there’s no pleasure in multiplying perspectives. That’s why Fortun makes her own students stewards of the habits of minds of even younger students, helping them “go into the world with fear and trembling”.