Michael Kupperman, author of Mark Twain’s Autobiography 1910-2010, is a writer of what Ethan likes to call “civic fiction.” For more portrayls of civic fiction, Ethan is a fan of Benjamen Walker, who hosts Too Much Information on WFMU. It’s one of the more unusual shows you will ever listen to on the Internet. It’s hard to figure out, according to Ethan, if it’s an interview, a serious news piece, or storytelling that blurs the lines of reality.

Ethan hands over to Ben who begins by introducing Michael and noting that some of the best storytelling being done today is in comics. Michael’s work has appeared in The New Yorker and Screw. His cartoon, Snake ‘n’ Bacon’s Cartoon Cabaret was published in 2000 and is now featured on Cartoon Network.

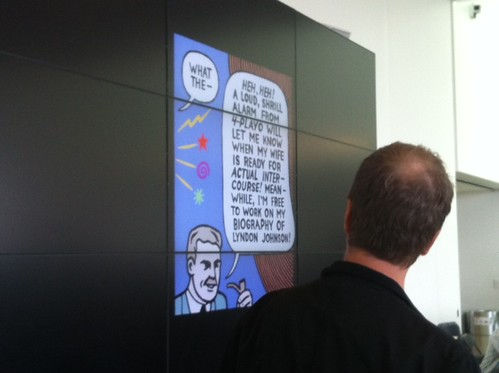

Michael begins his presentation by pointing out that he likes reading his comics to audiences. Comic book in hand, he read from it as he advanced his slideshow. He immediately jumped into an illustrated version of his talk—a hilarious and bizarre set of vignettes which force us to consider whether or not comics can be serious literature. We open with two cowboys arguing over this exact topic. They begin a fist fight, complete with Batman style “POW!” “BAM!” effect bubbles. Next, a story from “4-playo, the amazing foreplay robot.” Then Pagus: Jesus’ half-brother.

Finally, we meet our heroes: Twain and Einstein in “So Boldly We Dare.” They blast off into space to get rid of an asteroid on its way to Earth. The two are a rather entertaining pair, bickering as they take chainsaws and machine guns to the rock. But—oh no—ghosts!

Before our literary science duo can handle them, however, an advert: A set of discount but disappointing products from “Ben’s Warehouse of Cursed Savings”.

Back to Einstein and Twain. After asking the ghosts to leave (following an adventure into the basement of the space shuttle), they head out to the rock and find a floating alien head: “attention foolish humans!” he yells. Turns out, however, the alien is a baby. The science-lit duo is taken by it. Before they can tend to it, they must take care of the task at hand: Einstein sets the bomb timer—”yahoooooooo! Pow!”

The ship heads back to Earth—”attention NASA, we’re coming in hot and I need a place to park this baby.”

Meanwhile, in LA…Tony Scott is finishing his latest film. But here comes the space shuttle!

And that’s the end. I think. I hope. He sings “Don’t stop!” by Fleetwood Mac to the slide of the credits.

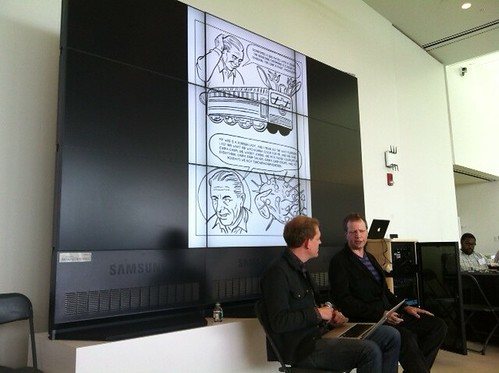

Finally, Benjamen and Michael sit down for some Q&A. And this liveblogger is grateful.

Benjamen starts by quoting Michael’s publisher: “all the great cartoonists today are individualists.” They are all good. We tend to group cartoonists into a movement, but it really is a wonderful collection of individual stylists. What kind of comics are you doing?

M: Um, well, I am going for the laughs. And I’m using dream logic for storytelling. There’s a lot of deep diffusing of expectations. When you build up a dream or story, there’s a lot going on.

B: There’s an interplay between surrealism and humor. You found a formula early on.

M: Not sure it’s a formula. That would make it easier. It’s investigating contradictions that strike me as amusing. This could go in a different direction. Deconstructing narrative tropes is how I’d call it.

B: At the end of the day, you’re focused on humor. “Einstein and Twain” was in many directions, but at the end of the day, the driving force of the narrative is the humor.

photo care of @FromCarl

M: That comes first to me. Art and design are there to carry the joke.

B: We’ve been talking a lot about data visualization at this conference. It seems that in a way, I’d love to get a little deeper into that. Focusing on how you visualize the humor, maybe even going back to the story we saw. Are you making it up as you go along?

M: Kind of. You see high points. You have to build to that humor. Sometimes there’s just enough for three panels—I like to keep it short, keep the audience wanting more. It’s kind of—there can be a central idea I need to do it.

B: Do you feel that—what are the things you’ve learned over 10 years with this interplay? Do you feel you get more comfortable with things getting weird? How do you focus it all towards a punchline?

M: I’ve been doing performances a fair amount: those help me learn where the audience reacts strongest. Like you, I watch a lot of British humor. I also grew up in England. They do a lot of that—changing the idiom in mid-flow. Changing the narrative confines. It’s all geared towards a short attention span.

B: It seems that there is a collection of jokes in your work. When you add everything up together, there’s a stronger humor narrative that is consistently more than just a bunch of punchlines.

M: I’m trying to do that. I think I’ve gotten better at constructing longer and longer permutations of these jokes. When I started, the longest strip was a few pages. The last issue had a Quincy parody which went 18 pages—it was an Inception/Quincy parody: dreams to dreams. Inception to completion.

B: How do you finding the story in a strip like we just saw?

M: In that one, I was trying to develop it as an animation first. It was one of the many ways the material was used. I had this material and I just keep going back and reshaping it. There are lots of ways it could have gone. I script everything in advance. I don’t improvise on the page. That turns into disaster nine times out of ten otherwise. I need to be efficient and keep the material coming out.

B: [To the audience] Michael is on Twitter—he’s one of my favorite people that I follow. It seems that’s worked well for you. Was that something you embraced right away?

M: I thought I’d hate it, really. I despise Facebook. It’s such a horrible experience. On Twitter, I was pushed to get on by some Brit comedian friends of mine. It’s democratic if you’re doing it right. I enjoy the interplay. I enjoy meeting people online—that part of it. There’s a certain call and response thing you get. In England, I’ve been asked to take place in a celebrity auction—a reputation built on Twitter…

B: One of the things for this crowd—there are a lot of journalists—a lot of the funding is based around innovations for the future of journalism. It’s similar in the comics industry—the decimation of publishing, and other similar issues. You work in animation, you’ve produced comics for cell phones…can we end with some of the innovations in the comic space you’ve seen or working towards?

M: I’m pushing my publisher to get into digital publishing. It’s the only way that they are going to survive. My publisher survived because they did Peanuts—which keeps the company afloat. We’re midway now, there need to be new digital platforms. You had the idea of publishing a book in progress and people paying installments towards the final product.

B: We’ll have to apply for a Knight News Challenge.

Question from Larry Birnbaum: You mentioned that you like to use comics to deconstruct rhetorical models. Do you think comic books are a good medium for this as opposed to film or movies?

M: In some ways, that’s an ideal purpose. Storytelling in comics doesn’t compete well with narrative film or fiction. As far as deconstructing tropes, you can do it more efficiently and easily in comics in a way that is harder in other media. There is one I did—there’s an Alan Moore series, League of Extraordinary Gentlemen—I did a parody of it: “League of Appropriated Characters” that just jumbles characters together. Audiences are attracted to meaning and signifiers. Comics are an ideal way to address that.

Question from Jonathan Stray: how do you tell Twain and Einstein apart? They looked identical?

M: Slight rounding in the nose in Einstein and his face is slightly rounder. But that’s part of the joke.

B: You have used these characters before, yes?

M: I did this Twain autobiography and last year I realized I should dress up as Twain. So I did that a few times. It was so much fun to do that.

Question from Ethan: you’re having fun with tropes, not just comics but the innocent 1950’s age of comics. The unbelievable ad that you might clip out and send. What are we going to be satirizing in terms of form 50 years from now?

M: What you get from media in the 1950’s is a presumption of order: an expectation that things will work a certain way. There is no presumption of order today. It’s just a jumble.

Question from Chris Abaraham: Is moving to digital something you’re exciting about or scared?

M: Excited. I was initially scared of it. But it’s where things are going.

Chris: You are not afraid to lose tactility of product?

M: Not especially.

B: Most cartoonists are terrified.

M: You have to accept the inevitable if it’s a way to reach an audience.

Question from Rachel Sklar: Recently, there has been a lot of pushback about the depiction of women in pop culture. I know the comic book world is part of that—there is the meme about male superheroes dressed as female, a meme about Scarlett Johansson on Avengers poster. I’m curious about that discussion. I noticed that your heroes are dudes. Is this a discussion that comes up in the comic book community?

M: Constantly. There are so many women in comics—more than when I started. The depiction of women in superhero comics is a constant cause. Most recent is catwoman cover for Catwoman #1—comics have become inbred, so it wasn’t just inappropriately sexual…the anatomy was all wrong. Enormous pushback these days. Lots of fans are asking why this has to be.

B: At the same time, the explosion of female cartoonists has been amazing, especially in this world for independent comics.

M: I did a show with Kate Beaton—who is just sensational. She’s the most popular right now.