What makes someone put themselves at risk for an abstract idea, say, like freedom, a better future, an imagined utopia, an ideal? And how does this one person come together with other and become many? How does a movement start? What are the factors, catalysts, that make an action significant and pushes many more?

Who knows, really.

However, our Intro to Civic Media class tried to approach an understanding of some of the basics that are the building blocs of a movement. We tried to identify, through our different readings and an exercise, some key characteristics that might be common factors in a model of social change.

Malcom Gladwell, in his New Yorker piece “Small Change: Why the Revolution will Not be Tweeted”, argues, as the title suggests, that technology in itself does not make a movement. While some believe that with “Facebook and Twitter and the like, the traditional relationship between political authority and popular will has been upended, making it easier for the powerless to collaborate, coordinate, and give voice to their concerns”, Gladwell states that other elements have a bigger part to play in social activism. Through the example of the Greensboro sit-ins during the Civil Rights era in North Carolina, he makes the case that instead, someone is more likely to join a movement because of the following:

-degree of personal connection to the movement (how many people already involved does the person have strong ties to?)

-degree of risk versus degree of repression (how much are you standing to lose if you participate, or how much would you lose if you don’t?)

-cost of participation (since most activism that actually challenges the status quo is dangerous, people then need a pretty strong reason to participate)

and the movement will be successful if there is:

-training and organizational network and support

-a centralized and hierarchical power structure

-resources (money, other)

-a geographic center (or many) where people could gather to communicate and coordinate with each other (like the Occupy movement?)

Gladwell says that social media, on the other hand, are tools designed to develop connections with people you would not otherwise be able to, and because of this, they are intrinsically weak. And that also, most people use social media as passive activism, where a person might participate in a call for action, as long as it does not involve too much work. However, in my opinion, though maybe in a general sense some part of these statements are true, it would imply that everyone uses social media in the same way and are not capable of appropriating it for their own creative purposes. As a couple of our classmates suggested, even civil rights activists used phones (through phone trees) and the latest technology of the day in creative ways to propel their movement.

However, these are only tools that can help push it forward and are not the key ingredients that created it. And from what I know, no one in the day called the civil rights movement the “Phone Revolution”. Yet, perhaps, it is possible that these social media tools actually facilitated the infrastructure to organize thousands of people that could not do so in other ways without getting repressed by the state or without cultural barriers possibly impeding the ability to coordinate actions. Or, if not, at the very least, it allowed activists to show their own version of events, which brought an out pour of international solidarity and pressure.

“Social networks are effective at increasing participation — by lessening the level of motivation that participation requires,” Gladwell states. So, in a way, it is true that people might not put themselves in the line if it is something too difficult to do, but it also opens up the possibility of providing support for a movement, at least from the margins, and there is some value to that as well.

One of the points that Gladwell also tries to make is that a movement cannot be successful without some type of centralized hierarchical process in place to provide discipline and set goals. Without it, a movement is rudderless, he believes. But Lina Srivastava retorts (via Stefanie Ritoper) that “he shouldn’t be so quick to discredit decentralized, horizontal movements” because there have been movements (underground railroad) that were decentralized and non-hierarchical even before social media, and social media has allowed for successful organizing (DREAM Act student activists).

Yet Ritoper put it best when stating that social media is just a tool: “People organize people. The heart of good social change work is in good face-to-face relationships, through sharing stories, building trust and exchanging skills.” And if social media, and other technology, is used to facilitate and enhance this process, then it would be aiding in pushing for social change.

This message is reinforced by Christian Fuchs, though in a different context, yet with similar implications. He writes that media reported on “social media mobs” with the UK riots that happened this summer, giving too much credit to the tool for causing the violence, instead of the social conditions, actions from police, and reactions from the youth that stirred the whole momentum. People do not do violent things just because someone text them to do so on a Blackberry, but because of perceived injustices. As Fuchs suggests, unemployment, inequality, economic conditions produces the context for a person to be desperate and prone to violence. This context, however, as shown by the Occupy Wall Street movement, can also be the catalyst for people to demand social change and join a movement to do so.

So taking all of these factors into account, we began the exercise that Gabi Schaffzin facilitated:

We first identified, from the different readings and our own observations, elements, binaries and other key aspects that would be essential in determining the level of participation within a movement, and this is what we came up with:

-tie strength (personal connection to the movement)

-degree of risk vs degree of repression (as mentioned before, how much you would stand to lose if you do or do not take part of the movement)

-Centralized vs decentralized (is the organizing done through hierarchies or networks?)

-Physical proximity

-Granularity, or unit of participation (Sayamindu described this as how much effort you put into your activism – liking something on facebook versus resisting arrest)

-Income (or social) inequality

-Cost of participation

-Identification with movement (sharing of values)

and… Pluck

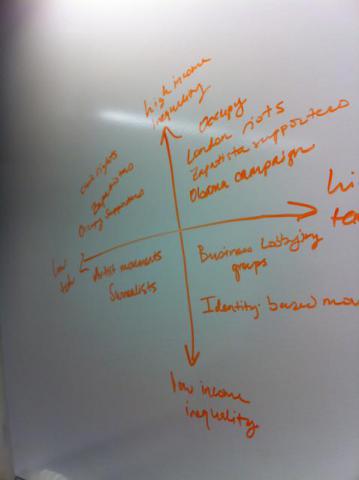

Then we split into four groups of two, and our task was to create a matrix that would establish a ladder of engagement of different examples of movements with the constant variables of low tech and high tech measured in relation to one of the key elements above, to help us visualize the different manifestations and evolution of movements.

The following chart (all photos provided by Gabi!) tries to show different examples of movements in relation to different levels of social inequality:

In the upper left quadrant (Low tech and high income inequality), we used the examples of the Zapatistas, the Civil Rights movement and Occupy supporters in this category. In the lower left one, we used art movements and Surrealists (still a movement, but not one determined by income inequality), and so on.

You can see more graphs attached! (sorry, I was going to try to relate the interpretations we presented for each one, but I did not write notes for any of the graphs)