Activists, theorists, media makers and researchers are all struggling to understand the relationship between the recent global cycle of protests and the new media ecology. This panel takes a look at how civic action moves between online and offline spaces, with attention to the SOPA/PIPA battles, Justice for Trayvon Martin, and DREAM Activism.

Panelists:

Sasha Costanza-Chock (@schock) (moderator), Assistant Professor of Civic Media, MIT Comparative Media Studies; Co-Principal Investigator, Center for Civic Media

Jamilah King (@jamilahking), Colorlines

Hal Roberts, Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University

Hal Roberts is a fellow at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University. He has been the lead researcher for Berkman Center reports on Internet surveillance, filtering circumvention, and distributed denial of service attacks against independent media. He is the technical lead on the Media Cloud project, a text aggregation and analysis tool for studying online media created at the Berkman Center. He has worked on the technical side of many social technology projects at the Berkman Center, including H2O, Weblogs at Harvard Law, and Global Voices Online.

Renata Teodoro, Student Immigrant Movement leadership team in 2008 after getting involved in the in-state tuition campaign. Renata quickly took responsibility for organizing fundraising events, implementing new strategies to focus on the strengths of members. She joined the SIM staff in 2009 to focus on resource development and fundraising. In 2010, Renata became part of national movement for the Dream Act through the United We Dream Network. She was part of the leadership that planned and implemented national strategy.

Holmes Wilson, (@fightfortheftr) Fight for the Future

Miro, Open Congress, and Amara (formerly known as Universal Subtitles) and ran online campaigns for the Free Software Foundation (FSF).

Sasha introduces this panel titled In Real Life plus ReTweeting For The Win. He is a professor of Civic Media studies at the Media Lab and Comparative Media Studies (CMS) at MIT where they strive to build tools to create a more engaged public with access to information. CMS brings together people from various fields, from historians to tech people, to help create powerful social movements and civic actors. The people on this panel are from various organizations who work towards civic movement.

Jamilah King on the Trayvon Martin shooting and its aftermath

Jamilah begins by talking about the Trayvon Martin story. Trayvon was a 17-year-old black teenager that was gunned down in Florida. The guy who shot him was questioned by the police but was not criminally charged. This injustice became a national story, and she isinterested in how this happened and what lessons we can apply to other cases. A similar story of Oscar Grant went viral by a video, but this is not how the Trayvon’s story viral.

The Trayvon story spread first through the community that was affected by it and then through social media. The story was compelling because it was larger than just one person; everyone could relate to pieces of the story, whether having a relative that experienced something similar, witnessing a criminal act that never received justice, or just being a part of a community that deals with violence on a daily basis. People started openly talking about the black community and gun violence in Florida. It brought people together in solidarity by giving people the means to share their grief collectively online. This story is a great example of how community activism spawned a media activism story.

Sasha asks Jamilah to describe a couple of the social media strategies that people used as part of the campaign.

Jamilah talks about The Million Hoodie March, organized through social media, which gave everyone a chance to participate in a show of solidarity. People, from kids to grandparents, posted pictures of themselves dressed in a hoodie. [Hoodies were significant because Trayvon was killed while wearing a hoodie, and it helped battle the mediated perception that black males in hoodies are generally criminals.] Well-known black columnists covered this story in great detail. Trayvon’s parents also went on various shows to tell their son’s story.

Hal Roberts on SOPA/PIPA

One of Hal’s projects, as part of the Berkman Center, looked at how people link to stories as a sign of activism. The current example shows data about SOPA and PIPA. SOPA and PIPA only came into the public light through community participation in an online firestorm. His project creates infographics that show how many people link to sites that had information of SOPA/PIPA/COICA. Initially, most of the link activity went to eff.org, govtrack.us, and . In May 2011, PIPA went to a congressional committee, and suddenly two specific sites judiciary.house.gov and wyden.senate.gov received large amounts of link traffic. Senator Wyden’s website had activity because he tried to stop the movement of PIPA.

In November 2011, SOPA was introduced, and the infographic changes to show American Censorship (created by Holmes, panelist) and Wikipedia dominating the link activity. American Censorship, an activist site, becomes the dominant node that people are linking to. In December, Techdirt dominates the graph. Other sites, including Reddit, also show up as they are promoting the boycott of websites like Godaddy. Another site, Fight for the Future (also created by Holmes), is prominently linked.

In January 2012, interest in SOPA and PIPA peaks as Wikipedia promotes an internet blackout. Wikipedia now becomes more than just a source of information but also an activist website themselves as they help organize the boycott. ACTA, the European version of SOPA gains ground in February 2012.

Hal then shows a beautiful infographic of the entire map of nodes and links for SOPA. The colors are site categories, like general activist sites or sites specifically dedicated to SOPA information. It is particularly interesting to see the various kinds of media that were involved and their role in the spread of information. Mainstream media and blogs, oddly enough, were mainly in the background as they linked to other sites but people are not linking back to them for sources of information. The nodes of electronic advocacy organizations, on the other hand, are much more centrally located in the map.

SOPA eventually got shelved, and Hal thinks that this was due to the large number of calls that resulted from the activism. As an example of how big this became, Hal’s dad asked him in December “What is this SOPA thing?” which showed that people who are not necessarily plugged into Techdirt had heard of SOPA through all the dialogue.

Sasha: You bring up an interesting question: so how does this link to real world relationships?

Renata Teodoro on the DREAM Act and the Student Immigrant Movement

Renata has been in the US as an undocumented immigrant from Brazil since the age of six and has kept connected with the DREAM Act movement through the internet. In college, immigration officials found her family, detained her parents, and threatened to arrest her and her siblings. The rest of her family is now back in Brazil, but she managed to stay. When she found the Student Immigrant Movement’s Facebook page, which hosts videos of undocumented immigrant students telling their stories, she immediately contacted the SIM office and is now working for them directly. Back then, SIM did not talk to the press directly without pseudonyms in order to protect the students. In 2010, the push for the DREAM Act brought people from around the country together for a common cause. They were tired of being anonymous and wanted to tell their own stories with their own names. They organized a month of action where they “came out” as undocumented immigrants, sharing their names with media and on Facebook. Renata found that by telling their own stories, it gave them control over the way they were portrayed in the media.

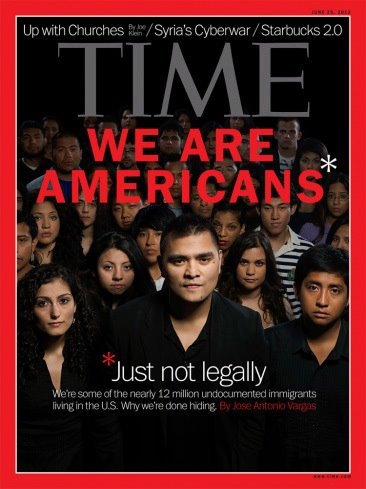

At end of 2010, the Dream Act failed to pass by a five votes in the Senate, which was a devastating loss. Their next plan was to get support from President Obama. They used local ethnic media to get people angry and motivated about the situation of undocumented immigrants. Finally, the day after the Time magazine article titled “We are Americans, just not legal”, Obama announced administration relief to “dreamers”.

Sasha comments on the innovative way dreamers have managed to hook up with ethnic media to get visibility. They have been using social media to livestream activism before Occupy made it cool.

Holmes Wilson on SOPA/PIPA/CISPA activist strategies

Holmes created Fight for the Future, which is an online activist organization for tech policy. The internet has provided this amazing way for people to improve their lives and express themselves, but this newfound power is threatening the status quo. Thus the internet is under attack.

Last October, Congress considered a bill that would make it illegal to post or stream copyrighted material online. This would threaten the very way some people became famous. For example, Justin Bieber got started by singing cover songs, which under this bill, would be considered copyright infringement. Project Free Bieber described how, if SOPA passed, Justin Bieber could be put in jail. Fortunately for Fight for the Future, Justin Bieber was on their side, and when asked about it on a radioshow, he came out fully against the bill. Bieber said, “people need to be free to sing songs”.

SOPA was far worse than PIPA, and Holmes realized that if this bill goes down how it always does, we (the people) will lose. He started American Censorship, promoting websites to go dark for a day in November 2011 to show how the internet would be threatened by SOPA. “SOPA is censorship” was their slogan, and they provided websites the tools to allow people to go directly to supporting and calling their congressman about SOPA.

One key thing they wanted to emphasize is that Congress did not see this as some Internet fluke. They scheduled numerous real life meetings with legislators, and the names of those legislators that ignored them went on Reddit, causing backlash that only the internet community could generate. They also created another site: sopastrike.org.

Sasha asks how we can learn from these success stories and apply these lessons to other struggles? Can the culture of the Internet be used to only win battles of the Internet or can we take lessons from here and apply it to other non-tech areas?

Holmes responds that while we see that an issue like the Internet can create a large tent, we saw the Arab Spring example as well. He thinks that it can be a big tent for lots of issues.

Sasha asks how we use the tools and processes that were described by Holmes and apply them to the DREAM Act?

Renata says that they use the internet to their advantage, but it doesn’t replace the day-to-day, ground work in the community. They realize that they can use the internet to facilitate and augment their work.

Sasha asks if they are thinking about other ways to gather data that can help social movements? “Twitter is the drosophila of social media”. Perhaps we use Twitter because it is easy and has an open API. But how do we capture those conversations over Thanksgiving dinner that can provide a fuller picture?

Hal does not know the best way we can do that. One of the reasons they are doing SOPA is that it worked. It is a pretty unique case in a lot of ways. The internet can be used for politics in lots of ways but other realms don’t have this ready set of actors that can pop in. The other core differentiator about SOPA is that it was totally non-partisan.

Sasha asks about how we can frame and contextualize these stories that occur regularly but aren’t necessarily broadcast as widely as the Trayvon story.

Jamilah emphasizes that social change takes time, and we all need to remember that. The Trayvon case was a compelling story as it was an innocent kid killed by a man who wasn’t prosecuted. We need more stories like this, more stories that matter and hits home with people’s nerves.

Roger Macdonald of the Internet Archive asks how we should prepare to participate and what are the lessons learned from these activism stories.

Holmes says that we want to formalize the miracle of using us as the megaphone of SOPA and somehow apply these to other issues. An example is internetdefensely.org. Not enough people spending time and energy for activism, and in this day and age, the amount of impact can be enormous.

Erhardt Graeff asks about the design process for generalizable action tools.

Laura Kurgan of the Spatial Information Lab at Columbia notes that this panel was really about the intersection of physical and virtual space and how we might think about physical space supporting online activism. The Occupy Movement, for example, made the mistake of fetishizing physical space and Zuccotti Park. But we need to think about how the city can support online activism.

Thank you to the Civic Media live blog team for help on this post!