This morning in an interview about yesterday’s Guardian Datablog post on gender in UK news, the Tow Center‘s Anna Codrea-Rado asked me for ideas on how data journalists and academics can collaborate. I mumbled a response about the cycles of peer review, models of public engagement, and expertise at visual presentation.

Inside, I was thinking, “Dear me! She thinks I’m an academic or maybe some kind of expert. Am I an academic? What does that even mean anymore?”

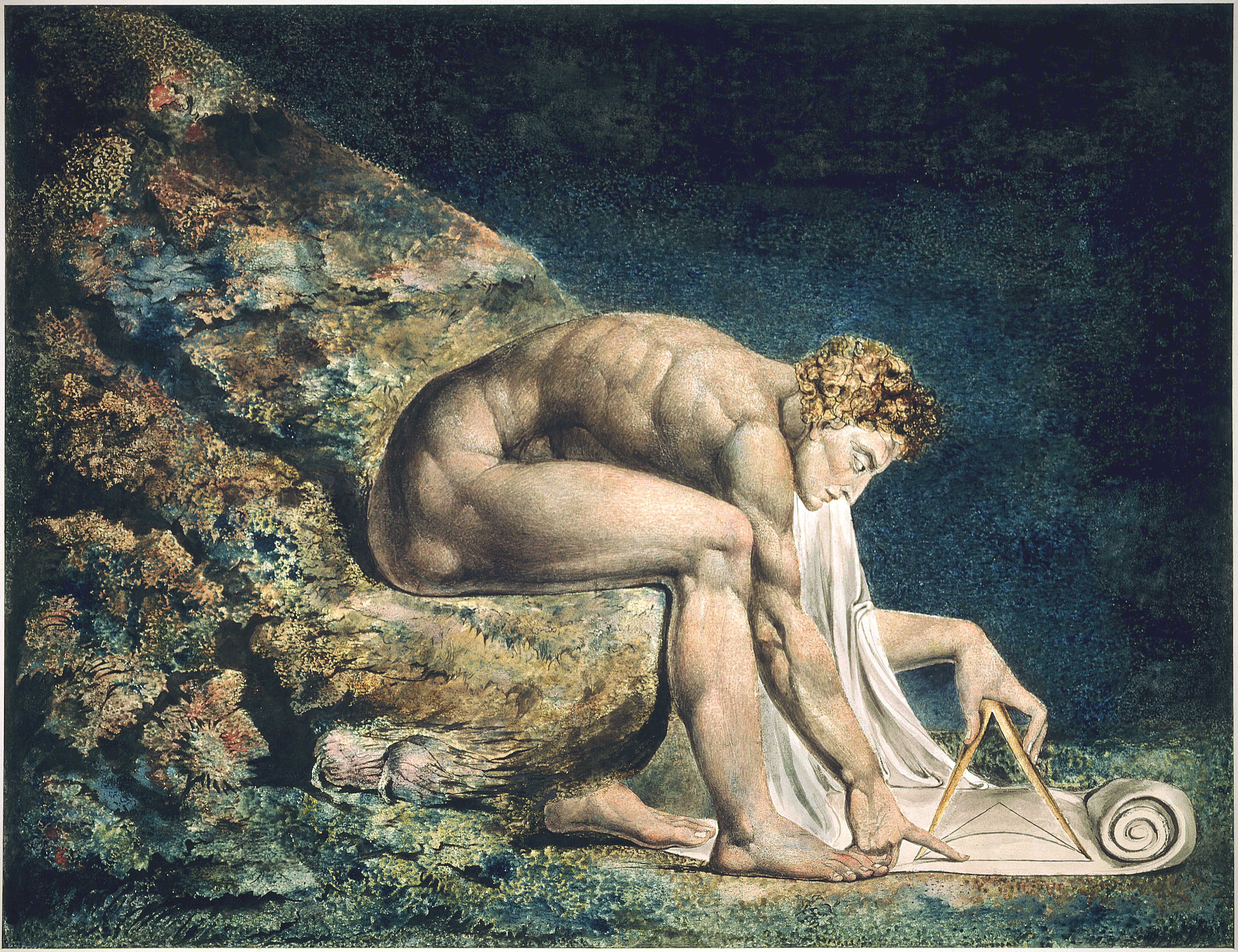

Academics aren’t noiseless patient spiders, experts who meticulously pursue answers. We make a lot of noise and a lot of mistakes. We’re more like journeying enquirers, people with a personal bag of tools who tinker with ideas from within a social context.

Conversation versus Certainty.

I do most of my work online, as part of a conversation with the network of people who care about similar things at any given moment. I often post half-baked ideas to start a conversation that might lead to further ideas. Certainty, in contrast, is more at home with broadcast notions of authority. As an enquirer, I take my ignorance as a given and try to facilitate activity that moves towards understanding.

This half-baked post is exactly the kind of thing I’m talking about. Do you feel the same way, or do you disagree? What’s in your enquirer’s toolbag? Leave a comment or send me a tweet to carry on the conversation.

Biela Coleman, who currently focuses on Anonymous, recently wrote about making the transition from expert to public enquirer:

to be public about your work, while you are doing that work is no easy task; in fact it went against everything I was used to as anthropologist, which was to delve and burrow as deep as I could into a topic/world, and come out the tunnel on the other side, about a year later, ready to start conveying some insight and arguments.

Journalists among you are probably nodding your heads at this point. Two days ago in a talk at the Media Lab, Ta-Nehisi Coates said much the same about his work at The Atlantic. Coates often posts a tidbit of research and explains why it’s important to consider. Readers then add detail and commentary well beyond what Coates could do alone.

A few months ago, I wrote a personal reflection about public, networked enquiry. Here’s how I told the story of my gender project:

In many parts of Cambridge [university], the most valued intellectual creation is the argument. Students are measured by our ability to produce convincing answers to important questions. At the Center for Civic Media, we participate in an ecosystem of open research: real-time collaboration with broad networks over Twitter, blogs, livestream videos, data visualisations, videochat, and email threads. Research is a roughdraft-and-tumble activity, a fragmented, public, networked conversation that converges toward understanding.

Consider, for example, the story of my work on media representation. My interest started with a Guardian Datablog post about women in UK media. When I retweeted it, Knight president Alberto Ibarguen tweeted back to express interest. I emailed the civic email list to ask for ideas on detecting gender bias in the media. Ethan showed me Cameron Marlow’s blog post about Facebook diversity. Together with David LaRochelle at Harvard, I built an afternoon prototype to see how well we could detect gender in blogs and mainstream media. It worked!

We upgraded the project to an independent study, and I spent a semester learning the issues and building software to measure gender over 2 decades of the New York Times. I soon found myself having coffee with Joseph Reagle, who has carried out large-scale research on gender representation in Wikipedia and Britannica. I have enjoyed fascinating design sessions with Irene Ros, maker of beautiful visualisations of journalists’ publishing behaviours. After giving an Ignite talk about the project, I received offers from journalists and newsrooms to collaborate. My work on media representation has also led to conversations and datavisualisations with the Global Voices community.

This idea which started as a retweet is now my MS thesis and will have more than half a dozen collaborators by the time it concludes.

The Guardian Datablog series has convinced me to embrace this enquiring approach. My work with the Guardian has helped me find new collaborators and put me in contact with broad perspectives on gender in the news. Put frankly, my research would be much lower quality if I had tried to develop certainty and expertise before using my voice.

Innovation, Outcomes, and Risk

The desire for certainty limits creativity and innovation. Media Lab director Joi Ito likes to argue that it’s not possible to be innovative if you already know the questions. He often urges us to make space for serendipity and to take uncomfortable risks.

Innovation and risk-taking are especially important in journalism and technology. At the Center for Civic Media, we try to to inspire innovation and develop ideas that have genuine relevance for news and civic life. We can’t do that by just answering the old questions or merely studying what currently exists.

The Enquirer’s Toolbag

The journeying enquirer’s toolbag isn’t a set of skills. It’s a collection of approaches and ethics that will vary by person and subject. Here are some that I value:

- Facilitating Conversations. Whatever the approach, a good enquirer is capable of bringing people and ideas together in fun and meaningful ways: unconferences, dinner parties, jam sessions, brainstorms, mailing lists.

- Listening. It might be interviews, user studies, liveblogs, hours in the library, or sentiment analysis across millions of datapoints. However you do it, you’re missing the point if you don’t pay attention to the ideas and experiences of others. Having a public persona is fun, but being an enquirer isn’t ultimately about you.

- Communicating Ideas. Good communication skills go well beyond good writing. This area includes always having business cards ready, learning good email habits, giving clear talks, and asking good questions. Sketches, storyboards, and demos are also useful forms of communication.

- Learning by Making. Writing a computer program is a great way to develop well-defined understanding of a topic you don’t yet understand. This is about more than code; maybe you’re developing a workflow or social process. Design thinking fits here as well, from paper prototyping and user stories to role-playing and participatory design.

- Play. Although we learn much by imagining and creating something, when we play with the things we have made, we discover unintended possibilities and unexpected outcomes.

- Sharing & Learning. Sharing has importance beyond communication. By formalising and articulating what we learn, we question our experience and package it for our use elsewhere.

- Direction. I choose this instead of words like “focus” or “goal.” Enquirers often don’t know where something will lead. It’s okay to do things because they’re interesting, cool, and fun. However, projects need a trajectory, especially if we want to treat participants with respect. It’s incredibly helpful to know the next step and have a good reason for the one you’re taking now.

- Transparency. By definition, a journeying enquirer will often have incomplete or mistaken views. In addition to acknowledging that reality, we should be open about our process and honest about our limitations.

Does this match your experience? Have I missed something? Leave a comment to share your view.