[This liveblog was written by J. Nathan Mathias and edited by Amy Johnson and Gabi Schaffzin]

Yesterday we saw the incredible innovations of six of this year’s Knight Challenge winners. As if that weren’t enough, we then had the rapid-fire presentations of projects from students at MIT’s Center for Civic Media. This provocative session discusses more broadly some of the directions news and civic media may take in the future. Expect the unexpected.

The panel consists of Larry Birnbaum of Northwestern University/Knight News Innovation Lab; Kate Darling, research specialist at the MIT Media Lab; Greg Marra of Google; Ben Moskowitz of Mozilla; Dan Schultz graduate student at the MIT Media Lab and Knight-Mozilla Fellow; and Alberto Ibargüen, president and CEO of the Knight Foundation. Lorrie LeJeune, program director of MIT’s Center for Civic Media, moderates.

Let’s shake the tree. Lorrie introduces the session by encouraging us to turn everything on its head. How will the things we’ve been talking about impact us in three years? Five years? Unlike the other panels, they built this final one around people rather than topics.

Lorrie shows us a Monty Python sketch, describing the two characters as John Bracken (on the right) and Ethan Zuckerman (on the left):

Speaking on intellectual property issues and pornography, Kate starts by clarifying that, contrary to the misconceptions of some of her academic colleagues, the porn industry is not some sort of underground Mafia. Rather, it is a very large, very profitable business sector.

The online porn business is estimated to be worth billions of dollars. We don’t have exact numbers because people don’t want to research the industry. But the porn industry has been on the forefront of technology and new media ever since the proliferation of the paper book. They have driven standards with regard to VHS, the Blu-Ray/HD debate, secure online payment systems, and high-def streaming. And they’re always first.

Why is that? People want their product, of course, and there’s a healthy competition in the industry. But the real reason is that they’ve never been in a position to spend much resources trying to fight change or hold on to outdated business models. It would be a waste, for they have never gotten the same support from the legal system and policymakers as other industries. As a result, they have always had to adapt to the new reality or die.

In the early days of the ‘net, small firms didn’t have the ability to fight piracy. But neither did the larger firms. In the 90s, when Playboy realised that people were sharing their images online, they were elated—free marketing. So they watermarked the images, tracked who shared them. When they found the people who were sharing the images, they contacted them and offered to pay them for links back to their content. This approach strengthened their brand while bringing in people who were willing to pay.

What are people willing to pay for? People expect to get most online content for free. Still, people do go to brands they trust and pay when they 1. need something urgently, 2. need something specific, or 3. simply need the convenience of finding exactly what they want. As a result, the porn industry has developed sites which lead consumers from free content to the purchases they want, simply and easily. While a porn consumer’s sense of purchasing urgency may not translate exactly to other industries, Kate thinks the principle of convenience holds.

The adult industry has also experimented with interactive experiences: games, live chat, and choose your own adventure. They are at a disadvantage on mobile, since they have been banned from Apple phones; regardless, they’re still expanding into mobile and cloud services.

Recently, the porn industry has been consolidating. Companies are starting to own the whole vertical, from production to youtube-like sites used to market their brands. Kate says that the companies that moved early have been very successful.

Overall, Kate argues that the porn industry’s focus on innovation has been much more successful than the lawsuit-and-lobbying strategy of the music and film industries. How does the demand for porn compare to other information industries? The demand for porn is fairly recession proof.

Larry Birnbaum

Next, computer scientist

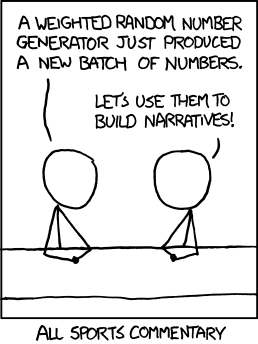

Larry illustrates this by talking about a machine he designed to tell stories. He shows us an XKCD comic about a machine that writes sports stories—and the company that he started to do just that: Narrative Science (Wired: Can an Algorithm Write a Better News Story Than a Human Reporter?).

Narrative Science covers every Big Ten womens’ softball team story recap. Many publishers use the company’s content; their program is now the most prolific author of women’s collegiate softball stories.

He shows us an app for parents which invites them to enter sports data so that the system will write an article about the game. Over the last year, they published 300,000 Little League stories. They expect to cover 2 million this season. But the real money is in finance, and they write Forbes quarterly earnings recap stories.

Larry encourages us to think about text as an alternative form of data visualisation. He shows us an automatically written article on how Newt Gingrich was faring in social media. The machine monitored Twitter and constructed a summary based on social analytics.

To automate writing, we need to have a model for the editorial process. He talks about editorial models as “first-class media objects,” computational models which can be shared and passed between systems. Making them first-class objects also makes them open to scrutiny, debate, and modification.

One example is the Babl prototype designed by one of his students. Babl follows topics online, for example Apple’s World Wide Developer’s conference. Babl will show what people are saying about the topic in social media, based on a curatorial model that someone—anyone who has the app—has created. Individuals can publish and share their own curatorial models. Larry shows us a model he created for the #CivicMedia conference, a combination of searches, Twitter accounts, and hashtags. After creating a curatorial model, the model is tweeted to a hashtag that anyone can follow.

Is Larry doing data visualization with prose? He responds that text can provide a guided tour of data, but the best stories come from some knowledge that the system has—for example, identifying if a player in a game made a heroic individual effort.

Can algorithmic stories scale in quality, or just in speed? At the moment things are somewhat limited, but we’re just starting. Larry imagines defining a set of computational narrative frames similar to the narratives used by journalists to write stories.

Kate asks what it means to assign copyright to machine and encourages Larry to use a Creative Commons license. The company has never considered Creative Commons. The investors set the condition of creating patent applications for every idea, with the goal of building proprietary technology to produce proprietary media content.

Dan talks about automated storytelling in videogames. He points out that Diablo 3 has the concept of a grind— automated parts of the game that don’t forward the storyline. To what extent, he asks, will algorithms cover the grind of writing articles, and where do we need humans?

Greg Marra

Greg Marra, from Google, talks to us about social bots and the idea of autonomous software agents. Ever since social news websites, there have been initiatives to game those sites. In the upcoming Mexican presidential election, one candidate’s campaign has created thousands of Twitter accounts to criticise other candidates. We may think that we’re educated consumers, who know that not everything we read is fact, but we still get swayed.

Greg shows us two inspirational quotes, one which encourages us to focus on the beautiful life, and the other which is a spiritual encouragement. One is from @horse_ebooks, and the other the Dalai Llama.

Next, Greg offers to show us how to make our own socialbots. A good one identifies its targets, figures out how to infiltrate them, and then exploits that infiltration. He shows a graph of two unconnected clusters on Twitter with high network density. How do you knit these together? Pick a few people in this network, identify things they like, and send tweets about these things. But how do you implement this plan? First, read their Twitter accounts and find the keywords they like (he uses an example focusing on tweets about happiness, holidays, and time). Then, find tweets from other people about those topics and copy them. He shows us an example from one of the bots. Even though everything is copied, it’s very easy for our mind to fill in details, to construct narrative and make conclusions about the person. This works across language.

Greg talks about the Web Ecology Project’s social robot competition. If your robot got followers, you got points, if your robot carried out a conversation, you got more points, and if you got found out, you lost lots of points. One approach used within this competition was to send requests to Mechanical Turk for tweet information. Other tools enabled an individual to supervise hundreds of thousands of robots. The software also offered a way to cash in on the trust you have developed—programming your bots to tweet about the same thing at the same time.

These social bots show us that we can no longer assume that what’s recent in social media is necessarily reputable.

People are already doing this, including the US Government’s Operation Earnest Voice initiative. It’s hard to detect this kind of stuff. The Mexican election campaign was noticed because all of the accounts tweeted at once. But bots designed to increase Klout scores are much harder to notice.

Larry imagines positive uses for this technology. He talks about a project which takes tweets from a political candidate, finds the most appropriate response tweeted from another candidate, and pairs them up.

Question: Has Greg ever pulled the plug on a bot for ethical reasons? He tells the story of @trackgirl, a bot which always tweeted about marathon training. And then one day, the bot mentioned that it had sprained its knee. People sent @ replies and DMs with with sympathy.

Kate asks how long it will be until Twitter is entirely comprised of companies trying to do covert product placements. Greg responds, “I thought that’s why we have Twitter.”

Ben Moskowitz

Next, Ben talks to us about drones. Drone research tends to focus on autonomous drones, however today Ben will talk to us about networked flying robots, whether they’re autonomous or controlled by humans.

Drone journalism is a spreading meme, driven by discussions about US drone policy. But for right now, let’s talk instead about what will happen when people everywhere have access to them. He shows us an image from a shopping mall. People are not freaking out.

Ben gives us a tour of drone journalism from $299 and up. He shows us the Parrot AR Drone. For $299, you can get a flying machine which can be controlled from an iPad or mobile phone. People at Occupy attempted to use these to document protests from the sky. They failed because the drones are not designed to take much wind, they have limited battery power, and they easily fly out of range.

The $500 to $1500 price range includes products like the QuoteGate,” when someone made a very slight remix of a quotation in the Irish Times by an Irish politician. People didn’t notice the remix and tweeted the fabricated quote. Other people saw the quote and went back to the original article, triggering complaints that the full quote had been removed. The IT team of the Irish Times had to prove that they weren’t hacked. It took time to untangle, but Dan thinks the resulting conversation is one we need to have more often.