This is part 2 in a series on a public art project to create a space for dialogue between a concerned community and the owners of a dilapidated Cambridge property. Bigger picture in part 1.

I was enamored with the weight of postcards: How does the sender’s selection of a design suggest something personal? A postcard has more weight than a petition signature and gives flexibility to write a lot or a little, to illustrate concepts and/or capture them in words. It is a dynamic physical artifact.

I had read Karen Klinger’s Cambridge Eyesore series, and it was clear that Cantabrigians noticed these rundown lots. Conversation continues to swirl within the community, but how does the conversation flow back out—beyond the city councilors to the decision-making owners?

Saul Tannenbaum, a citizen journalist and proud Cantabrigian, heard my pitch. Development is more complicated in Cambridge than visualizing community desire for change. A property could be family-owned, and there could be disagreements about what to do with it. Saul wasn’t optimistic that the postcards would persuade the owners to sell, but he suggested Vail Court as a place to start and connected me to Heather, a resident near Vail Court.

Heather and I built on each other’s excitement. She had been trying to get the process moving on Vail Court for a while, and even if the postcards didn’t move the owners, any input was better than none. She helped flesh out the idea. We talked about iterations of the projects to involve passersby and neighbors. We dreamt of a block party—an abandonment birthday party—that would bring people together even if the owners didn’t respond. And to send photos of that party as postcards.

Just a week to the first iteration, I spoke with the Cambridge Community Development Department. They had seen Candy Chang’s creative approach, I Wish This Was, to spark conversation within the community around dilapidated facades in New Orleans. Since then, the department had been thinking about how to engage more citizens around urban planning. CCDD was more worried about whether nearby residents would perceive the postcards as a call-to-arms and expect owners to act (and positively). Despite their reservations, CCDD encouraged me to move forward, echoing that more inputs are always better.

I froze.

Up to this point, my professor had described “Postmarked” as a gesture. We have fundamentally different understandings of what a gesture is: He wanted to see suggestions on banners or wallpaper around a building. The spectacle would be affective. Meanwhile, I wanted to involve people in the process so they would be invested. CCDD seemed to be echoing my professor. Even though I made my expectations clear (give the owners a sense of the lived experience around Vail Court—if they wanted to respond, there would be a place), what if the gesture (the community production, the process, the involvement) overshadowed the expectation? I confronted whether the project could be disempowering, whether I would be abusing people’s attention.

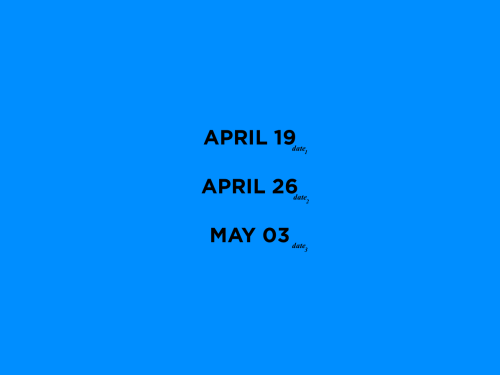

I struggled for a few weeks, pushing back the iteration dates. I talked to Heather. Finally, I realized that to see what I was doing as an abuse, especially if I’m clear about the expectations, is to accord no agency to participants. That sort of thinking meant that people were just cogs for a wheel, the assembly line for along a production process.

So I moved forward. I wrote a letter to nearby neighbors to let them know what was going on. Many people were just happy to see something stirring, even though they did not have high expectations for a change to the property. Neighbors talked to me for 10-20 minutes about what it was like to live near Vail Court, only to write a few sentences on the postcards. Waiting friends picked wildflowers growing around the chain-link fence, and passersby and neighbors chatted about the owners.

A common question, especially from passersby, was shouldn’t the City lead any organizing effort to communicate with the owners? They had done so before, and traces of Vail Court are visible in City Council minutes. They have convened resident advisory committees around Central Square development. But for me, what was particularly striking about this question was it came back to inputs: The city had and could continue to make appeals to the Vail Court owners. But to have multiple people and groups chiming in—most of all the people who experience Vail Court everyday—only adds to the strength of their voice.