Liveblog of the first panel of the conference Civics Education: Why it Matters to Democracy, Society and You at Harvard Law School, April 1, 2013.

Panelists:

- State Senator Richard Moore (Massachusetts State Senator)

- Howard Gardner (Professor, Harvard Graduate School of Education)

- Peter Levine (Professor, Tufts University and Director of CIRCLE)

- Robert Gallucci (President, MacArthur Foundation)

- Romero Brown (Vice President of Program & Youth Development Services, Boys and Girls Club)

- Moderator: Tomiko Brown-Nagin (Professor, Harvard Law School)

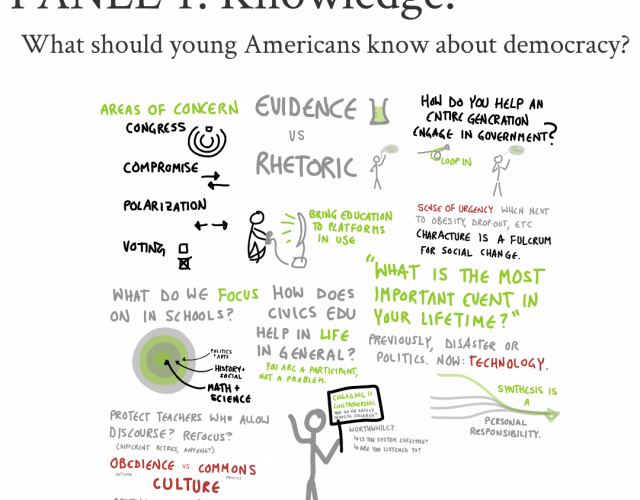

TBN: We are here to talk about what young americans need to know about American democracy: skills, knowledge, and disposition. This conference affirms my childhood interest in civics. First I’ll introduce the speakers and then we’ll put to each speaker, “What do young americans need to know about democracy?” [Introduces State Sen. Richard Moore, who has been a leader in promoting civic education in Massachusetts and the US including chairing a special commission on civic education and learning that recently released the report, ”Renewing the Social Compact.”.]

RM: A couple of things that are not clearly understood by the population as a whole is our foundation in representative democracy. From the local to the federal level, we choose people to represent us as best they are able. Today with movements like the Tea Party, a kind of skepticism or cynicism in government pervades. People have concerns about how they get their voices heard by representatives, and whether they actually agree on something.

I think civics is about understanding some of the concepts of how legislation is decided upon, like working with others that may disagree substantially with you. For the past 65 years, we don’t have a way to get that multiplied — more than just a few students need to understand how this system works. We have a law on the books about what students should know about how government works. However, it’s STEM that gets more attention because civics doesn’t have a standardized test forcing people to teach it. One premise is to teach job skills, but also to be active engaged citizens. How to be an active, engaged citizen; how to find the resources to participate in it: voting or taking the next two steps and serving in government.

TBN: [Introduces Howard Gardner, HGSE Professor, who with colleagues at Project Zero has conducted reflective sessions with young people about ”Good Work”.]

HG: I want to respond to the general topic of democracy, politics, citizenship, and government, and where young people are situated in it. I want to blame the MacArthur Foundation — for better or worse — for leading me to give a very different answer today than I would have 30 years ago. In 9th grade, I had to memorize the Constitution. But nowadays, everyone can call it up on their smart phone. There’s no reason to memorize the Constitution. I don’t think there’s any chance of having a quantum leap with children. Young people find issues of politics to be toxic. When I went to school, there wasn’t a negative reaction to politics. But when you talk about being an activist and civics or democracy, it provokes revulsion. Compromise is something that isn’t happening.

Not only were the media much more limited but also we had a passive relationship with it. Kids are much more interactive with their media today. They can find an app to do what they want to do. Activism is a flash rather than something that takes a long time. It’s like Oscar Wilde’s quote, “The trouble with Marxism is that it takes up too many evenings.”

I have four things to say: 1) Kids need to have stuff they care about. 2) They need to feel efficacious that they can do something about an issue. Our own research shows that privileged kids feel efficacious but don’t have something they want to spend their time on. Whereas, underprivileged kids have the reverse experience, they are very passionate about issues affecting them but have no sense of efficacy. 3) You need knowledge and skills. But kids are not going to be motivated to learn about the branches of government, etc. unless they have something they care about and want to achieve something. This depresses me. They are going to pick up stuff much more helter skelter. Kids think, “To get something done now, these are the things I need to know.” Our own research also suggests that while it’s great to know stuff and be skilled and feel efficacious, at the end of the day if you don’t have a value system that justifies your work, then efficacious isn’t enough (4). I think President Obama was shocked when he reached out to social media and received back that legalization of marijuana was the most important issue.

Kids understand that somewhat at the beginning, but it isn’t until later that they understand it’s not just about whether I’m going to be better off but also will the larger polity be better off.

TBN: [Introduces Peter Levine, Tufts Professor and Director of CIRCLE; he has an upcoming book: We are the ones we are waiting for: The promise of civic renewal in American life.]

PL: I think Howard’s answer is correct. And I want to endorse his answer first. I had a gradual conversion experience over the past 5 years on this issue. There is this prevailing idea that their is a crisis in civics in this country. If you ask American seniors through NAPE, 69% of kids can answer “What is Marbury vs Madison about?” This is because in 40% of states kids take a civics class in which they are tested somehow. Only 8-10 states actually mandate testing on it. But most kids can nail it. If you can get 10s of millions of Americans to answer that question, we aren’t doing so bad. But Howard talked about a broader idea of values and skills and motivation.

The skills and knowledge that kids need are much more robust. They need to analyze a complex public policy issue with others they disagree with. The gold standard for me would be if they can do this analysis as good as Congress (or better than Congress does it now). Kids are doing better than the Naturalization/Citizenship exam. We need these kids to support our government and representative democracy for the next 50 years and for that they need to know more than Marbury vs. Madison.

TBN: [Introduces Robert Gallucci, President of MacArthur Foundation, who has a career in government and foreign service.]

RG: I like that strategy of saying I agree with Howard. Everything I say is add-on. I come at this from a different angle. I come at it from a public policy perspective. For a period at MacArthur, we had a portfolio I called “Saving the Republic,” now it’s the Democracy Project. I found little dissent on the argument that our system isn’t working very well: health policy, criminal justice, energy, etc. We have a sinking feeling that our political process isn’t grappling with them effectively. We are also struggling with philosophically with the loss of the concept of compromise as an essential element in our political system. There is a polarization of politics that everyone recognizes, including gerrymandering, with media magnifying that polarization.

There has also been an attack on voting to tackle a nonexistent problem of fraud. One of the solutions is to expand the number of Americans who are voting, ensuring access to the polls, which Obama addressed in his State of the Union. But does the polity have the capacity to understand complex public policy issues? Do they have the critical skills to assess evidence versus rhetoric? Can they evaluate the quality of the candidates? If they can do that, then the distortions from money in politics is reduced. As our political discourse improves are political processes will improve. If you follow that out you arrive at the question of this panel.

This is a representative government that requires participation and, foremost, informed citizens. They must have civic literacy: issues, quality of candidates, self-interest and common interest, sense of fairness, and a willingness to compromise to gain consensus necessary for action. Citizens need to understand the system of government, i.e. the Constitution, and that’s a good start. Cases and examples are better. A really good discussion of slavery, the moves important to the civil war and the 16th amendment is a better way to go. A discussion around DOMA might be an excellent opportunity right now.

I think internet-based involvement is an excellent medium. But if we do that we will only achieve what Ethan Zuckerman calls thin civics. We need to influence people to get involved in social movements. They need to understand about the power of people: Causes magnified by technology. At MacArthur, we also see an opportunity for open government. For me the bottom line is a critical citizenry. This depends on a solid education: pre-K through 12th grade. They must have that basis for the civic learning to stick, and that’s in a good public education.

TBN: [Introduces Romero Brown, from the Boys & Girls Club of America, who has devoted his career to at-risk youth.]

RB: I want to say what the professor said really hit home for me, because it represents how we at the Boys & Girls Club approach this. Understanding government and how to access it is something we haven’t spent a lot of energy on. The kids in the areas we serve are dealing with a lot of issues and don’t really know how to affect change in those communities. How do we help a generation become more effective?

Well, we are trying to meet them where they are, understanding how it affects their lives. First, bringing service to a higher level. Research says kids who are involved in service reduce risky behaviors and do better in schools. Then we bring in civic knowledge, understand the guiding principles for American citizens: Constitution and Bill of Rights, and understanding key legislation and cases. Contemporary conversation that cites Brown vs Board, etc. resonates with them and makes them feel more involved. Last, what is their role in this system? This brings service in, and we use service learning to have kids involved in strategic engagement on issues and also through the lens of tolerance. Kids need to get used to having positive discourse with each other, or there is a problem as minorities will be the majority in this country in the next few years.

It’s not just the online component but the activity that happens in the club. When they take an idea from a concept to seeing what it takes to get something accepted legislatively, it brings what they see on the television to reality for them. Marrying action at the local, state, and federal level with their knowledge of the system, we hope we will get them to the level of social innovation coming up with solutions we may have never dreamed of. The first step though is just getting them involved.

Our biggest challenge is really around urgency. We focus on good character, lifestyles, and academic success. We look at bad grades or obesity and we react immediately, saying we need to work on that. So we’ve merged this civics lack — which doesn’t have the same urgency — with the character ideal. If we don’t make some kind of intervention now, we aren’t going to have a populace that guide us to be better than we are today. We need positive citizens willing to help a guy on the street.

TBN: How do we promote an agenda of civic education now, when public opinion about our federal government are at historic lows? When I was a student I was very into civics education and the Constitution. That interest occurred when I was growing up in the deep south in the 1970s. I was among the first students to attend desegregated schools. There was a reason to read the constitution.

RM: We don’t value civic educators the same way we value math and science teachers. That sends a signal that it’s not the most important subject to learn. David McCullough says teaching isn’t valued, and social studies in particular isn’t valued. It’s not part of the high stakes testing. [Reference HG’s research:] Some students are interested in things relevant to them and others who know how to get things done. Teachers would be the right people to bring those two sides together. The Generation Citizen model is an ideal for that can happen in the classroom. Few schools have teachers that would put the extra effort in.

We need to take a look at the landscape for what message we are sending to students about the value of this topic. One of the reasons Romney vetoed the commission on civic education was because he was nervous about integrating politics into the school setting. It’s the vanilla-ing of the education; no one wants to do anything risky. How do we get those discussions into a public schools without it being a threat to anyone is going to be a difficult chore. I spent the last few years thinking about how to get people involved in their own healthcare, which is a struggle. How are they going to get involved in their government if they aren’t willing to get involved in their own health?

PL: I think two things are going on. 1) There is a groundswell of people feeling the government is unproductive; I think that’s a hook for us to prepare the next generation to be better. 2) Schools are also in the bullseye; we are more likely to be concerned when students are talking about contemporary issues in schools. How do we support teachers to start that conversation?

HG: What happens when there’s a problem in the school or surrounding community? Can the school as a whole have a conversation about this? Can the school mobilize to do something when there is something to do? Too many homes are dysfunctional. How schools handle things is important. Obedience Culture here is terrible — where people are slapped into obeying. This is versus a Commons Culture in which people are willing to come forward and take responsibility for something. I want a kind of conscience in a school. As long as someone is doing okay on the obedience measures, no one is going to complain about discussing issues in the school gym.

RG: The thing that kids care about plus what they can do… when have I seen this on a large scale? I don’t think I’ve seen something comparable to when I was growing up in the 1960s with the Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam War, both passion and efficacy behind kids getting involved in those issues. It seems to me that if we surveyed issues now, maybe they don’t rise to the same level.

We study framing at MacArthur because we think that is going to make us more successful in getting our work out there on issues like climate change. I can imagine climate change framed in a way that encourages both young and old to get involved with the issues. It seems that there are other public policy issues like that right now, which people want access to and will not be satisfied with the failure of the political processes. [There is disengagement.] I feel things might get a little worse before they get better in terms of engagement.

RB: This focus on testing is hurting us. A more project-based learning approach might prepare kids to react to issues as they come up. Is there a way we can better advocate for how youth receive information, to make that a bigger part of the experience, or bringing partners into the school to facilitate that?

TBN: Can you explain a little more what you mean by project-based learning?

RB: Project-based learning is where kids get a concept or idea and are asked to put together a project around it. If the the issue is DOMA, they need to research, have conversations, know pros/cons, have a debate, see what the community norms are, etc.. It teaches kids through learning a different way. It’s a much deeper way of engagement. They internalize much more and can use it later. [TBN: They own the issue.] Yeah, and they tend to act on it over a longer time because it was fostered during their formative years, like in elementary school.

TBN: [To the rest of the panel] More thoughts about how to teach civics at this fraught moment?

RM: Kids need to get access to the tools to get things done, and how to implement. I think kids can do a lot of role-playing in these cases but it doesn’t get adopted. If kids can get more understanding of the pros and cons that can make sense to a larger population… I think kids should be thinking not just about what to do but how that message will be received. We often short-change kids opinions because their young. Also, we have to write our civic information [government documents] at a 5th grade level, so maybe we are speaking about a larger group here.

HG: I want to offer a surprising piece of data from Arthur Levine: This is the first generation in 100 years that when you ask them what the most important thing that happened to them, it’s not about some political event or disaster, it’s about technology. Moreover, technology is only something that has occurred after they were born. Knowing this is the most defining characteristic of a generation… it’s not intuitive.

Idea: let’s take an issue that kids care about and let’s present to them 3–4 ways to tackle that issue and let them discuss and talk about which is the best approach. And then throw it back to them and ask, can you think of a better way? I look forward to 5 o’clock Friday on NPR to the conversation between David Brooks and EJ Dionne, because it’s civil even when they disagree. I have no idea if this generation would find that interesting. I think we need to know more about the kinds of ways that kids would find compelling for addressing contemporary issues. I have run these reflective discussions with Harvard students for the past few years, and it’s been about dating and number of hours of sleep. Rather than assuming we know which are best the issues and ways of discussing them, ask the youth to do that.

TBN: Need to be less top-down about this.

PL: Many of my colleagues have complained about high stakes testing. But HG gave the example of real activities that kids can do with each other. And we could do them online so that we can keep track of those conversations. At the same moment we have elaborate online education technology we still have 19th century technology for testing — pencil and paper. The next generation of evaluation should be built into activities, we could learn much more about what kids know, but also make things much more inspiring and interactive.

TBN: We live in a world today often seen through a practical lens. Kids want to know that subject matter will help them in their college and careers. Will civics help them in these endeavors and how so?

PL: Just like RB was saying in the Boys & Girls Clubs, kids are more motivated to do well and stay in school if they are involved in their communities. When you tell kids they can be part of a solution, they often light up and get motivated. And they are more likely to develop intellectual skills through the process.

RM: Kids like to collect things on their resume in high school: honor society, sports, etc. But we don’t ask them what did they learn from those experiences unless they fail MCAS twice, then the final way to pass is a portfolio to show what they learned. We should probably reverse that and start with the portfolio. We ask doctors to have continuing education, and then they send in the list of courses, but we don’t know what they learned. This is a common problem, where we need to understand what people are actually learning from their experiences.

HG: Nowadays, we try to justify everything instrumentally. That’s not a good thing. If we want to have a national conversation about what kind of society we want to have that needs to come from the President. Superficially, if it sounds like it will help beat China it sounds better. The country is currently agreeing on using the Common Core standards. There are two consortia looking at how kids learning will be judged against those core standards. What the country wants is Massachusetts-like performance standards with Mississippi spending levels. What these consortia choose to do with new media could lead us in the right direction. But if we go with the 19th century model, then countries like those in Scandinavia that professionalize good teaching will run away with the century.

[Name missed], Boston University Professor: How do we address issues around religion and diversity in schools?

RG: I am going to rely upon how I address this in my own family. I think that for me, critical thinking is an important part, and the ability to distinguish between evidence and rhetoric. When I think about religion myself, I think about faith-based activity, and I don’t subject my religious beliefs to scientific rigor. So when I approach public policy issues, I think it’s easier to sort out one form the other. Then some of these issues are mitigated when you want to show respect for looking at evolution from both a scientific and religious view.

RM: At Boston College, there is a great conversation going on now around a group that wants to distribute condoms [News Story].

HG: It would be a fantastic teaching moment, because most of the students say they want the condoms but the Catholic hierarchy doesn’t.

Dean Martha Minow: It strikes me there are two fault lines in the discussion. To feel passionate and efficacious, we have to feel respected and that the systems are working. Is citizen education grappling with that? Should it? Second, it’s controversial if you engage in democracy. Schools and teachers and worried about it. If we really want people to engage in it, we need to tackle that. In some places, critical thinking is controversial. Maybe learning to get along with people you disagree with… maybe that should be a centerpiece of this civics project?

RB: I think tolerance should be integrated into the educational process. If people are talking to each other we’ll never move on these issues we care about. We value each other and build value in each other’s opinion. You can’t do that if you don’t meet each other in a framework of respect

RM: I would hope that the way civics is taught would get the public to understand that there are few policies that are black and white. What is going on in many states is that the folks that are willing to come up with answer, unless it’s pure, are dropped, they are unelected. So officials become stiff. We need to teach those skills and civility to the polity.

PL: I think the Dean was right to say that controversy is controversial and needs an active movement supporting it. We need tolerance for controversy.

HG: To facilitate things like this is very difficult too. That’s why Roger Fisher’s Getting to YES has been so successful. We can’t expect that conversations about evolution will be smooth unless we train teachers to handle that.

Charlie White, Boston University: Can citizenship education help careers? We often find ourselves justifying civics for careers. What if we discover that the public really doesn’t want the kind of civic education we are talking about? Is there a way to get opinion leaders to support this issue?

PL: An AEI survey says that other kids should get a civic education, i.e. to behave better. They are not enthusiastic about intellectually challenging civics.

[Name missed]: My concern is around policy issues around civic engagement, that every child should have a standardized exam on civics. What I liked was that civic engagement drives civic learning, so how do we generate policy that makes that happen?

HG: If you asked people what they wanted in education 30 years ago, you wouldn’t hear what we are talking about. The Charlottesville Summit has got us to where we are at now. An unengaged citizenry is bad and then go from there. I’ve been having the same conversation about arts education for many years. And artist-citizen is gaining some traction with the leadership of Damian Woetzel and Yo-Yo Ma, and might be part of the general conversation in the next few years. So we shouldn’t give up.

Nell Breyer, Kennedy Institute: It seems like the distributed way that people are now learning through technology is at odds with what you are describing as the ideal way of teaching civics as an integrated moment. How do you rectify this tension?

HG: That question is too hard. Synthesis is a personal responsibility; you can’t force people to synthesize things. Martha was right; you shouldn’t condemn a small group of people for doing something because that’s the only way things have been done. You can’t legislate putting humpty dumpty together. When RG was talking about 1960s there were inspiring people leading us then.

Lissy Medvedow, Discovering Justice: I’m picking up on what Dean Minow was saying about disagreeing without being disagreeable. My organization starts in first grade, we are trying to inculcate kids from a young age in what it means to be a good citizen. I’m worried about the focus on STEM. How can help you support kids learning at a young age?

RB: That’s been our [Boys & Girls Club’s] biggest challenge for the work on healthy lifestyles starting at a young age. I think aligning it more closely with academics can help. It track outcomes more. Looking at outcomes that resonate with funders might better equip your organization with the dollars you need.

RM: Obviously the funding is key, and we need to find out the right message to have folks understand that this is important: disagreeing without being disagreeable. When Congress used to agree on things, they funded the Department of Education to have conversations on the role of civics in schools. I don’t think they had money after only 3 years to do those. I would be interested to see if we could even get that conversation around funding those things started nowadays.