“We are new into your thing. We have never been there before; we never wanted to go before until some one of your people, Bill Bunge, whether you want him or not, was telling us about geography and what it could do for us. He showed that geography could be meaningful and it could be useful to our thing. We did not believe him. Then he brought out maps and we still did not believe him. ‘What in the hell is a mountain doing in Detroit?’ That is what we thought about it, all those funny little things geographers do.

Out of all the stuff they were saying to us, we wondered how we could take a little bit out of all that ‘bull’ and make it useful.”

– Gwendolyn Warren, Remarks at the Conference on the Geography of the Future, Bayfield, Ontario, October 18, 1970, as cited in Field Notes III

Geography is often defined as the study of the earth’s surface as the home of man. But the view from which men’s home?

– Dr. Bill Bunge, Society for Human Exploration, Field Notes I

About the Detroit Geographic Expedition

The Detroit Geographic Expedition was the first expedition mounted by the Society for Human Exploration. The goal was to join academic geographers with “folk geographers” (Bungee’s term for people who did not have formal training in geographic methods) and members of the African American community to use geography to create “oughtness maps” – maps of how things are and maps of how things ought to be. The Expedition’s main concern was using geography for social justice and, specifically in Detroit, addressing racial injustice. As Dr. William Bunge wrote in the expedition’s first publication, Field Notes I, “Afterall, it is not the function of geographers to merely map the earth, but to change it.”

Principal players in the Detroit Geographic Expedition included Dr. Bunge and Gwendolyn Warren, an 18-year-old black female community leader and high school pushout who was the past president of the Infernos, a teen club in Detroit’s Fitzgerald neighborhood. Warren had previously led numerous community actions including school walk-outs and protests. Dr. Bunge was an academic geographer of note, having written a well-respected text in the early 60’s entitled “Theoretical Geography”. However Dr. Bunge’s participation in the Civil Rights movement and his unorthodox teaching methods (such as bussing his white commuter students to Detroit’s slums to undertake “human exploration”) led to his dismissal from Wayne State University where he was faculty.

The Detroit Geographic Expedition was a short-lived but powerful education and research experiment. Their activities included 1) mounting a free university for inner city black students to be trained in geography, urban planning and other subjects and gain college credit, and 2) Together with the students and the community, conducting and publishing research on racial injustice in Detroit.

What issues were they addressing?

The Detroit Geographic Expedition was primarily concerned with mapping and addressing racial inequity in Detroit’s inner core. The expedition was formed not long after the 1967 Detroit Riot which remains one of the most destructive and deadly race riots in U.S. history. Prior to the riot Detroit was generally viewed as a positive role model for integrated communities and black leadership from an urban planning perspective, however African Americans did not feel that enough had changed. In the Kerner Commission’s report on the riots, African Americans identified many areas of discrimination: policing, housing, employment, spatial segregation within the city, mistreatment by merchants, shortage of recreational facilities, poor quality of public education, access to medical services, and “the way the war on poverty operated in Detroit” (Violence in the Model City by Sidney Fine). Field Notes III contains numerous references to and personal accounts of the 1967 Detroit Riot’s inception and the subsequent occupation of the city by the National Guard.

The significance of the Detroit Geographic Expedition

In its short trajectory, the DGEI published three research works, led thirty-one free, college-credit courses for inner-city Black residents, and made a significant contribution to the issue of school decentralization in Detroit. They came up with a model for running a community-controlled extension school to the university that was driven by values and focused on how to make abstract college subjects relevant to communities facing daily challenges to their survival. More than anything, the DGEI with its extensive quantitative and qualitative data collection and its use of highly technical and “legitimate” maps and charts, showed just how unjust a place the city was for its Black residents.

While the program was ultimately unsustainable after the departure of its leaders and the always tenuous relationship with the sponsoring institution, it highlights some key questions for future endeavors. How can communities leverage academic expertise, technical know-how, style of discourse and perceived legitimacy to solve difficult local problems? Issues like racial injustice, illegal school districting, and children’s poor health and well-being are large and abstract but have concrete impacts that community residents feel on a daily basis. Is it only the domain of the professional urban planner or the environmental health expert to solve these issues? The DGEI would answer an emphatic “no”. What was most radical about the DGEI was not the data collection or techniques (though those were extremely advanced for the time) but who was making the maps and the urgency felt by those mapmakers. How can maps get closer to the people who live in them, to whom the lines, shapes and patterns are of the utmost importance?

Project Structure

The Detroit Geographic Expedition focused their attention in two areas that informed each other but which remained distinct for the principals: research and education, with Dr. William Bunge as the Research Director and Gwendolyn Warren as the Administrative Director. As Ronald Horvath, a geography professor at Michigan State who participated in the Expedition, describes in The Detroit Geographical Expedition and Institute Experience (1971), “We considered the distinction between research and education to be fundamental and constantly talked about its educational vs its research arm.”

The educational arm, under the direction of Warren, began operating courses for college credit in the summer of 1969 and continued through the summer of 1970. The number of courses offered each semester varied between one and eleven and the subjects ranged from geography and urban planning to philosophy to natural science. The number of students enrolled started at forty for the first semester and grew to 470 at the peak of operations in Spring 1970. But after the Summer of 1970, when many of the black student leaders had moved to East Lansing to attend Michigan State, no courses ran. While the model of free, community-run education seems radical, Horvath notes that its principles were similar to the concept of rural extension practiced by land grant colleges like Michigan State. The principles of the DGEI were:

-

Open. Everyone is admitted and given a chance. “Innocent until proven guilty”.

-

Free. Students do not pay for their classes.

-

Community Control. The project is run by the community. The community is not an advisory board but is the administration of the project.

-

Case Method. Instruction is “project-oriented” rather than “classroom-oriented”.

-

Tithed Faculty System. Faculty volunteer 10% of their time.

-

Best Campus Facilities. Students don’t get “leftovers” of others’ equipment and facilities.

These principles meant that courses were open to anyone and everyone with the idea being that students could take enough credits to eventually transfer to University of Michigan with sophomore status. But even free courses posed a challenge to many inner-city African American students, “[S]ome came hungry, others couldn’t afford bus fare, one student had been living in a car for five weeks. Learning how to make a clean line, lay a zip-a-tone pattern, or design a map with the right combination of point, area, and line symbols did not seem to be critical knowledge to members of a survival culture.(Horvath)” Boosting morale, articulating relevance and channeling students’ energy towards pragmatic community goals became especially important in the process.

Field Notes II: A Report to the Parents of Detroit on School Decentralization

This energy was made manifest in Field Notes II: School Decentralization (1970) and Field Notes III: The Geography of Children (1971), the second and third research publications by the Detroit Geographic Expedition. Field Notes II, also known as “A Report to the Parents of Detroit on School Decentralization”, came out of the work of two of DGEI’s courses: “Cartography” and “Geographical Aspects of Urban Planning”. The study was initiated at the request of State Senator (and later five-term mayor) Coleman Young and John Watson, Director of the West Central Organization, who approached DGEI for technical assistance in analyzing various school redistricting possibilities that had been put forward by the Board of Education.

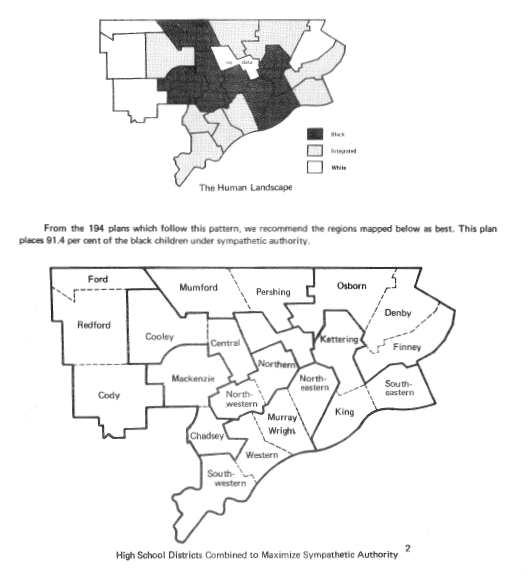

Using extensive maps and charts, Field Notes II evaluated the plans put forward by the Board of Education and found that four of the eight possibilities they proposed were in fact illegal due to the number of students overseen by a district or the way the district was being cut up into discontinuous regions (gerrymandering). Moreover, Field Notes II proposed its own plan for school redistricting and was explicit about its values and criteria for spatial decision-making:

Black children are among the most abused children in America. It is imperative that these most endangered children receive the most protection. (The infant mortality rate of black children in the King High School area on the east side of Detroit is higher than that of San Salvador, a fact that some Americans consider unpatriotic.)…

To meet the primary goal of protecting the most abused children, every possible legal regional combination of Detroit high school districts (over seven thousand) were ranked according to sympathetic authority to the children from most to least. The measure of sympathy used is “the total number of black children under white authority.” A regional school district is defined as being under white authority where a majority of voters voted for white candidates in the mayoral primary.

— Field Notes II, Chapter 1, “Community Control”

In order to maximize sympathy and retain community control over community schools, the DGEI proposed a plan which placed 91.4% of black children under “sympathetic authority”. Their plan followed divided the districts according to the existing racial landscape of the city.

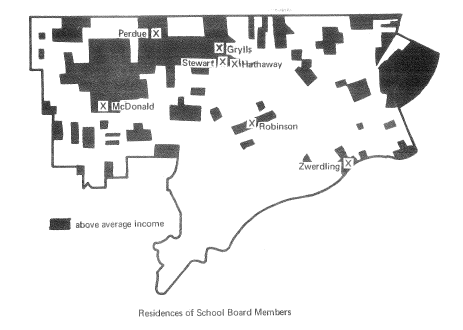

Field Notes II was both extremely creative and highly technical in its mapping and data collection techniques. The report included detailed maps of how the gerrymandering of school districts created “super-majorities” and “super-minorities” (Warren’s words), charted in detail how the Board of Education’s redistricting plans were illegal, mapped the residences of school board members in order to show how their assessment of the plans came from a biased perspective (all were residents of the most affluent regions of Detroit), and collected charts of primary source data such as “pounds of glass on the playground” in order to show the discrepancy between the richest white schools (1 lb of glass at Hampton school playground) and the poorest black schools (364 lbs of glass at Fitzgerald school playground).

Field Notes II was a tour de force which involved community groups, numerous academic geographers doing advanced scientific computing and spatial analysis, and the work of two DGEI classes and their students. The plan was so thorough that the Board of Education was forced to respond to it. The Northwest Community Organization, a black advocacy organization, adopted the DGEI’s plan and fought for its implementation across the city. A separate community group called Parents and Students for Community Control (PSCC) was formed to help disseminate the findings of the report throughout the black community via posters, signs and community meetings. Horvath called this report the peak experience of the Detroit Geographic Expedition when those both internal and external to the organization felt the power of combining community goals and geographic analysis in the service of social justice.

Field Notes III: The Geography of Children

If we must assign a term to our work, we may call it “revolutionary”. For anything to be relevant to Black people, it must be revolutionary. Historically, any change brought about in this nation was brought about through revolution. Education is a means. We must relate it to our people. They must no longer train our people for mere tools in this society. We must make geography relevant. We do make geography Black.

— Yvonne S. Colvard, Editor’s preface, Field Notes IIIThe biggest problems we have taken on are death, hunger, pain, sorrow and frustration in children.

— Gwendolyn Warren, Remarks at the Conference on the Geography of the Future, Bayfield, Ontario, October 18, 1970, as cited in Field Notes III

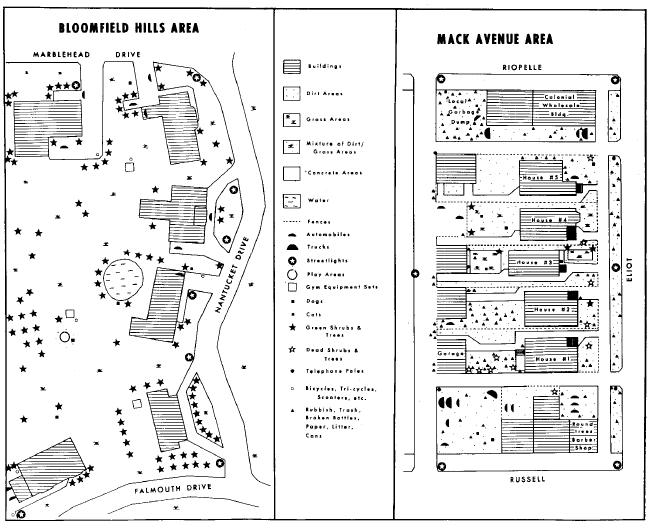

Because its reception is less well-documented, the impact of Field Notes III: The Geography of Children is less clear. In contrast to Field Notes II, Field Notes III contains more qualitative data in the form of personal accounts, ethnographic interviews, and testimonials. Gwendolyn Warren mapped the 21 homes she inhabited growing up and provided harrowing details of rat-infested tenements and their impact on the children in her family. A team of researchers conducted interviews with children on playgrounds in a predominantly white neighborhood and a predominantly black neighborhood, detailed their own observations of the two places, and mapped the visual aspects of the two neighborhoods to characterize the relative dangers and affordances of children’s lives in each.

These reports and observations map very small population samples and spatial areas in great detail and make a compelling case for the spatial inequity of Detroit’s public spaces for children’s play.

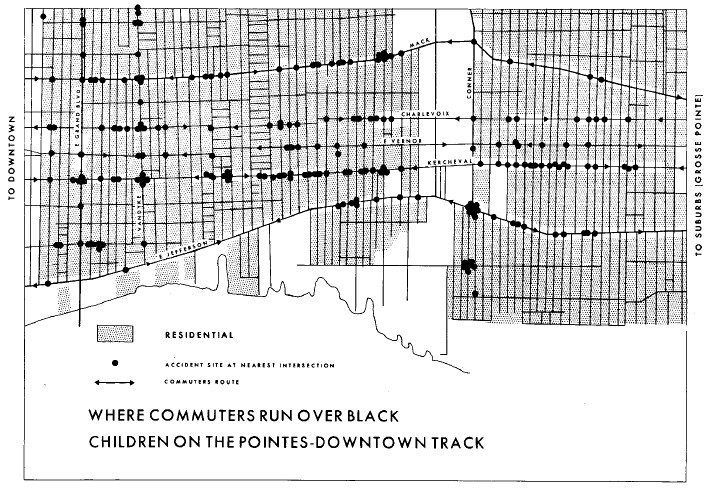

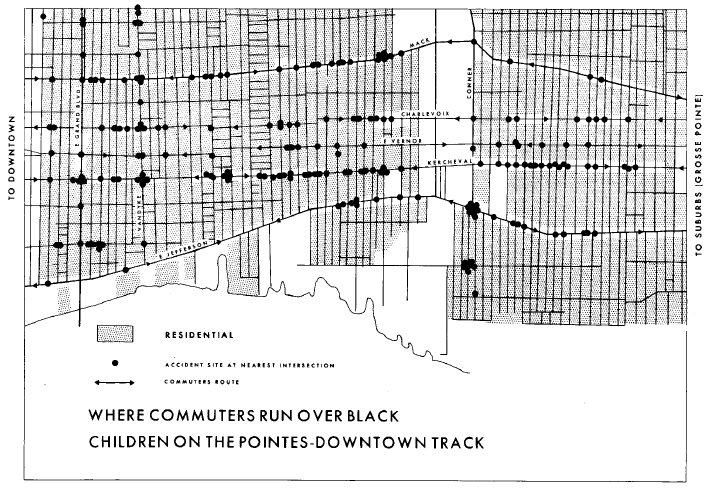

But the most important part of the Field Notes III for Gwendolyn Warren was the research on children’s deaths caused by automobile accidents. She described how a great deal of commuter traffic from the affluent white suburbs to the Downtown area passes through the Black community and poses significant threat to the children. On one single corner alone there were six children killed in six months. Just gathering the data that the community already knew to be true posed a difficult problem. No one was keeping detailed records of these deaths, nor making them publicly available. “Even in the information which the police keep, we couldn’t get that information. We had to use political people in order to use them as a means of getting information from the police department in order to find out exactly what time, where, how and who killed that child. (Warren, p. 12)”

This research culminated in the map entitled, provocatively, “Where Commuters Run Over Black Children on the Pointes-Downtown Track”.

As Warren points out in her analysis, the fact that the map establishes a pattern proves that the children’s deaths are not isolated incidents but rather indicative that the spatial and racial injustice of the city leads to the bodily harm of the most vulnerable members of its lower classes. Denis Wood, a geography scholar who has written about the map in various publications, is definitive, “Any Detroiter would have known that these commuters were white and on their way between work downtown and home in the exclusive Pointes communities to the east. That is, this is a map of where white people, as they rush to and from work, run over black children. That is, it is a map of where white adults kill black kids. It is a map of racist infanticide, a racial child-murder map. (Maps and Protest article)”

In her subsequent analysis, Warren uses this map as a jumping off point to discuss spatial justice more generally for the Black community. For example, most African-Americans work in the factories which are situated several hours from their community so they leave for work at 3 or 4AM because the buses only run once an hour. Those coming from the black community who do have cars are unable to get on the expressway between the hours of 3-5pm due to the timing of the stoplights. She uses these examples and others to unequivocally demonstrate that Detroit’s urban planning and transportation is inadequate and unjust for the Black community and calls for the DGEI to establish “Black planning” for the city of Detroit.

The End of the DGEI

Long before the publication of Field Notes III, the Detroit Geographic Expedition’s relationship with its main funder, Michigan State University, had started to deteriorate. Horvath traces the beginning of the decline of the program to the relocation of the black student leaders to East Lansing in the winter of 1970. Gwendolyn Warren, Robert Ward, Beverly Edwards and Dwight Ferguson enrolled in full-time classes there while at the same time trying to still lead the education arm of the DGEI. The distance between the sponsor institution, the community leaders and the community complicated matters significantly, but the main source of tension was MSU’s refusal to alter the fee structure for the administrative overhead of offering the courses. The DGEI had free facilities, teachers, and administration on the community side but could not afford to pay these costs. The relationship between the DGEI and MSU deteriorated. At a final meeting of the community leaders with the MSU administration, the university presented numerous conditions for the continued operation of the program that included offering it through continuing education and disallowing tithed faculty. Gwendolyn Warren declined to accept these terms and the relationship, and financial support for the DGEI, was effectively terminated.

Further and future expeditions

A postscript by Robert Colenutt to Horvath’s paper on the DGEI describes expeditions undertaken in the summer of 1971 and briefly states that further expeditions are planned. William Bunge wrote about twelve expeditions that took place under the Toronto Geographical Expedition beginning in 1973. Some of these “field guides” were later published in his book with Ronald Bordessa “The Canadian Alternative: Survival, Expeditions and Urban Change: Geographical Monograph No. 2″. There was also a Canadian-American Geographic Expedition which Bunge wrote about in Second Call: The Society for Human Exploration: Field Notes 5 (Canadian-American Geographical Expedition, October 1977). Denis Wood acknowledges Bunge’s first call for the Society for Human Exploration as directly inspiration to his work with children in Puerto Rico (with Ingrid Wood, “Kids and Space in the Highlands of Puerto Rico,” The Geographical Review 96(2), April 2006, pp. 229-258) and to his recently published book “Everything Sings: Maps for a Narrative Atlas” in which he and his students spent twenty years mapping his neighborhood of Boylan Heights in Raleigh, NC. Wood has also made a case for the DGEI as laying some of the groundwork for the Public Participatory GIS mapping projects that came later where academics collaborate with community groups to achieve specific goals using mapping technologies that are normally reserved for specialists.

In recent years, a collaborative group including the SpaceTime Research Collective at the CUNY graduate center, the Public Science Project (CUNY), Cindi Katz (CUNY), and Tara Mack (Education for Liberation Network) are starting a program called “NYC Geographic Expedition and Institute: Liberation education for geographic inquiry”. While public details remain to be released, the project cites the DGEI as its inspiration.

Related Resources:

AMC livestream of Research as Rebellion, the case of the Detroit Geographic Expedition: http://talk.alliedmedia.org/es/node/7109, and notes: http://new.livestream.com/accounts/853564/ResearchRebellion

Wood D, Krygier J. 2009. Maps and Protest. In Kitchin R, Thrift N (eds) International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, Volume 1, pp. 436–441. Oxford: Elsevier