Yesterday, Matt Stempeck argued that non-profits and civic organisations need to embrace failure. While I appreciate his point, I think that failure is poor teacher. I agree with Jason Fried that learning from failure is overrated in the startup world, and that success is the best teacher of all. As a result, I tend to prefer practices which grow the capacities of people more than a body of knowledge about what works and what doesn’t.

Matt argues that non-profits need to accept and publicise failure in order to learn. He wants non-profits to be more like Silicon Valley startups. He also wants foundations to be more like angel investors and venture capitalists. He argues that high value projects require risk-taking. We should not penalize people who are willing to take those risks, even when they fail, since failure is common.

Matt’s argument in favour of fail aims to promote good risk and limit foolish risk. If people are made to feel comfortable admitting failure, it may become easier to retire lukewarm projects and try something new. New projects might also learn from the mistakes of others, especially if advisors and board members have received a clear, honest retrospective on the failure of past projects.

These are admirable values, coming out of Matt’s deep experience in the non-profit world. I agree that penalizing failure discourages good risk-taking. But failure can only teach us so much. I also think it’s unlikely that documenting failures will help new projects learn from failed ones. In the worst case scenario, the pile of lessons accumulated by a funding organisation can also create a burden that stifles the potential of a new project to innovate. Although we ought to learn from failure, I think that we can learn much more from the experience of success.

Learning from Failure or Success

Ernest Shackleton’s world-

famous fail: The Endurance

you won’t make the same mistake twice, but you’re just as likely to make a different mistake next time. You might know what won’t work, but you still don’t know what will work. That’s not much of a lesson.

— Jason Fried, “Learning from failure is overrated”

When I first read this blog post by Jason Fried, I hated it. It sounded arrogant, snobbish, and hubristic, the opposite of who I want to be. But when I reflected on my own experience, I had to admit that Jason is right.

I have been lucky enough to be part of several successful startups. My first charity completely failed to reach our aims, but I have also been part of a successful one. In the tech startup world, I have been part of three modestly successful startups within a loosely connected circle of highly capable investors, techs, and entrepreneurs. When I think of that circle of colleagues, I can identify capabilities which were essential to our repeated success, things I never could have learned through failure.

What are those things? To start, look at this great post by MobileActive on the Failfaire site, about top failures to avoid in Mobile for Development:

- Don’t clearly state the project objectives

- Don’t plan ahead

- Go it alone

- Don’t adjust / don’t compromise

- Ignore the community

- Don’t scale your rollout

- Ignore critics

- Burn your budget

- Burn bridges with other orgs

- Don’t plan for the fund

While I broadly agree that these patterns should be avoided, I have two problems with this list. Firstly, their emphasis on consultation and diplomacy discourages the kind of risk-taking Matt Stempeck likes. Secondly, the warnings are not atually very helpful.

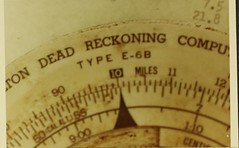

Dead Reckoning Instrument from a crashed Ryan Brougham. Do you want to learn from this pilot or from Charles Lindbergh?

MobileActive’s advice might prevent me from rushing into an ill-conceived, poorly-executed project. But none of it will help me run a successful project well. It’s hard to know when you’re in a failure mode, especially in categories like planning ahead and going it alone. Furthermore, while past failures can teach me that I should plan better, that awareness doesn’t necessarily evoke the capability to plan well. If I burn through the budget ahead of expectations, I learn that I should do better at budgeting. That failure probably won’t teach me how to make and execute a great budget.

Nuanced learning from failure often involves chancy counterfactual reasoning. I have long given up asking “what if” about former failed projects. I sometimes theorize what I might do differently, but I try to avoid speculation on outcomes.

Earned success is a much better teacher. It offers nuanced insight and the experienced growth of capabilities rather than broad brushstrokes on what to avoid. Failure might teach us to hire a good tech team. Success can teach us how to hire a good tech team. Failure might teach us to avoid bad community relations. Success can teach us helpful forms of good community relations which we should seek out.

Many of the failures on the MobileActive list are failures of early-stage organisations. If we imagine each chapter in the lifecycle of a project as a gate on the path to our goals, then each failure prevents us from learning the lessons beyond that gate. I have seen many entrepreneurs who are really great a making pitches, writing business plans, and winning seed funding, but who can’t seem to get beyond the barrier of actually taking their business to maturity. Their repeated experience of failure makes them very good at the early stages but offers limited help once they reach the limits of their experience.

Knowledge, Capabilities, Advice, Mentorship, Apprenticeship

This debate is especially important when we give advice to young people. Those who value failure encourage young people to start their own company or charity. Those who value success encourage apprenticeship first and serial entrepreneurship later.

The argument for failure is based on an overly high respect for knowledge. In this view, perhaps new entrepreneurs will encounter records of informative failures and avoid the mistakes of the past. This view doesn’t account for how people really learn, especially when they’re gripped by the fire of a great idea they want to share with the world. In a mentoring relationship, few things are more tiresome than a mentor who simply dumps advice on the mentee. Learning, even when you have a personal mentor, is a much more complex dance. The nuances of recruiting, developing a customer base, or carrying out a design process are not easily turned into an 8-minute talk. They rely on capabilities rather than mere knowledge.

Even were reports and talks are an effective way to learn, honest failure reports are hard to write. They’re even harder to share outside one’s own organisation. It’s much easier to blame the marketing, models, or strategies than to blame a first mate who was a touch heavy on the grog. At other times, we blame others to preserve our ego, ignoring more basic flaws in our approach or organisation.

Concluding thoughts

To be fair, success can also blind, and lucky success is the hardest to replicate. I’m also painting a bit of a false dilemma for the sake of argument. In reality, we all learn from a complex mix of success and failure alike. Our colleague at the Center for Civic Media and the Berkman Center Benjamin Mako Hill argues that it’s impossible to learn from just success or just failure. In his analysis of the reasons for Wikipedia’s success, Mako argues that good analysis contrasts successes with failures. Studies of effective military training suggest that reflection on both success and failure is a winning combination. Matt and I agree that taking time to reflect is the key practice to cultivate whatever your situation.

Matt Stempeck is absolutely right to highlight risk as the central question in this debate. By publicising failure, Matt wants to encourage innovative risk and discourage ignorant risk. I want to do the same by grafting talented people onto successful projects. Matt’s approach is very much centered on ideas, projects, and the organisations that fund them. My emphasis is more on people and teams. Matt would support failfaires, reflection, and documentation. I would support apprenticeships, mentorship, and perhaps experienced consultants. Both of us want to locate risk onto capable people with innovative models rather than permit risk to be located in past mistakes or a team’s inabilities.

A final twist: Perhaps incubators have the potential to combine both approaches. Communities with experienced, long-term participants can preserve memory about failures and success while offering learning through teamwork. Do incubators exist in the non-profit and civic spaces?