What group of people do we hardly ever listen to, but hear about all the time? Question Bridge is a project about the radical power of asking a question, and then listening to the answer.

Question Bridge is a project to allow black males to self-define their community for themselves, but Chris Johnson has found it relates to common issues relevant to all of us. Communities often find deep divisions and fissures, and the people on each side of the divide find it hard to communicate across the chasm. In the black community, one such divide is between youths and elders, the hip hop generation and the Civil Rights generation.

The statistics in black communities are at a crisis point, no matter which numbers you look at. As just one example, in 1950, 77% of black children had 2 parents. Now it’s 38%. Then there’s the participation gap, the achievement gap, and other gaps plaguing the black community writ large. But there are also solutions in the community, so how do you get at those? It begins with a process of asking questions.

Asking a question is a deceptively simple act; It communicates to the person you’re talking to that you don’t know something, and it sets you up to listen to their answer. And there’s another layer of within demographics that’s very different than what goes on between demographics. There are issues that exist only within the black community, like skin tone, that are phenemonoligcally racist, and that only get discussed when you hold conversations from within.

Black males are frequently talked about and depicted in the media, but rarely in a self-defined way. The team prompted black men to ask questions they’ve always wanted to ask other black males, especially those who aren’t like themselves. They gathered footage from 160 different men from 12 cities across the country, and then sought individuals who could answer the questions they had received. Questions like:

- What do you fear?

- How do you feel about the N-word?

- What do you have in common?

- Why do I need to get a job?

There are multiple answers to each of these questions, all with legitimate places in the dialogue. Some of the questions are iconic, and are embodied by young black males in cities across the country.

Question Bridge is deliberately an art piece. It’s been at the Sundance Film Festival, and will soon be at the Brooklyn Art Museum [go see it!]. Many of the transformative moments in our history could be considered art, Chris says. The rebellion in Syria was started with graffiti. Ghandi’s grand performance was the Salt March. Rosa Parks, on the bus in Montgomery, Alabama, was a planned performance.

Chris and Bayeté employ recursion in their work. In art, being predictable works against impact. You need an element of surprise to gain attention. What happens when you translate powerful social issues into an embodied form that people can identify with, because the issues are no longer in the abstract? “A piece of work that articulates social issues is like nothing else,” Chris says, and the translation of this process into actual policy is the next step. A face of this project is directed at the public, but part of it’s also targeted at the art world, so that artists can do work that is not just beautiful, but also useful.

Question Bridge is a trans-media project: it’s art that’s good for art’s sake, but it is also useful and accessible in people’s everyday lives. There’s a gallery version for museums, a single channel movie version where you can view all 5 screens on one projector for screenings, an educational curriculum, a mobile app, and a searchable website with an index of questions, answers, and self-definition through tagging. The mobile app presents you with a question, and you can use your device’s camera to answer the question and add it to the database. You can then go online and see the other answers to the same question, and see where you fit into the broader conversation. The idea is to take these conversations out into actual communities, because museums are still coded places.

What group of people do we hardly ever listen to, but hear about all the time?

Question Bridge was inspired by a performance piece by Suzanne Lacey, world-renowned performance artist. She goes into communities and researches the critical social justice issues embodied in the community, and creates theatrical performances around them. She came to Chris’s school as a dean, and they collaborated on “The Roof is On Fire”. They tried to generate a media literacy campaign for schools, but in talking with kids, realized that the kids actually have a sophisticated understanding of the issues they face. But as soon as the students leave school, they become “black kids,” and behavior and attitudes towards them change.

Lacey confronted this problem in a performance piece, where the kids hang out, talking in cars with each other, and the audience is granted access to eavesdrop on the intense conversations they have. An audience showed up and proved that you can radicalize the act of listening.

This piece moved Chris from the fine art space to performance art. Listening to someone speak is a gift. So, he thought, if listening is a passive way to be very generous, what’s a more active way? Questioning.

We watch clips from the Question Bridge video (1996):

A young black male poses a question to a video camera: Why do I need to act, talk, and look white to get a job?

The video clip is shown to older black males, who answer based on their life experience

Answer 1: The subordinate group always has to take on the dominant group’s mannerisms.

Answer 2: You are making yourself attractive to the industry in which you are working, not so much white people.

Another question: Let me ask you a question: Who do you think you are? Why do I need a job? You don’t know me.

Answer: You’re right, I don’t know you. I don’t need to to respond. I’m a child of God (among the many things I am), African American woman, attorney, many things. In terms of your relationship to your creator, that’s what you are too, and defines what our relationship should be. You need a job because we all have to eat and sleep. I don’t know anything free in America yet (maybe sunshine — but they charge you for that in southern California, too). You’re going to have to take care of yourself, which will require money. That’s why you need a job.

Question: Have you given any thought of where the money comes from for public assistance, and do you care?

Answer: I’ve thought about it. I’m on public assistance. We do go out and look for work. We can’t work as long, because child care is really up there. I pay $300/month for child care. We do have people who take American jobs who aren’t taxpayers, because they’re not American citizens. People get grants to start businesses, but we who already live here don’t get the same respect. There’s only a small proportion of people that get on public assistance to not have a job, but you only focus on that small proportion.

At first, Chris resisted the narrow scope of focusing on black males, because black women added a whole lot. But something special does happen when black men ask questions amongst themselves. Instead of prescribing what the division is, they let people ask whatever they wanted, which brought out many very different dimensions than could have anticipated.

Included on the list of cities the team visited for the Question Bridge project is San Bruno’s county jail, where they sought answers to questions about committing acts of violence. To get permission to videotape the interviews with black males in jail, Chris first taught meditation at the facility for an entire year.

There was a clear decision not to use text questions and answers.When you present a video of yourself saying something, you’re accountable in a different way. Question Bridge is about embodying what happens when two people talk to each other in first person.

The framing forces you to compose yourself something like the way you do it in the world. You can’t talk shit from the safety of your computer. But also, you can see the understanding and even the hurt in older respondents eyes as they do their best to answer challenging questions from the youth.

Another clip from Question Bridge:

Young male: Growing up, I’ve seen black people who made it out, and changed who they are.

How has your financial success or educational success compromised who you are on the inside, or who you want to be?

Older male: I feel like I compromised my membership in the black community. It’s as if it’s a zero-sum game: the more successful a man becomes, the less people in the community embrace him. Success makes you “other”.

Example: the soul shake.

I remember the day I stopped doing that. It was on the courtyard at Harvard where I started giving my friends the corporate hand shake instead of the soul shake. And then at the hospital where I worked, I gave all my friends the corporate handshake. Until one day, another doctor came up and what does he do? He gives me the soul shake. The moral of the story? Don’t try to be black, be yourself, and you are black.

Another man tries to explain that putting on a suit to go into a [white majority] corporate board room is like a knight putting on a shield and suit of armor before riding into battle. The boardroom is a coded environment, and it’s battle, and you need the right tools to succeed there.

A third man says that success hasn’t changed him at all, but it has changed the perception of him. And the practice of disowning successful individuals, of deciding that they’re not “black enough,” has created a dilemma in the black community, because when someone succeeds, people decide they no longer belong to their community, but some other.

Another man responds that “When we get into a position of power, we make people uncomfortable. On the other hand, there are ways you have to be. There’s a difference between adapting to hostile environments, and ceasing to be yourself.”

“There’s a thing called “maturity”, which is undervalued, due to “ghetto-centricity,” the idea that the ghetto is central to all black identity.

The truth is that everyone evolves, no one stays the way they were in 1920. We need to be in a process of evolution; there’s no ultimate blackness, ultimate street credibility. There’s who you are now, and who you’ll be come next. Keep adding on top.”

Related Projects

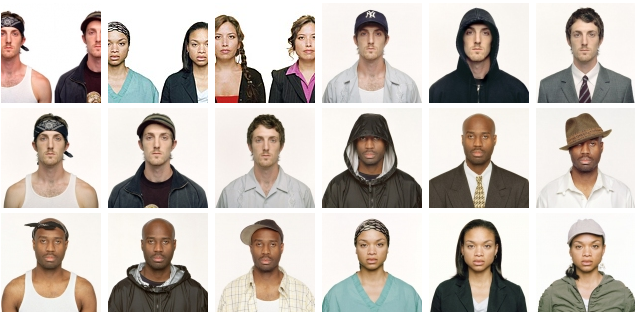

Bayeté Ross Smith introduces his photography work, including an exhibit entitled Our Kind Of People. The title’s inspiration comes from the iconic book about the history of the black elite class in the US.

Each of us has multiple personas within us, and we express it to the world through clothing, appearance, and fashion. Bayeté controlled the lighting and facial expression, and the viewer is left to the respond to the combination of the person’s face and their clothing. Bayeté found that different clothing, from hoodie to doo-rag to business suit, could drastically alter how people perceived him.

The effect is that the viewer internally realizes that black males, and indeed, any of us, aren’t solely one identity.

Hank Willis Thomas, another artist, and graduate student of Chris’s, produced Winter in America, a stop-action animation starring action figures from his childhood in a reenactment of the murder of his cousin. His cousin had happened to be with someone who was robbed for a gold chain, and it cost him his life.

Kamal Sinclair, a biracial playwright, dancer, and mom, came in as a grant writer and decided to take on the challenge of translating Question Bridge into a curriculum, which is now being piloted in schools in Brooklyn.

Questions and Answers

Q: As an art piece, what’s your role as curator, in defining which questions/answers are broadcast?

The questions posed were organic, with a simple prompt: You know there are black males not like you. What do you want to ask them? The team then curated which questions to feature, and found black males who could answer them, based on life experiences.

Q: How did you decide what to give people?

People who are marginalized live under a cloud of questions, and are rehearsing under those questions, and when you give them an opportunity, they speak, and are empowered by the opportunity. Questions were chosen on the spot, by intuition. We tried to get general questions answered by a cross-section of demographics.

Q: You’re doing this as an artist, activist, educator, teacher… it sounds like there’s a real goal.

What’s the ideal you’re after?

Chris: I’m not a journalist. 🙂

But I am. 🙂

I’d say my hope is to change the way people think about black male identity, and consequently people with other identities as well.

Q: Expansion plans?

What about doing one for black women?

A: We ask people who aren’t black men to be a privileged witness to the process. I’ve heard many sisters say, “When do we get a chance to speak?” One thing I want to do is bring this process (not with me doing it) to the Native American community. There are all kinds of things — living a tribal life, or not — which could percolate to the surface.

The reality is, this is a large undertaking, and we’re still working on bringing this version to completion. There’re still things we want to do with the website, community engagement, etc., that are expensive and take time to complete.

Q: Did you ever interview really young people?

I’m thinking of a 13 year old nephew struggling with some of these issues in public school.

The youngest was 8, oldest was 84. [shows clip of adorable little boy asking, “When do you know you’re a man?”]

Q: How has the curriculum been working?

Have you targeted after school/in school settings?

Since we aren’t an education organization (though we do have education experience — Chris has been a professor for 34 years), we worked on designing the curriculum to be adaptable to a lot of different settings. We did some work to align it to core standards (high school), which enabled us to most easily collect data. It was piloted in Oakland, Brooklyn, and the International Center for Photography.

So far, we’re just at the tip of the iceberg, getting it going. It’s complicated to deal with school bureaucracies. It’s obvious for African American male achievement programs; but we feel that mainstream classrooms need this as much as those programs do.

Charlie DeTar contributed to this post. This is a liveblogged post of our Civic Lunch. Join us for future events!