Can we graft our humanity and our souls onto the web—using the Internet to craft a life story which grows in richness over time? In the 19th century, the Romantic poet Wordsworth famously stated: “all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings; it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity.” Jonathan Harris, who spoke at the MIT Media Lab last Monday, is trying offer something similar with his new storytelling platform Cowbird.

The creation of Cowbird is deeply rooted in Jonathan’s personal quest of self-discovery through artistic creation. Following a number of early successes including We Feel Fine, Universe, 10×10, I Want You To Want Me at the MoMA, and The Whale Hunt, Jonathan felt less and less in touch with his core personality. As Jonathan tells it, Cowbird came out of his attempt to reconnect with himself and the world.

“One without a myth is like one uprooted, having no true link either with the past, or with the ancestral life which continues within him, or yet with contemporary human society. To know your myth is the task of all tasks.”

— Carl Jung, from quoted by Jonathan Harris

(from “Symbols of Transformation of the Libido“, vol 5 in the collected works, p29)

Soon after his 30th birthday, when a car crashed into a house on his street, Jonathan decided to leave New York. He drove to his childhood home in Vermont and cleaned out 18 rubbish bags of old possessions, intending to drive West and live like a hermit. Looking through old photographs, he felt as if the Internet didn’t offer the same kind of longevity. So he left regular Internet behind as well.

Jonathan traveled from one art residency to another: the Badlands of North Dakota, the Santa Fe Art Institute, Flokadalur Iceland, the Burlington Contemporary Arts Center, the Stockholm Public Library. On this journey of personal myth creation, Jonathan refined a confessional literary style which combines digital photography with intimate reflection and stream of consciousness interviews:

In ten years I know that most of the doors will be closed, and that the act of closing them softly will be a lot like gassing a faithful labrador you used to love but just can’t care for anymore, and this passive silent softness will somehow feel more violent than gorging out organs with a spoon.

Come into my home and I will serve you coffee cake and milk and shark meat. I will pull it from the ceiling and you will brush away the flies and I will cut it sideways with my pen knife and you will run into the grass because you cannot stand the smell of it and I will laugh and pound the table with my hand and spill the coffee.

Jonathan compares this slow-paced style to the media he used before going digital: oil paintings and journals containing watercolours, collage, and even physical objects like beads. Although Jonathan shifted to the Internet when his notebooks were stolen at knife point in Costa Rica in 2003, the Internet never offered the richness and longevity of that lost notebook.

Cowbird

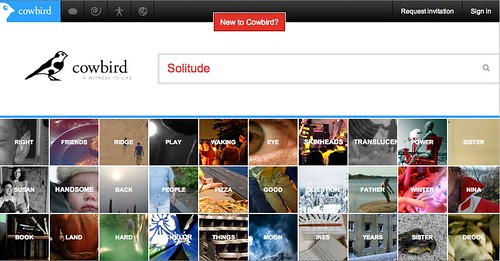

To make a place on the Internet for deep personal reflection, Jonathan has created the storytelling platform Cowbird. He describes it as a “space for reflection,” an “archive of universal moments of human intimacy,” a “shared narrative saga on collective events,” and “a medium for participatory citizen journalism.” This is a lot to ask of a single website.

Cowbird does offer a refreshing contrast to an Internet dominated by advertising, real-time mobile status updates, social metrics, cynicism, and the lulz. Everything about the site is designed to encourage reflection. Jonathan explained that he wanted to create a “contemplative, church-like environment” with “core spiritual concepts” :

- Storytelling takes time and reflection

- Teachable moments are the main moments in our lives, which we need to find and share with others to learn from

- Our story fits together with the stories of other people through Sagas

These spiritual values have inspired Jonathan to design a very specific kind of artistic form and creative experience. Every Cowbird story has a single photograph, a creative text, an optional voiceover, and a single-term universal theme (such as “road” or “waking”). Multiple stories form an individual’s collection of stories. They can also be part of a larger “Saga” such as the Saga for the Occupy Movement.

Jonathan directed us to two stories which he especially likes. The first is Scott Thrift’s sentimental, melodramatic meditation on a photograph of his ex Angelique. The second example is equally sentimental, a beautiful photograph Jonathan took of a couple kissing just as the police moved in to break up the General Strike organised by Occupy Oakland last November.

Cowbird’s design is a kind of sentimental universal minimalism. Text is avoided where possible in favour of sketched icons of silhouettes with hover explanations (not accessible on mobiles). Story image thumbnails have minimal labels such as “Road” or “Land” or “Father.” Fullscreen views reminiscent of the WriteRoom aesthetic are used to create new stories. Readers must scroll for details: first the photo, then the story, then the medatada and further links. Panning animations on images everywhere make full screens and grids possible; they also evoke sentimental notes in the Ken Burns style.

Despite Jonathan’s Icelandic sojourn and frequent reference to the Sagas, Cowbird draws much more from American documentary storytelling traditions. Icelandic sagas such as Egil’s Saga often retell the adventure epics of bloody feuds and great men—the product of social oral traditions and the feasting hall. Cowbird offers something very different: an opportunity for reflection in solitude, connected to the larger stories of humanity, perhaps to the sound of violins or acoustic guitars.

Storytelling confessionals connected by a universal theme are a common style for Chicago Public Radio’s This American Life. Cowbird also reminds me of Derek Powazek‘s mid-1990s storytelling web magazine Fray. Other related projects include StoryCorps, who collect interviews for the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress and broadcast on NPR’s Morning Edition. A more recent analogue might be the Zeega Project‘s Mapping Main street documentary, which retells the story of Main Street America by sharing photos and audio from America’s actual main streets.

Unlike public radio shows, Cowbird isn’t mediated or curated by professionals. Cowbirders (Cowflocks? Cowbirdians? Cowbeeps?) don’t have to wait for the StoryCorps bus to arrive. Nevertheless, a strong connection to existing stylistic formats will probably work in Cowbird’s favour. In a recent talk at the Berkman Center, Benjamin Mako Hill argued that Wikipedia succeeded because people know what to expect from the style of an encyclopedia article. Perhaps the same will be true for Cowbird stories.

Jonathan also describes Cowbird as a reaction against social networks. If the mobile and social web have made us alone together, Jonathan wants Cowbird to help us be together alone — creating and encountering personal reflections away from the busy digital lifestyle. Although Cowbird has the equivalent of likes, friendships, groups, and tags, they’re kept hidden in small icons or at the bottom of the page. With a fundamental reliance on hover actions, Cowbird is difficult to navigate on mobiles and tablets. This might not be a weakness for a site designed to help us escape a busy, communication-driven life.

Jonathan protects the Cowbird aesthetic from early adopters through an invitation-only registration system and an onboarding process. New users are encouraged to view example stories, “love” 20 current stories, and join some sagas before posting their own story.

Concluding thoughts

Cowbird reminds me of the intimacy of personal blogging before the rise of the social media business, concerns about privacy, and the realisation that stories which feel true can deceive. Jonathan’s preferences for sentimental melodrama and psychoanalysis do pull Cowbird away from journalism. Without more support for framing the context of a photo and shaping a specific narrative, reporting will be hard. I also think that themes and sagas may be hard for viewers to stitch together. In my own creative work with linked documentary anecdotes of photographs and voiceover, viewers preferred to let individual stories wash over them rather than develop a larger narrative understanding of how they connect. I think the same will happen on Cowbird.

In the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth suggests a role for personal reflection in the writing and reading of poetry. He urges the reader to judge his poems “independently, by his own feelings” rather than by style of composition or the opinions of literary critics. Despite my concerns, browsing Cowbird makes me feel happy. I think it’s beautiful.