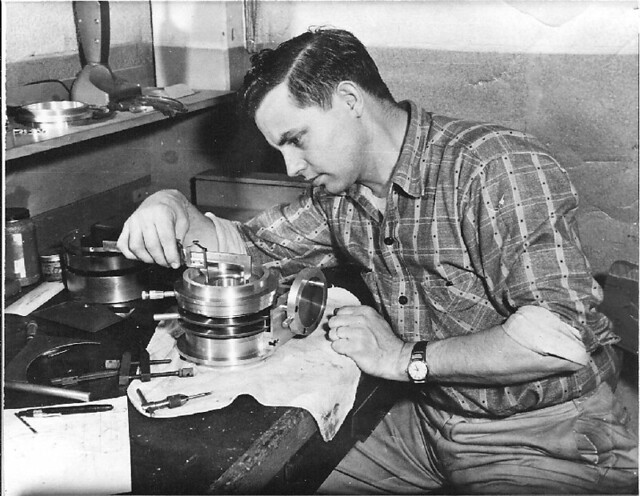

My mother’s father was a machinist.

He had a stocked workshop, and I can’t picture him without a blue jumpsuit on, speckled with the light-brown — a sugary scent — of machine oil.

Even as cigars browned his fingers and arthritis froze them, he worked with his hands. His father, an Iowa corn farmer, did too.

My grandfather, who gave up farming after a $12 profit his first year, did amazing things working with his hands. He helped one of the 20th century’s great inventors, Jacob Rabinow, create the first mail sorting machine that could read zipcodes and barcodes. (And in a tie-in to MIT that I love, Rabinow was recipient of the Lemelson-MIT Lifetime Achievement Award.) But, by all accounts, my grandfather was a different man when he couldn’t make things professionally. Arthritis forced him to retire on disability at 40. “If he held up his hands and fingers,” my aunt told me, “there was no space between the fingers. They couldn’t even be bent at the knuckles.”

That didn’t totally stop him. “Dad made his own fishing rods and fishing lures,” my aunt went on. “He repaired/maintained our boats and cars, and made parts for just about anything he was working on (including engine parts). Also, canvas covers for the boat and car parts; he had his own special needles for Mom’s sewing machine.”

So while the term tends to be associated with the casual hacking of the physical, non-digital world, my mother’s father was a maker.

He passed when I was young, about two months after driving from Iowa to DC, palms-only on the steering wheel of his motor home, (terrifyingly) clinically blind, to be at my mother’s wedding. I didn’t have the time to learn from my grandfather anything like making. Catching catfish and Chesapeake Bay rockfish, yes, but not his machinist’s tools and craft, and certainly not, if it could have been taught, the skill of looking so good at 20 (at left).

He passed when I was young, about two months after driving from Iowa to DC, palms-only on the steering wheel of his motor home, (terrifyingly) clinically blind, to be at my mother’s wedding. I didn’t have the time to learn from my grandfather anything like making. Catching catfish and Chesapeake Bay rockfish, yes, but not his machinist’s tools and craft, and certainly not, if it could have been taught, the skill of looking so good at 20 (at left).

My father’s father (below, at right) delivered mail — the mail sorted by my other grandfather’s machine. Because his day was done when he finished his route, the job gave him time to work in a small shed, where he kept tools and a workbench, but they took him only as far as many people get: he knew enough to repair, maybe to frame a new room, and to cheat me at wiffleball by gluing a broom handle inside the plastic bat. But not, as far as I remember, to build something from nothing.

By the next generation — my dad’s generation — makers in my family were harder to come by. Their spirit and skills, in those years, still had to be passed from one person to another, personally. If that chain was broken, it was tough to relink. I told myself the maker gene in my family was gone.

By the next generation — my dad’s generation — makers in my family were harder to come by. Their spirit and skills, in those years, still had to be passed from one person to another, personally. If that chain was broken, it was tough to relink. I told myself the maker gene in my family was gone.

I told myself I didn’t have much material to work with.

I told myself it didn’t matter.

I told myself all of that. Until last fall.

The memorial for my dad’s dad was in Barnesville, Pop Pop’s hometown, a dot in eastern Ohio.

My dad says that when he was sent to stay with his grandparents there for the summer, he and his brother (at right) had nothing to do but throw dirt clods at passing coal trains. And when politicians today talk of remaking American manufacturing to save small-town America, Barnesville illustrates how it’s more than just job training and tax breaks. Drive I-70, our country’s oldest interstate. At one end, the Rockies; at our end, just west of the Ridge-and-Valley, are water-logged hills called the Appalachian Plateau. Enter Ohio from Wheeling, and there, worn down, are earth-mover runs and coal elevators, abandoned.

My dad says that when he was sent to stay with his grandparents there for the summer, he and his brother (at right) had nothing to do but throw dirt clods at passing coal trains. And when politicians today talk of remaking American manufacturing to save small-town America, Barnesville illustrates how it’s more than just job training and tax breaks. Drive I-70, our country’s oldest interstate. At one end, the Rockies; at our end, just west of the Ridge-and-Valley, are water-logged hills called the Appalachian Plateau. Enter Ohio from Wheeling, and there, worn down, are earth-mover runs and coal elevators, abandoned.

Yet, you enter Barnesville, and suddenly there’s this mix of rachitic houses next-door to wholly remade Victorians.

There in eastern Ohio, natural gas has supplanted what’s left of the coal industry and stirred the town’s hibernating trades. There’s cash now not just for new roofs and frames but for time, time for ornamentation, for craftsmanship — time for learning from others how to do it. There are the perils of natural resource-driven booms, but for the first time in decades, Barnesville has time again to make.

It was seeing this that opened me to the possibility that my recessive maker gene might, in fact, have an expression — more than other powerful influences, like hanging around MIT…more than when my step-dad showed me where to hide pennies in a Cub Scout pinewood derby racer to bring it within ¼ ounce of legal weight…more than when my best friend and I duct-taped a toboggan to a skateboard, bobsledded down the driveway, wrecked ourselves over the edge of a 10′ retaining wall, and got up and did it again.

Instead, here’s what sealed it…

Pop Pop left me the family’s grandfather clock, handmade by my grandmother’s brother, Bob King.

Here the clock is in my Pop Pop’s house…

…and where it stands now in mine:

Uncle Bob is a hobbyist woodworker. He made things in his spare time, loved making, learned it from others, shared it with others, and did it well. He handmade the frame and casing of that clock and gave it to my grandparents on their anniversary. When my grandfather passed and left it to me, Bob — after the memorial, as my cousins and aunts could be heard divvying up family photos, furniture, and letters — described to me the history, the reason, and the how of making that clock for his sister and brother-in-law.

Here are a few moments from that conversation among Bob and others, including my dad and me:

This handmade clock and Bob’s voice moved me from “I’m destined to get a screwdriver stuck in the closet floor while running speaker cable,” as my dad once did, to “I might be able to make”.

But without that access to other makers, learning to make would be impossibly hard. I needed to know how to make something out of nothing, from someone I couldn’t learn from in person.

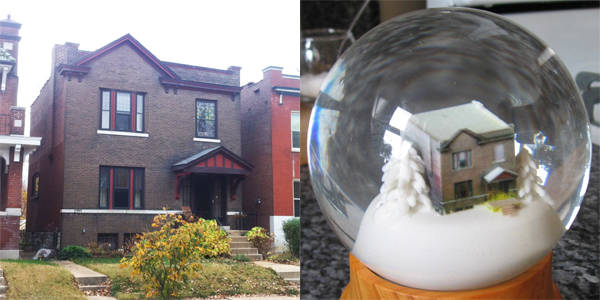

That’s when, the day after my dad dropped off the grandfather clock to my house, a post appeared: “HOWTO make a custom snowglobe of your house”.

My wife and I moved into our house last year. We don’t quite buy the idea that homeownership is inextricably part of the American Dream, but since we weren’t Massachusetts natives, a house meant roots here, a place to call our own, and responsibility: an 85-year-old house that you own creates for many people the strongest tie to a physical thing they’ll ever have.

So when the post appeared and with my wife’s birthday coming a few months later, there was a thrill that I knew what to get her…and a terror that the how-to took CAD experience for granted: “I want to make this because of how much our house means to her, but even with these plans, I have no idea how to make it.” Through January, February, and March, I struggled, trying to learn Google SketchUp, muddling along, alone, and failing.

I needed help. I needed a human how-to. And it came in the form of our broad definition of civic media: making something that binds people together, through information.

This video is from Marcus Ritland, who introduced himself to me on the Shapeways 3D printing forum. Think, as you watch it, about what’s happening. I’m trying to make something and failing. Shyly, I put out a call out for help. And Marcus, without asking anything in return, creates a 14-minute personalized tutorial.

It’s a great model for civic media: a community member finds a problem and asks for help, and through media, another member creates a clear, shareable, adaptable solution. The exchange creates a recursive civic, rather than financial, debt. It’s a model that researchers like our own Sasha Costanza-Chock are applying to physical communities: much civic media, such as newspapers, don’t and can’t efficiently connect community problems to community solutions, let alone in a way that’s self-reinforcing. We need to identify or create civic technologies that do.

My experience in Shapeways and through Marcus meant the concept of how-to went from a static model — looking for information distribution based on schematics — to an adaptable model featuring direct, community-building, resilient generosity.

This generosity, like my great uncle Bob’s, becomes the communicable disease we call philanthropy. Why “disease”? You’re not supposed to want to give things away for free. I’m not supposed to want to make things myself when I can buy them. I start wasting my Tuesday nights in Arlington High School’s woodworking classes, learning from volunteers how to use power tools, exchanging plans with my neighbors. I blow my weekends soliciting how-to’s from folks online and, worse, making things with them.

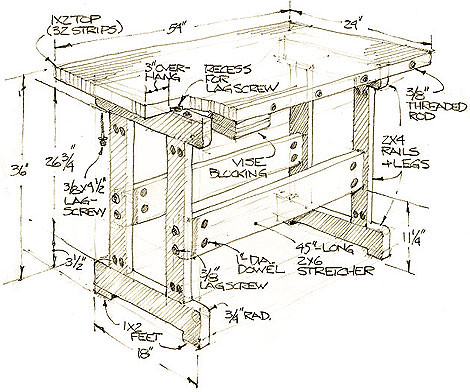

Like a workbench…

…based on this Popular Mechanics design but personally walked-through by Arlington High School’s shop teachers:

Or a headboard and bedside tables, built on that workbench, over many weekends, tentatively, with countless beginner’s mistakes…

…but with the tables designed by a blogger who explained every small step using her diagrams made in SketchUp…

…which were made to be adaptable: with a click-and-drag, I could resize them for our space.

And a window seat/storage bench, with my better and better skills, built, this time, in just a day:

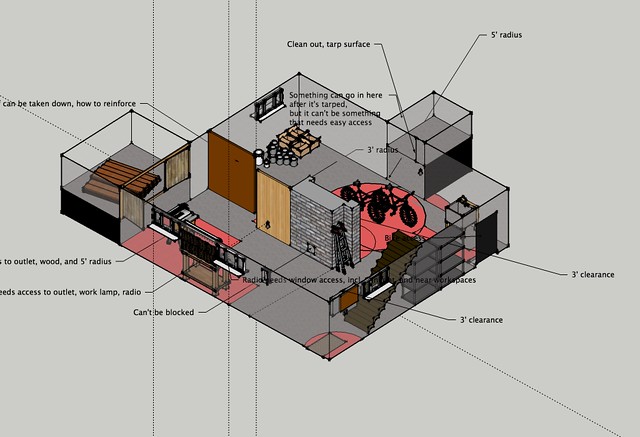

And my disease getting worse, redesigning my entire basement…

…so that I knew where and how to place my wife’s and my tools:

And a grill patio and flagstone path, not so much for their “makeriness” but because I got to build it with my dad.

And Marcus, whose video and 30+ emails in reply to my 30+ questions, led to the perfect birthday present:

Unless quickly isolated, this philanthropic disease is communicable, chronic, and incurable. I get twitchy now when I don’t have a woodworking project to do, learn from, and teach others. Many have the disease. My 80-year-old nextdoor neighbor, a retired plumber, sneaks into our house to fix things and shows me later how to do it myself; he’s given me his 1940’s leather-bound collection of handyman books. I’m about to teach my aunt how to redesign rooms using CAD. My friend up the road has a key to our house so he can use my table saw whenever. And whether my wallet likes it or not, I know every employee with a Saturday shift at Rockler Woodworking, Wanamaker’s, Hillside, and Shattuck. I visit them every chance I get, no matter what:

I have a long way to go. For now, if a woodworking project isn’t entirely right angles, forget it. A Saturday morning trip to Wanamaker’s to get a new drill bit necessarily means an afternoon trip to get the correct drill bit. Asking advice means explaining what I’m trying to do and knowing the names for things, and most of the time I have no idea.

Or put it this way: I won’t be inventing my generation’s barcode reader.

But that’s not the point…

The rhetorical and financial structures of how information was shared last century were an exception. They’re ceding their gains to broader, more diverse, hacked-together forms, which tend to combine older values with very new technologies. Bob King valued something — working with his hands and passing on his lessons — and I got to build upon it and spread it using a new technology: his explaining how he made the clock, my recording him, and, now, my sharing him with you. Likewise, I had just wanted a template I could use to make my wife a gift, but instead I was taught how to adapt the tool to my needs and how to teach it to others.

Like media’s own evolution, there’s a move away from the misguided, almost misanthropic ideal of a manual for building communities around information.

Instead, we get to say, as my grandfathers did, “Somebody out there must have had a problem like this. Let’s ask. Let’s mess with it, work with them. I know we think we’ve got nothing, but let’s make something. Let’s get our hands dirty together. Let’s get some grease on our clothes. Let’s try, and let’s fail. And, God help us and let us keep our fingers, let’s now be makers.”