I’m here at Microsoft Research in Seattle for the summer. Today, we had a visit from Nick Sousanis, who was opening an exhibition of his work. Nick is writing his dissertation (on visual and verbal discourse) entirely in graphic novel form. His project has recently been featured in the Chronicle of Higher Education (http://chronicle.com/article/article-content/131393/).

Before coming to NYC, he was immersed in Detroit’s thriving arts community, where he co-founded the arts and cultural web-mag http://www.thedetroiter.com; served as the founding director of the University of Michigan’s Work:Detroit exhibition space, and became the biographer of legendary Detroit artist Charles McGee.

Nick’s background with comics

“My first word was batman,” says Nick, who teaches comics in classrooms. Reading comics is a great way to learn reading, he tells us. In college, however, it seems like you’re supposed to do serious things, “I always did comics on the side.”

After Nick moved to Detroit, he did a comic about voting, “Show of Hands.”

Submitting comics as assignments at Columbia

While at Columbia, in a class for Maxine Green, Nick started to submit comics as academic work. Over time, he stated to submit more and more comics as assignments. Nick became so good at making the case for professors to let him submit comics that he decided on addressing this topic in his PhD.

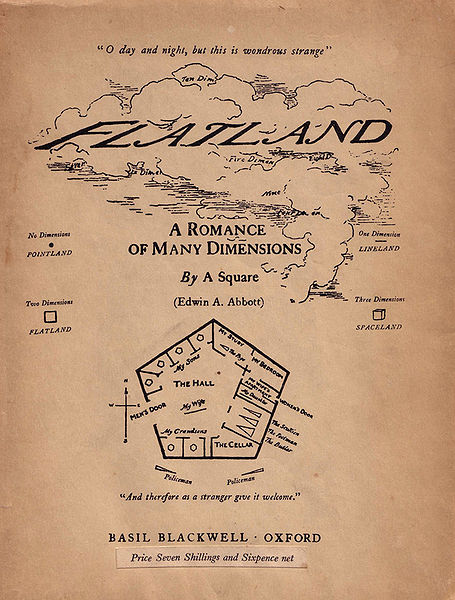

What is flatness?

“Flatness” to Sousanis, is a flatness of sight, what Marcuse calls “a pattern of one-dimensional thought and behaviour.” Like the people in Flatland, we often forget to step out of the world that we know. Learning becomes a recipe — something that’s done to us rather than something that expands what we’re capable of.

Learning tends to be organized into boxes: classes, blocks of time, concepts. We often internalize those boxes and try to fit ourselves into the boxes we’re given.

Picture books are on the decline, says Nick. Why is that? Standardized tests require kids to do more verbal work and less visual work, and parents want their children to perform well on tests.

Links:

– Abbott: http://www.geom.uiuc.edu/~banchoff/Flatland/

– Marcuse: http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/marcuse/works/one-dimensional-…

– Decline of Picture books: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/08/us/08picture.html?pagewanted=all

CHALLENGE TEXT

We need to “challenge text,” says Nick, who included only a single page of text in his dissertation. For most of Western history, proponents of text have been the ones to challenge visual explanation.

Plato argued that thought was better than images. If you can’t trust what you see when you’re making an image, you’re working with shadows of shadows. You look at a stick in a glass of water and you see a bend that isn’t there. Obviously, concluded Plato, we cannot trust our sight.

Descartes doubles down on this. In an experiment with wax candles, he argues that sight and sense experience are untrustworthy sources of evidence– in some conditions the wax looks droopy. In others, it appears solid. Since it’s still wax, Descartes says, our senses are unreliable.

Nick disagrees. Language is a tool and a trap, and we need the visual to make full sense of our world.

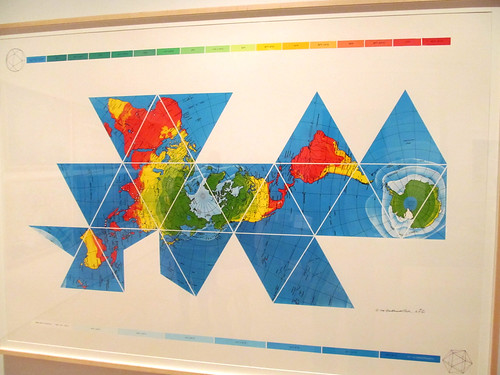

Maps and Projections, Text and Image

Any language we think through, from a map to a thermometer, shows us only part of the story.

Text unfolds linearly, in a sequence. Image in contrast is highly interconnected. Nick shows us a sentence diagram and contrasts it with a Rhizome structure. We get in trouble when we rely only on one way of looking.

Comics

Comics are amphibious — ways to breathe in both the visual and verbal mediums. Perhaps this offers an opportunity to escape the trap of verbal language, to see an issue from multiple views. The term “comics” is an unfortunate term, since we’ve been making pictures to understand our world for a very long time. Comics get relegated to children’s entertainment, and

What is Unflattening?

Nick tells us about Erastosthenes’s discovery of the circumference of the earth. Using simple geometry of shadows, the ancient philosopher was able to calculate the circumference of the earth. His key insight was the importance of using more than one measurement and calculating on the basis of those multiple viewpoints.

Like Erastosthenes’s experiment, unflattening involves adding layers of experience and sense to our picture of the world. Comics allow Nick to walk the talk of visual thinking.

Links:

– How Erastosthenes measured the circumference of the earth: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eratosthenes#Eratosthenes.27_measurement_of…

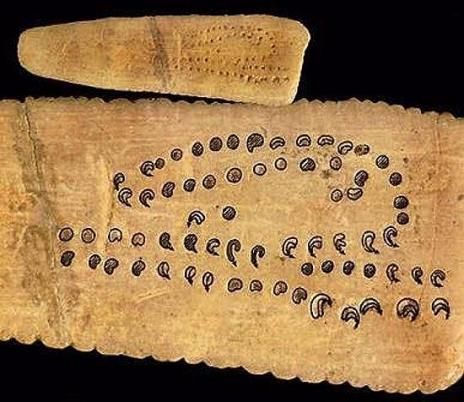

What are Comics?

For Scott McCloud, comics are “Juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence.” It’s a very formal description of ways that we link static images together in our heads.

Nick thinks about comics more in terms of recording time within space. Showing us a lunar calendar, he makes the argument that we have been doing this for a very long time.

Comics are also more than just sequence — we’re able to take in multiple images at once. Drawing from the work of Ian McGillchrist’s work “The Master and the Emisarry” he argues that one part of the brain is better at focus and another side of the brain is more capable at broader awareness.

Links:

– Ian McGillChrist: http://www.iainmcgilchrist.com/

– Scott McCloud: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scott_McCloud

Comics: Detail and Overview

Comics combine these two ways of seeing: the sequential and the simultaneous, the overview and the detail. To illustrate this, Nick shows us a panel from Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” that includes a timeline — annotating the conversation. The example here from “Gasoline Alley” also affords this kind of dual focus.

Text and Image, Entwined

Comics bring together words with pictures in a way that is more closely linked than they tend to be in their boxes on a magazine page. Furthermore, comics can express “multimodally,” using fonts and sketching styles to communicate nuance.

Links:

– Review of “Asterios Polyp” http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/26/books/review/Wolk-t.html

Digression in Comics

Comics create space for digression and process. Nick shows us some of Chris Ware’s work to illustrate how a comic can illustrate process and digression while also telling a story:

Links:

– Kottke’s long interview with Chris Ware: http://kottke.org/11/03/long-chris-ware-interview

Questions

I ask Nick about the possibility of dialectic in comics. Words are great because we have strategies like summarisation and argumentation that allow us to talk to each other and collaborate to improve an idea or make a decision. Does Nick know of any examples of ways that people have a conversation between people via comics?

Nick answers that he hasn’t found any examples of this, and that we should try it. I agree 🙂

An audience member asks, “what’s your process?” Nick responds that his works are philosophical excursions. He might start with the idea that a panel needs to communicate something about nonlinear thinking. He might create some scaffolding sketches to lay out the overall structure of the the panel, fill in detail, and then move back and forth to adjust detail and overview as it proceeds.

Who are you reading, asks an audience member. Nick responds

– Chris Ware is worth reading. It’s hard because they’re sad things, but it’s worth reading. Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth is his most recent

– Alan Moore

– Stitches by David Small (memoir of growing up in Detroit)

There is an upswell of comics that deal with trauma in people’s life, often because words sometimes can’t address what people are experiencing. One example of this would be the Narrative Medicine group at Columbia University: http://ce.columbia.edu/narrative-medicine