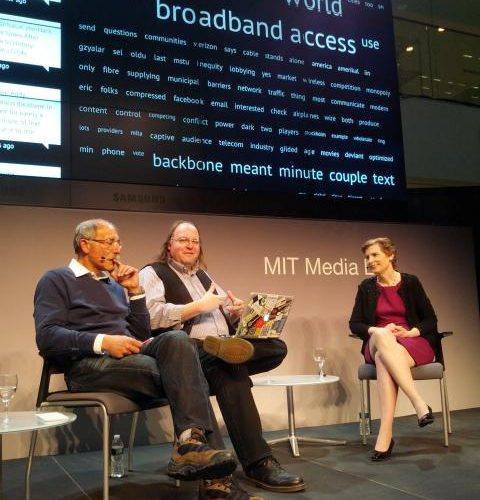

Liveblog of Susan Crawford talking about her new book Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age at the Media Lab Conversations Series.

Molly Sauter contributed to this liveblog, and Rodrigo Davies previously posted our transcription of the Q&A portion of the event.

Introduction and Biography

Susan Crawford was at the Media Lab today to talk about her new book Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age. She is a highly-respected lawyer and professor and has taught at Cardozo Law School, University of Michigan, Yale, and now Harvard Law School. She was on Obama’s transition team reviewing the FCC, and a special advisor to Obama Administration on Innovation and Tech policy. She is also a former board member of ICANN and founder of OneWebDay.

Susan’s Talk

Susan’s Talk

Susan’s core argument comes from comparing “connectivity,” in the form of wired and wireless broadband internet access to electricity, and that we in the US need to regulate it and invest in it like the important public utility it is. She begins by saying that 100 years ago electricity was a luxury. FDR’s fireside chats were inaccessible to some people because electricity didn’t extend far enough.

Now we see students trying to get their homework done parking in the lots outside public libraries to get WiFi and/or going to McDonald’s.

In the US, 100 million don’t have internet access at home. And 19 million have NO access to internet anywhere in their community. Internet access is too expensive. In fact, US internet access is much more expensive than most other places in the world, especially Asia.

Internet access is necessary for jobs, education, health care, …. Many Americans are suffering from second class internet service and paying too much for it. Currently, internet access is not treated like a utility, is not regulated.

How did we get here?

In the early 2000s, we had competition between phone and cable companies over who would provide Americans internet access. What looked to the government like a healthy market led to complete deregulation. However, the cable companies found it easy to upgrade their services to handle broadband internet provision at the end points, telecommunication (phone) companies need to replace miles and miles of copper wire with fiber in order to keep up with the bandwidth.

Leading up to this moment, we already had local cable monopolies in 96% of US markets. Verizon and AT&T are the phone monopolies and Comcast and Time Warner are the cable monopolies. Long ago, Comcast and Time Warner sliced up the country into markets that they would each control. They are facing almost no competition on the wired side.

Verizon FiOS — a fantastic service by Susan’s account — has emerged as the only competition to cable’s dominance on broadband internet. However, in March 2010, Verizon announced they were no longer going to expand beyond the small patches of the East Coast they were serving. Comcast serves 18 million American customers across a market of 50 million in its footprint covering about 45% of the US. Verizon FiOS’s footprint only overlaps with 15% of that market. The bare competition means that powerful market actors like Comcast can raise prices with little pushback.

[The regulators are aware of these issues, as many statistics Susan cites statistics come from the FCC’s own 2010 National Broadband Plan report.]Right now, 82% of customers have their internet access need met by ONE technology — cable — and 9% of Americans are left with nothing. “Cable is pretty much a monopoly now.”

Brian Roberts is the CEO of Comcast, concedes himself, “We have one competitor.” It’s Verizon FiOS. But Comcast is now colluding with Verizon to sell each other’s services.

Wireless isn’t much better. Verizon and AT&T comprise the wireless duopoly.

Two-thirds of Verizon’s revenues come from wireless. Verizon sold off a lot of their landlines. Susan tells an anecdote about her mother, who was still using her old DSL connection here in Cambridge and struggling to get service on it.

Wireless service revenues per capita are much higher in the US than in Europe (almost double). Susan says wireless service is more competitive than wired service in America, but only by a bit.

Furthermore as we look to criticize these companies or share concerns about net neutrality, these companies argue that they have first amendment rights like any citizen and have the right to edit what goes out on their services.

What we should do

We should be ensuring that cities can take care of connectivity for themselves. Ideally, this would be through commissioning their own municipal networks. In some states, laws have been passed to make this impossible at the municipal level.

Where we have networks, Susan argues they should be open. The ideal formula is open, connected, and ubiquitous networks. To achieve this, we need to lower barriers of access to capital for competitors to build fiber access in cities. Susan suggests that perhaps states can be sources of this capital.

Their is possible opportunity in an impending scandal in California where rural calls are struggling to be competed across the state.

A major concern for Susan is the recent merger of Comcast + NBC Universal. This creates a conflict of interest, where the common carriage service can determine what is carried and could privilege its own content. What do we do when Comcast wants to implement bandwidth caps on content that is not it’s own?

Susan wrote her book to get these issues on the radar screen. Right now it’s unthinkable to do something about this in Washington, DC.

Susan argues that having oversight is a pro growth, pro free market, and pro innovation step. It would unleash a lot of capital that is being otherwise stymied right now. Regulation sounds like red tape but it can function as the exact opposite.

For Susan there is an electoral strategy here, she wants us to understand how bad the situation is and elect people that are going to do something about it. People that will answer the question: “What are you going to do about fiber access in america?” We need to get to a point a point where you can’t hold elected office unless you can wrap your head around these issues.

South Korea makes Susan feel like she’s living in a slow, rural place with sparse access to internet. Coming back to America is like taking a rural vacation.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. More than 240 places around the US working on municipal network projects. (Again, see http://www.muninetworks.org/communitymap.)

Coming back to electricity, Susan comments that it was good for more than street lamps, which we didn’t see until the worlds’ fairs of the early 20th century. Those fairs were sponsored by those electricity companies. We don’t know things until we can see them. Perhaps we need the visual of high capacity networks in America before we can make progress.

You can think of wireless as an airplane flying outside, but airplanes need runways. They need to attach to wires. But there is no plan to update to fiber. We are stuck with Cable and companies have no incentive to upgrade right now.

Here’s the big picture: when we flick on an electric light, we take it for granted; “we should be able to take connectivity for granted too.”

Susan’s book and talk is meant as a call to action. She wants us to be happy warriors battling for the telecommunications networks we deserve. “This is ridiculous that we are in this situation.”