Today with Matt Stempeck and Stephen Suen, I’m liveblogging ROFLCon, a conference for things and people who are famous on the Internet. The livenote index is here.

Christina Xu, event organiser, starts off ROFLCon to cheers. It’s amazingly packed venue: “One out of eight people in this room have done something crazy on the internet.”

Jonathan Zittrain is a Internet phenomenon. Emerging from humble beginnings as a longtime Compuserve forum sysop, he is now Professor of Law at Harvard Law School where he co-founded the Berkman Center for Internet and Society.

He starts by saying that fame can be tricky: “Just before the talk, someone came up to me and said, ‘‘are you the huh guy? I thought you were the huh guy!’ I’m not that famous. I can aspire. In this room room is the engine that makes the internet sing…in an offkey note. Who’s minding the store? Is this going to be a day without memes?

“Where’s Tron Guy?” asks Zittrain. John Maynard, in full costume, raises his hand, and the room bursts into applause.

Jonathan isn’t sure if he’s one of these “Internet ROFL people” — hence the tie. Even those who aren’t part of this tribe will find it hard to explain what we’re doing this weekend to friends and family. But Jonathan does have some background in the Internet. He shows us a picture of him using a Texas Instruments home computer with a 300 baud motor, with the obligatory model rockets and Webster’s Collegiate Thesaurus– just because you might run out of words.

In his younger years, Jonathan used to work for CompuServe and also got involved in politics. He threw his weight behind Mondale Ferraro 1984. “At least I carried Minnesota, he says. And the district of Columba.” When I wasn’t doing those things, Jonathan says, he was usually spending time stuffed inside a locker. “Whatever that does not stuff you so that you die, makes you stronger.”

Jonathan thinks the image of a nerd stuffed in a locker helps us understand memes– it’s a dramatic moment of pathos. Of those who do the stuffing, he says, “They’re all crazy, I’m normal… they’re bad and we’re good. And here’s to us for being good.”

Is the internet a form of retreat from real life for those who get stuffed in lockers? No. At the base of a lot of memes is some authentic, unguarded voluntary moment. There’s artifice around it, but there is often something authentic beneath it. That’s not *always* the case– consider Dramatic Hamster. Sometimes a Hamster isn’t a hamster. But other memes, such as Socially Awkward Penguin, strike a chord of authenticity.

Wires can be crossed when this culture is commercialized. The nerds struck back against Hot Topic when they produced a t-shirt of RAGE GUY. At this point AJ Mazur of Know Your Meme speaks up, “I had to talk to the CEO of Hot Topic” to explain the meme and the campaign.

[applause]

And of course, you are ALWAYS at risk of not knowing your meme. You could be the godfather of memes and still someone would be waiting to pop you. Jonathan asks what happened, and AJ says that the secretary was more familiar with the 4chan campaign against Hot Topic than the company leaders (context: Race Guy on Know Your Meme was an operation by 4chan to reclaim the meme by poisoning it). And are 4chan doing this ironically or because they’re angry? And the answer is, ‘Yes’. But commercialisation is also complicated: do we get angry at Amazon for selling the t-shirt of the three wolves howling at the moon when the t-shirt itself started the meme?

There’s something about commercialisation which is always at arms length of Internet culture. Jonathan talks to us about the most recent Calgary Comic Con, where they invited the entire cast of Star Trek: The Next Generation. Going to the cons involves waiting in lines to get your photo with the cast. It has an Apple Commercial 1984 feel to it– take a photo with the cast, you cannot touch the cast. Jonathan also tells us about one of the least proud moments of The Oatmeal, a contest for advice features. There appears to be a negative attitude towards those who intentionally try to “engineer” a meme. People don’t like being prompted—it feels like trying too hard, feels inorganic.

We like unstaged authenticity, like Disaster Girl, who grins deviously as a house burns to the ground behind her. She rather enjoys the attention, and we are pleased to see her embrace her inadvertent success, but there are still lines that you can cross. That line is definitely crossed once you;re running your own network and have a store.

Internet Fame is like winning the lottery — it seems good until someone gets killed. What better example of this ambivalence than Star Wars Kid? So far as he knew, this was an exercise that would be completely private. He didn’t realise when he turned the camcorder in at school that it would be posted to YouTube. Jonathan shows us the video of the the Matrix Version of Star Wars Kid. In Wikipedia, there’s a debate on the talk page on whether or not it is right for Wikipedia, the knowledge repository of record for humanity, to include his name in the page. Ultimately, they decided not to name him, despite the fact that the mainstream media has done it several times. And people on Wikipedia fell into line– upholding the process with which they disagreed.

Can we build an infrastructure of meme propagation that respects people’s preferences. He shows us an Awkward Family photo site with an image that says, “Image removed at request of owner.” There are enough yuks to go around, so why not take down private content when someone asks us to?

Jonathan would love to see an infrastructure built native to the web which makes it possible for people to opt out of the celebrity of being a meme. This isn’t DRM, but maybe something like robots.txt (a directive that tells web crawlers like Google which subdirectories not to index). Search companies respect robots.txt. No Internet organisation created this. But people and companies respect it anyway– a way to say, “Do you mind?” This is often used with court documents. How could we build this into our technology and our culture? One guy made a t-shirt that reads, “I do not agree to the publication of this photo.”

In short, how can we enjoy the culture of Lulz which also respecting people’s wishes? Star Wars Kid, by the way, is doing fine. He’s now in law school…where all crushed memesters go to take on the world.

Privilege-denying dude is another instance of the Corbis stock photography model of memedom. Both the photography company and the model objected to his becoming privilege-denying dude, lest he find himself ostracized by society. Another guy actually stepped forward to take one for the team and fill the role. This is a subtle exception to the rule: when you voluntarily offer yourself up to create a meme for the greater good, it is better received than when you try to create a meme in your own self-interest.

Jonathan points us to Oink’s Pink Palace, a filesharing site. The rules read: “If you choose to use one, a cute avatar is a must. It’s far better to not have an avatar that to have one that breaks the rule.”

How can memes move offline into the world of politics? Jonathan shows us a video of Bill O’Reilly justifying his “tide goes in, tide goes out, you can’t explain that” comment in an interview with the president of American Atheists. In the past, people would have said, “huh.” But now we can turn it into a meme. Jonathan scrolls an entire stream of meme, with Bill O’Reilly’s harrowed visage rolling by with countless captions overlaid.

What’s going on here? New avenues of dramatic expression are being opened up by Internet memes. Jonathan shows us a photo of the U.S. Senate, captioned with meme logic: “This is why we can’t have nice things.”

The most obvious junction point at which memes feel licensed to go political is the point at which the Internet is threatened, such as this combination meme using Disaster Girl to talk about Internet censorship.

Memes and politics have become most prominent in Anonymous’s pro-Wikileaks DDoS attack operations. When you hear FOX News saying things like “a group of people in masks are attacking the Internet with a Low Orbit Ion Cannon. They’re charging their lasers!”, it sounds scary. But when we look at it, we understand how goofy it is. Jonathan calls this the spirit of Ghostbusters. The ghosts were real in the movie — and the characters were taking it seriously — their lasers were loaded. But they had a good time taking out the ghosts.

The old guard of hackers doesn’t take this approach. Jonathan shows us a press release by 2600, condemning Denial of Service Attacks. In the meantime, HBGary Federal, a security firm, promised to release the names of Anonymous members– for which they retaliated by defacing the company’s website. Is this serious, funny, ironic? To Jonathan, this is one piece of the phenomenon of memes which has reached out into the world of action. And the real world bites back.

Jonathan directs us to think about Nazi Germany, showing a photo of Hitler’s memetic moment from Downfall. “I realise I am now living Godwin’s Law.” In the Nazi era, would people be making Downfall memes to mock Hitler? Or is that too recursive? Let’s think about authorities, who depend on fear and authority rather than consent: how vulnerable are they to our ability to poke fun at things on the Internet? It’s hard to take Bill O’Reilly seriously after seeing what’s been done with the “You Can’t Explain That” Advice Animal. Charlie Chaplin’s “Great Dictator” film was considered a powerful political statement which was banned in the UK because they thought it would anger Hitler. As @EthanZ tweeted, laughing at dictators defuses their power, whether it’s Bill O’Reilly or Hitler.

Memes online sometimes feel like they have endless lives. But as soon as memes turn political and affect people’s real lives, does that change?

In World of Warcraft, one guild held a wake for one of their members who had passed away physically, from a stroke. While they were holding their wake, members from a rival guild, Serenity Now, came in and killed them all. Jonathan takes a humming poll to find out whether the audience thinks this is unethical– the volume is about the same both ways.

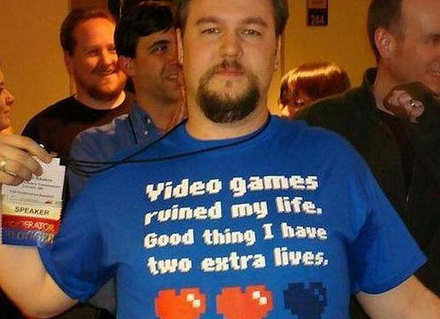

Are memes just a moment that will get replaced? Or is this kind of thing here to stay, or will the participants eventually move on, as with chewing tobacco? Should we put away, as St. Paul encourages us, “childish things?” Or should we, like CS Lewis, put away the fear of being considered childish? Jonathan shows us a t-shirt which reads “Videogames ruined my life. Good thing I have two extra lives.”

We talk about this ironically, but it’s really a serious, empowering statement. Once you accept your role, you can do amazing things. How do we deploy this force? The most countercultural way to deploy this force is against the un-funny cynicism of our mainstream institutions.

We always think the world is coming apart, but “this time Charlie Brown,” says Jonathan, “I think it might be happening.” When we look at our institutions, we see such deeply embedded cynicism that even individual members of these institutions, which are systems, don’t feel like they can escape them. If you’re CEO of FOX News, it’s not clear that you can do anything to change things. Instead, In such an environment, the subversive move is represented by things like the Reddit sub board for random acts of kindness.

Jonathan reveals that he and his girlfriend stood in line for the joyless photo with the Star Trek: The Next Generation cast, with most of the cast members looking stone-faced, with the exception of a few goofy-faced figures such as Wil Wheaton. Jonathan asserts that it is those people—people who own who they are—that will make all the difference on the Web.