What influences do social movements like Black Lives Matter, MeToo or Occupy have on society as a whole?

One hope movement leaders express is that a successful movement can change how we think and talk about key social issues. Champions of Occupy argue that one of the movement’s achievements was getting Americans to talk about economic issues in terms of inequality and the power of the 1%. But it’s difficult to quantify claims like this: how do we know when language, news coverage and public dialog about an issue shifts?

There’s excellent work already done in this field with regards to the Black Lives Matter movement (BLM). Deen Freelon and colleagues have examined the relationship between BLM’s use of twitter and media coverage of police brutality. To further investigate these approaches, my colleagues and I have just published a paper — Whose Death Matters? A Quantitative Analysis of Media Attention to Deaths of Black Americans in Police Confrontations, 2013–2016 — in the International Journal of Communications. Our paper examines coverage of individual police-involved deaths and the following media coverage. We used the Media Cloud toolkit to examine US media coverage of 343 deaths between 2013 and 2016: deaths of unarmed Black men and women at the hands of the police. By analyzing the attention US media outlets paid to these deaths, we were able to describe a “media wave” of attention to the phenomenon of police violence affecting Black Americans. Critical to this wave of attention was the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and the police and community’s reaction to his death.

The period of time we studied includes the deaths of Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice and others who’ve sadly become household names. Implicit in our study is the question, “Why did these deaths gain attention when so many other deaths of black people are ignored?” Data compiled by Fatal Encounters, which tracks police-involved deaths, saw a slight decrease in these deaths during the years we studied, and Frank Edwards used data from the National Vital Statistics System to demonstrate that black men and boys are almost three times as likely as white men and boys to die in an encounter with police. The danger and injustice of death from a police encounter isn’t new, though the attention paid to these deaths after Michael Brown’s death was.

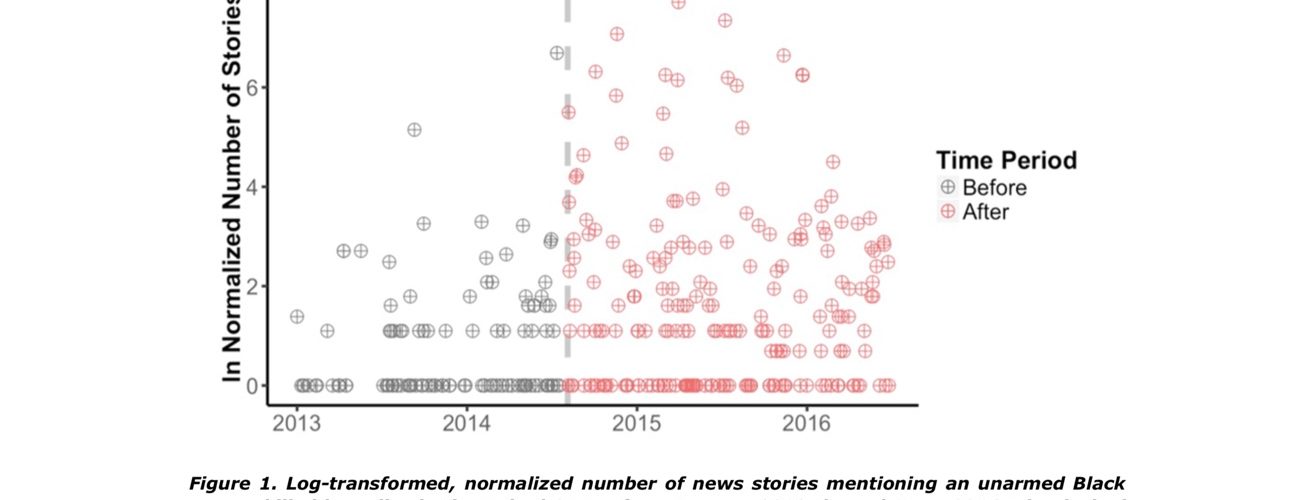

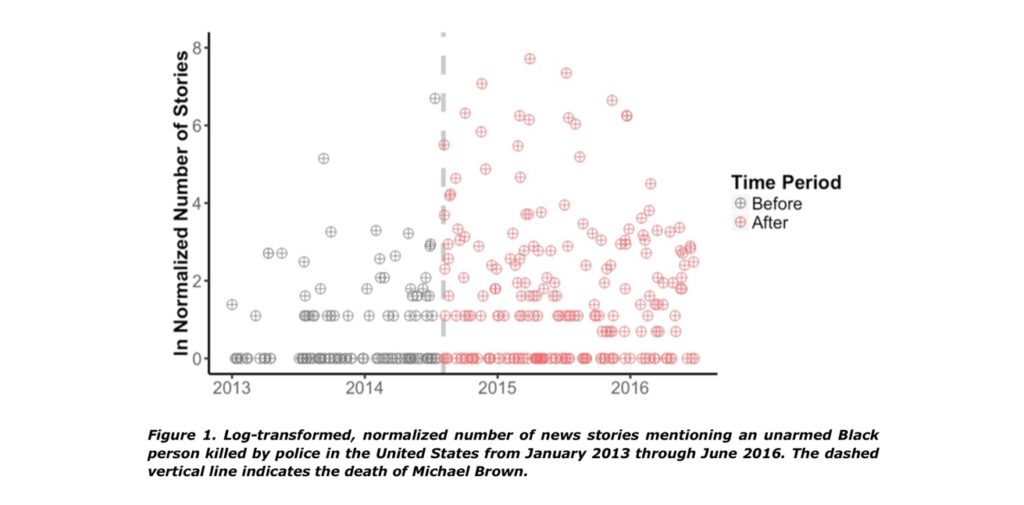

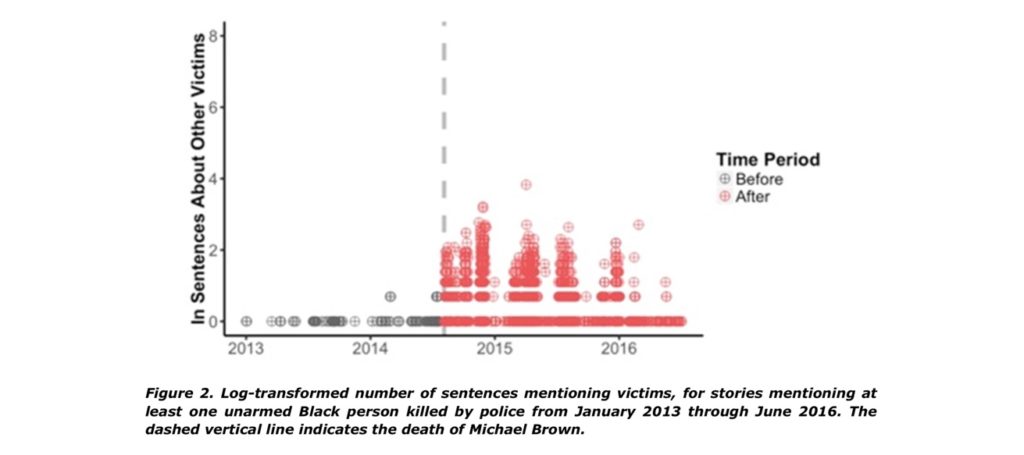

Before Michael Brown’s death in August 2014, a 33-year-old Black man killed by police in a city with the median population had, on average, a 39.34% chance of having at least one article published about him. In our data, after Brown’s death, a similar person had a 64.25% chance of his death being covered by the media. Not only were deaths more likely to be covered at all, they were more likely to be covered in detail, as the chart above — which measures total sentences in the media about a specific death — demonstrates. Because Media Cloud lets us analyze the content of a story, we were also able to demonstrate that before Michael Brown’s death, only 2% of stories about a victim of police violence included mention of another victim. After Brown’s death, 21% of stories mention another victim, suggesting that stories were no longer treating the death of unarmed Black people in police encounters as tragic, isolated instances but as part of an ongoing pattern.

Unfortunately, our data shows that this news wave crested roughly a year after Brown’s death, and that by the end of our study, media (in)attention to Black deaths was at the same level in late 2016 as it was in early 2013. We examined the sharing of these articles on Facebook and found a less pronounced drop-off in attention — we see the wave crest and ebb, but levels in 2016 have not dropped to the 2013 levels, which suggests that there is still a social media audience willing to amplify these stories, even when the stories are less numerous. However, we found that the framing effects we found persisted: stories at the end of our study period were much more likely to mention multiple victims than at the beginning of the period, suggesting that these deaths continue to be understood as part of a pattern.

Our paper does not demonstrate that Black Lives Matter was primarily responsible for this shift in media coverage. In examining media coverage of the BLM movement, we found that BLM received the most media attention in the context of Micah Xavier Johnson, a Black man who killed five Dallas police officers. Johnson was incorrectly linked to Black Lives Matter — he was briefly a member of the New Black Panther Party’s Houston chapter, but the organization threw him out because of his extreme views. Still, Johnson’s concerns for police violence against Black people led many media organizations to frame the Dallas police officer’s death as a possible consequence of the BLM movement.

However, because the movement helped lift up a narrative that connected individual events into a broader story of racism and its dangerous effects, it’s reasonable to connect this news wave with the movement’s efforts. At the same time, the wave of news likely helped Black Lives Matter gain attention and prominence — the relationship between the news wave and the movement was likely reciprocal. One implication of our research is that these news waves represent an opportunity for social movement leaders to introduce new narratives into media coverage. When journalists compete to cover the same story, there’s a competition to cover the same facts in a new and interesting way. Understanding Walter Scott’s murder by officer Michael Slager not just as a horrific instance of police brutality but as part of a larger, nationwide narrative of a crisis in policing gave journalists a chance to distinguish their stories and movement leaders a chance to reframe the story.

My hope is that our research offers both an opportunity to understand how media attention can move in waves, and how social movements might harness and benefit from those waves. My suspicion is that we are seeing similar dynamics around MeToo, where stories about sexual harassment are being understood as part of a broader social trend to condemn unacceptable behavior… but where attention to sexual harassment is also encouraging more women (and men) to tell their stories. Media attention feeds movements, and movements drive media attention. It’s hard to replicate this specific study with MeToo — thanks to efforts from The Guardian, The Washington Post, Mapping Police Violence, and others, we have a fairly comprehensive database of people killed by police, and no similar database of sexual harassment exists. But the methods we outline here, of examining media coverage before, during and after a social movement, should be applicable elsewhere.

This research would not have been possible without the incredible efforts of my colleagues. Rahul Bhargava helped us refactor Media Cloud to make it possible to count and compare coverage of hundreds of different people, a usage we never considered when the tool was initially built. Allan Koworked tireless on the challenging task of crafting searches for each of the victims and cleaning our data. Nathan Matias did the statistical analysis to give us confidence in our findings, and Fernando Bermejo offered the communication scholarship that helped us contextualize our findings within broader thinking about news agendas. I’m immensely grateful to be able to work with such thoughtful, passionate and compassionate people.

Originally published at … My heart’s in Accra.