Today’s guest is Jon Rubin, who teaches contextual practice for socially and contextually engaged art at Carnegie Mellon. This is a live blog by Rahul Bhargava, Catherine D’Ignazio, and others – don’t be surprised by typos or inconsistent tone!

Conflict Kitchen came out of what they don’t have in Pittsburgh. They’ve never sent out a press release, but coverage has never stopped (AP, A Jazeera). Jon shows us an al Jazeera clip about Conflict Kitchen to introduce the project:

Conflict Kitchen – Aljazeera from STUDIO for Creative Inquiry on Vimeo.

Where this All Came From

Jon teaches “contextual practice” – socially and publicly engaged art in Pittsburgh. He started renting storefronts and holding classes there, so the worked produced was shown immediately. In Pittsburgh, this is cheap! Leveraging his institutional settings at Carnegie Mellon, he rented out a vacant space and started doing projects. Conflict Kitchen is his third project there.

The Waffle Shop

The storefront is next to a really busy nightclub which brought all segments of Pittsburgh together. They opened a restaurant because the club owner said “I’ve got a waffle iron. I think you should sell waffles late at night.” The first semester it was a reality show with lights. The next semester they actually built a talk show set. For anyone who walks in. They are open late-night and for brunch which gets a lot of people coming in from church. Sometimes people are confused that there is a talk show going on in the waffle shop. The project lasted four years and over 10,000 people were served.

“Food creates a sense of comfort and conviviality”. The restaurant as a form brings in people that a art gallery, political rally or other form would not. He shows slides from the talk show – “Old Man Louie” who wears an old man mask even though he’s already an old man. A woman who came in on her birthday for waffles. Jon learned from this, how to use irrational strategies to draw people in. Food is his seduction for people to engage.

Conflict Kitchen

The project developed with Dawn Waleski who lives in California now. They were challenged by the hip hop restaurant who was having food sold outside his club. He said, “Come on, don’t be a fake business. Compete!” So they decided to try to do that. How could they be a center for political discussion? How could they create a space for ethnic groups that have small populations in our city?

They stuck a facade onto the building (cleverly getting around permitting issues). Now they run two restaurants out of one kitchen. Now that this project has moved out over the internet, various people are asking them for advice. They stumbled onto this idea; nobody liked the idea. They said there was no market for the food, nor the political conversation. Jon talks about these as bad business model, but it worked.

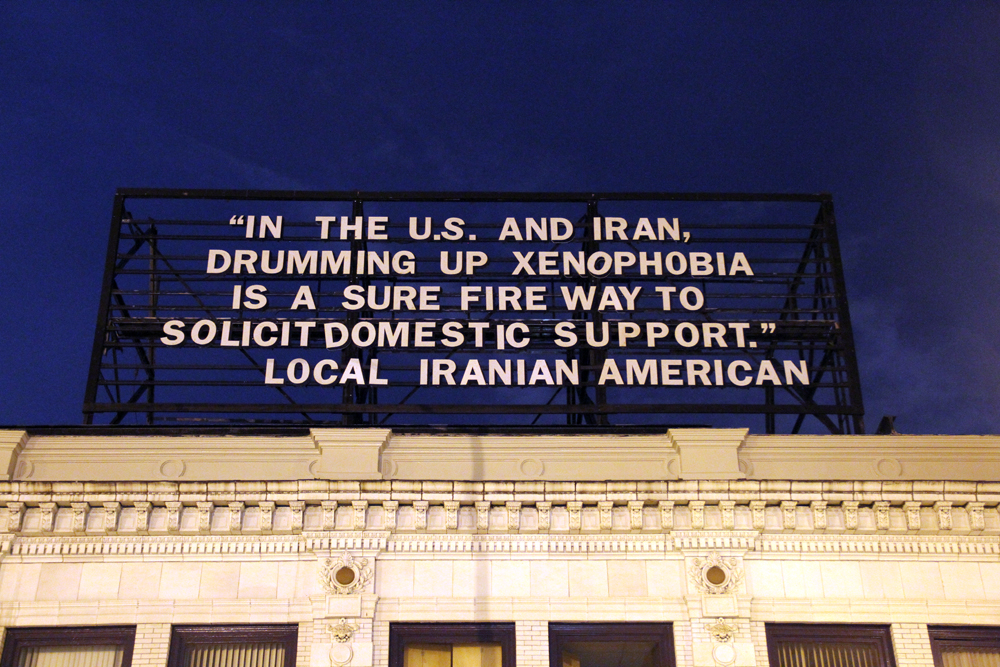

The first version was an Iranian one. The visuals are important. They wanted it to be strange and wonderful to the visual landscape of the city. They worked with local Iranians as well as Iranians from other places. This came from the rhetoric in the media at the time (four years ago), that was over-simplified. Could we create a place that complicates people’s perspectives? And bypass people’s ideology with hunger?

“Can we bypass ideology with hunger? Can we engage people on a daily basis?” Jon stays they are not a pop-up, they are a restaurant. “The pop-up thing implies a lack of depth and commitment, and that we know what we are doing and we will tell you. ” They tried to create a space for co-education and co-learning. You have to have a call and response system, an iterative system. They decided to use the food as a storytelling device. Jon says, “Let’s let the food be a mechanism for carrying information.” The wrapper carries text that tried to connect the culture to Pittsburgh and its residents.

Jon is interested in the space that opens up when you are waiting in line for food. This is like the space in the talk show, but more focused in terms of conversation. He wanted to create a space for curiosity, and then fill that space by the staff, who are expert conversationalists.

How do you get people to come with a question? “If there’s too much curiosity then it’s befuddlement. But too little and there’s nothing to talk about”. The staff are really important here.

After 5 or 6 months they switch cultures. After Afghanistan came Venezuelan. They’ve gone to Cuba to conduct interviews and learn how to cook different foods.

A year ago they moved to the most central part of the city, across from the Carnegie main library. The crowds have grown, and it has changed the way they engage with the public. They are open every day from 11 – 6. They have discovered that they are a great publishing venue – people really read the food wrappers. The latest version is selling a North Korean cookbook. Non-fiction is a completely constructed and playful genre.

Experiments That Move Outside the Restaurant

They include projects and events. They have set up large tables and done collaborative dinner parties with places like Tehran. They are cooking the same recipes on either side. Amusingly the Conflict Kitchen food was from scratch, and the Iranian was from the store. They’ve done cultural festivals, hosted school groups. They integrate the billboard on top of the building. When they needed a new space they functioned out of someone’s home.

They’ve also started a virtual presence experience. They offer folks that come in the chance to eat with someone that is “foreign” – from the land the cuisine is from. A staffer will wear headphones, and be connected to someone on the other side that lives in the place the cuisine is from. The local person is a “human avatar”. Jon says, “Elise is an empty vessel, but also a hyper-local human body.”

What they are trying to do with this experiment is to create a simultaneity of place. How do you get people to pay attention? What makes things uncanny? “It’s to make the familiar unfamiliar to be in the present moment again.” It complicates identity. The “vessel” is a woman, the Iranian on the other end is a man. They’ve done this intervention with local-avatars in various cities around the US. Museums, libraries, and more.

He discusses a project for a biennial in Porto Alegre, Brazil. The prompt is that they tell people that they can take a free swan boat ride with Chavez or Obama. They hired actors that play the roles of these heads of state. In Brazil, you could see evidence of both the IMF and Chavez/Venezuelan policy. They thought this would be a great device to elicit stories from the Brazilian public. Obama would say, like a lover, “What do you think of me?” The public would say everything they really thought. The same with Chavez. Both of the presidents would approach people waiting for something and hit on them, basically, to go on a boat ride with them.

“How do you seduce people” is a core question for these interventions. On these rides they record what folks are saying. Then they transcribe them and the actors give speeches from podiums every afternoon just repeating what the people said to them. The presidential actor presents these as his views. You get “a politician who says what you want him to say”. The president ends up sounding very self-critical. This is turned into documentary and storytelling.

They’ve brought this idea back to the Conflict Kitchen. “The Iranian speech” is a crowdsourced speech. They have an Obama impersonator give this speech locally at the restaurant. Both Cuban and Iranian versions of this speech are crowd-sourced from residents in those countries. They also disseminate these speeches online.

The Cuban Speech from Jon Rubin on Vimeo.

Jon shares a video of the Obama impersonator giving this speech. The resemblance is uncanny. The Obama impersonator says things like “I don’t remember the last time I even talked about Cuba.” and “We say we like human rights but then we do business with China”. The speech is schizophrenic. We want to get a debate out there. We don’t want to simplify anything. We are into encouraging curiosity.

Bridging Space

Another example is a big sign Jon placed in Columbus, OH which showed live time and temperature from Tehran. They’ve tried to create weekly lunches that cover these topics, so they can respond more quickly.

Now the restaurant is focused on North Korea. It’s very hard to do research on North Korea. What they did was work on a project with North Korean defectors outside of Seoul. You can go into North Korea but it’s a very controlled experience. He shows a dinner where they had 250 eating and depending on which side of the table you sat you were from “North Korea” and the other side of the table was from “South Korea”. North Koreans only eat meat 2-3 times a year so this version of the restaurant is a vegetarian one.

They have also started having group skypes where the North Korean chef is doing a cooking lesson for networked people. So we have people in Buenos Aires who are sent a shopping list beforehand and then everyone cooks together over skype. So there’s an interesting aspect of just what is the equivalent of the ingredients from place to place.

He shows a video clip of making korean pancakes. Then everyone sits down and eats together over Skype. He says that the conversation was more organic and actually worked better than regular Skype. A question about soy sauce might lead to a political discussion.

Final Thoughts

Jon shows a slide about how the project has traveled. The project itself has become a tourist destination. People are always coming by from other countries. News outlets are interested in it. There is more international attention than national attention. People ask them if they franchise this on a daily basis.

Jon always feels like they are never really actualized. They could figure out how their city could become better citizens. The Pittsburgh residents are their first audience. People in Pittsburgh know about it. They are open 7 days a week. They are like any other business. They have revenue. They think about economics as much as anyone else. They are trying to struggle and survive just like the others. That gives us some credibility with our customers – that we are not just some fancy art project.

Questions

Mine asks: Have you ever encountered negative reaction from any customers?

Jon defers to Griff who worked the window a lot

Griff – Sometimes people would say “I don’t want your propaganda”. Never anything serious.

Jon – More online than offline. But surprisingly the haters don’t show up to the window. If you serve good Cuban food then that really trumps everything. You might be like “Castro’s an asshole but God this is good.” We had a very smart, hardline guy come to the restaurant. This guy came and spoke and was counterpointing everything that the audience believed. The next person was someone who had a photo of herself kissing Fidel.

Ethan: Was Fox News’ coverage positive?

Jon: It was Fox Latin America. The journalist who covered it was quite serious. But when he was on the news show he was on with one of those silicone newscasters. She plays the dumb American and kept tripping him up. He was outside his comfort zone and started making stuff up. It was a weird thing and confusing.

Hiromi – I love the playfulness and humor. You mentioned social media. Right now the most popular YouTube channels are comedy channels. I wonder what you feel about humor.

Jon – Obviously I’m very interested in humor as an aesthetic in art. on eof the challenges that visual artists have is that art is not like music where it just hits you in the gut. Humor is the thing the visual arts have that gets you in the gut. I use humor that way to bypass the intellect that way. Ironically that you bring that up – I’m doing a project with my friend who lives in Iran to have a sitcom in Los Angeles and Tehran. The family will be stuck in two realities at the same time. The kid knows what’s happening and the others don’t. Conflict and miscommunication is the core of comedy. I’m interested in that being an online show. In Iran, 70% of the population is under 30. A lot of the media they see is on the Internet and it’s from the US. Can we create an innocuous environment to bring up political issues without censorship?

Erhardt – There were two series of reality shows about Iranians – Shahs of Sunset.

Desi – You mentioned that you get weekly requests for franchises. HOw do you maintain the integrity of what you want to do? Is there an open source model of Conflict Kitchen that others could use?

Jon – It is open source to a certain extent – when people ask them if they can do it where they live, Conflict Kitchen says “go ahead”! They’ve had families and school groups that do it in various areas. They are also developing a cookbook. They’ve thought about the franchise model, but the challenge is economic. Jon thinks it makes sense for what they’re doing, but they aren’t in a place where they can make that happen. Locally, they are thinking about collaborating with a local whiskey to think about culture and booze and so on.

Adrienne – I’m curious what happened to old store (the Waffle Shop), and are you still affiliated with the school (CMU)?

Jon – The waffle shop closed after four years. All that is left is the billboard. The Conflict Kitchen is a research project, under the Studio for Creative Inquiry (run by Golan Levin). The staff are employees of CMU, through the business office. The food business is self-sustaining at this point, and supports some of the side projects. The research center has non-profit status, so they are thinking about grants as a funding option.

Sasha: Have you talked with Pittsburgh as a city – to bring together people around city development issues?

Jon: Yes, we try to be responsive to our customers. But we’ve decided not to take on internal, local conflict. The people that have the most problem with our cuisine are the vegans. They say that we are contributing to the conflict around the world.

This is just US covert and overt engagement around the world, and there is plenty of that.

To be macho in North Korea is not to have spice. it’s a regional thing and comes unspiced. But we are selling food that’s primarily unspiced. We have a large south korean community in Pittsburgh who are into it. I try not to make culinary decisions purely based on my tastes.

Culinary relations between countries are fascinating. Afghanistan, for example, is between many different cuisines. Customers can reference back

Catherine: I find it powerful that you decided to be in the specific place. The Pittsburgh eaters are the core audience. There is a power to not being the symbolic pop-up. It isn’t temporary like a lot of art projects.

Jon: The “Speech of Swans” project was temporary, but fun. The idea that he can bring it back and add it into the mix of things that they do, that’s what he likes. Running the Conflict Kitchen feeds him on a deeper level. He lives just a mile away. These projects are a part of his life, and the civic life. This isn’t like have a show in a gallery for a month. What he’s doing is totally normal for a person living in the city. For an artist perhaps this is radical, but for the rest of humanity it’s just normal.

Jill: I’m interested in the diversity of the audience. Are there economic issues around how much you charge? Does that preclude people from participating?

Jon: We are cheap – you can get lunch for $6. College students can afford it. The most you’ll spend is $10. We don’t give food away for free. It prevents us from being fancy with the food and too experimental. Occasionally Robert our chef will do some events to let his freak flag fly. We are going more weekly specials where we are hybridizing the cultures. In the end the goal is that anyone can eat it. We have great regulars. People who come four days a week.

VizThink

Willow’s vizthink of Jon’s talk is here: